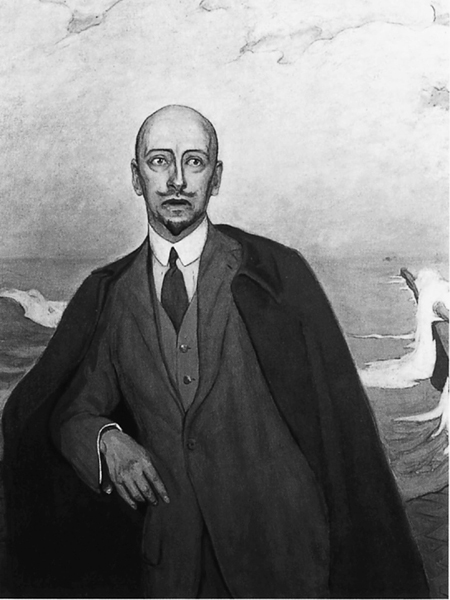

DAnnunzioa portrait painted in 1910 by his lover, Romaine Brooks

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2013 by Lucy Hughes-Hallett

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company. Originally published in Great Britain as The Pike by Fourth Estate, a division of HarperCollinsPublishers, London.

eBook ISBN: 9780385349703

Hardcover ISBN: 9780307263933

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hughes-Hallett, Lucy.

Gabriele dAnnunzio : poet, seducer, and preacher of war / by Lucy Hughes-Hallett.First edition.

pages cm

Published simultaneously in Canada.

A Borzoi bookTitle page verso.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-307-26393-3

1. DAnnunzio, Gabriele, 18631938. 2. DAnnunzio, Gabriele, 18631938Political and social views. 3. NationalistsItalyBiography. 4. Poets, Italian20th centuryBiography. 5. FascismItalyHistory20th century. 6. MilitarismItalyHistory 20th century. 7. ItalyPolitics and government19141945. 8. Politics and literatureItaly19141918Territorial questionsCroatiaRijeka. I. Title.

DG 575. A 6 H 84 2013

858.809dc23

[B] 2012033943

Cover photograph of Gabriele dAnnunzio, 1917

Alinari/The Image Works

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

Map copyright John Gilkes

v3.1_r2

For Lettice and Mary, with love

CONTENTS

I

ECCE HOMO

II

STREAMS

III

WAR AND PEACE

The Pike

I N SEPTEMBER 1919, Gabriele dAnnunziopoet, aviator, nationalist demagogue, war heroassumed the leadership of 186 mutineers from the Italian army. Driving in a bright red Fiat so full of flowers that one observer mistook it for a hearse (dAnnunzio adored flowers), he led them in a march on the harbour city of Fiume in Croatia, part of the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire over whose dismemberment the victorious Allied leaders were deliberating in Paris. An army representing the Allies lay across the route. Its orders from the Allied high command were clear: to stop dAnnunzio, if necessary by shooting him dead. That army, though, was Italian, and a high proportion of its members sympathised with what dAnnunzio was doing. One after another its officers disregarded instructions. It was, dAnnunzio told a journalist later, almost comical the way the regular troops gave way, or deserted to follow in his train.

By the time he reached Fiume his following was some 2,000 strong. He was welcomed into the city by rapturous crowds who had been up all night waiting for him. An officer passing through the main square in the early hours of that morning saw it filled with women wearing evening dress and carrying guns, an image that nicely encapsulates the nature of the placeat once a phantasmagorical party and a battlegroundduring the fifteen months that dAnnunzio would hold Fiume as its Duce and dictator, in defiance of all the Allied powers.

Gabriele dAnnunzio was a man of vehement, but incoherent, political views. As the greatest Italian poet, in his own (and many others) estimation, since Dante, he was il Vate, the national bard. He was a spokesman for the irredentist movement, whose enthusiasts wished to regain all those territories which had once been, or so they claimed, Italian, and which had been left irredenti (unredeemed) when Italians liberated themselves from foreign rulers in the previous century. His overt aim in coming to Fiume had been to make the place, which had a large Italian population, a part of Italy. Within days of his arrival it became evident this aim was unrealistic. Rather than admitting defeat, dAnnunzio enlarged his vision of what his little fiefdom might be. It was not just a patch of disputed territory. He announced that he was creating there a model city-state, one so politically innovative and so culturally brilliant that the whole drab, war-exhausted world would be dazzled by it. He called his Fiume a searchlight radiant in the midst of an ocean of abjection. It was a sacred fire whose sparks, flying on the wind, would set the world alight. It was the City of the Holocaust.

The place became a political laboratory. Socialists, anarchists, syndicalists, and some of those who had begun, earlier that year, to call themselves fascists, congregated there. Representatives of Sinn Fin and of nationalist groups from India and Egypt arrived, discreetly followed by British agents. Then there were the groups whose homeland was not of this earth: the Union of Free Spirits Tending Towards Perfection who met under a fig tree in the old town to talk about free love and the abolition of money, and YOGA, a kind of political-club-cum-street-gang described by one of its members as an Island of the Blest in the infinite sea of history.

DAnnunzian Fiume was a Land of Cockaigne, an extra-legitimate space where normal rules didnt apply. It was also a land of cocaine (fashionably carried in a little gold box in the waistcoat pocket). Deserters and adrenalin-starved war veterans alike sought a refuge there from the dreariness of economic depression and the tedium of peace. Drug dealers and prostitutes followed them into the city: one visitor reported he had never known sex so cheap. So did aristocratic dilettantes, runaway teenagers, poets and poetry lovers from all over the Western world. Fiume in 1919 was as magnetic to an international confraternity of discontented idealists as San Franciscos Haight-Ashbury would be in 1968; but, unlike the hippies, dAnnunzios followers intended to make war as well as love. They formed a combustible mix. Every foreign office in Europe posted agents in Fiume, anxiously watching what dAnnunzio was up to. Journalists crammed the hotels.

DAnnunzio was already a bestselling novelist, a revered poet, and a dramatist whose premieres were attended by royalty and triggered riots. Now he boasted that in Fiume he was making an artwork whose materials were human lives. Fiumes public life was a non-stop street-theatre performance. One observer likened life in the city to an endless fourteenth of July: Songs, dances, rockets, fireworks, speeches. Eloquence! Eloquence! Eloquence!

By the time his occupation of Fiume came to an end, dAnnunzios dream of an ideal society had deteriorated into a nightmare of ethnic conflict and ritualised violence. For over a year it suited none of the great powers to bestir themselves to eject him, but when, eventually, an Italian warship arrived in the harbour and bombarded his headquarters, he capitulated after a five-day fight. But for the duration of his command, Fiume wasprecisely as he had intended it should bethe stage for an extraordinary real-life drama with a cast of thousands and a worldwide audience, one in which some of the darkest themes of the next half-centurys history were announced.