Chris Kraus

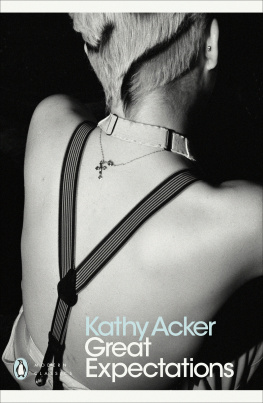

AFTER KATHY ACKER

A Biography

Contents

For Sabina Ott

memories haunt me, increasing frequency and my sense of the obdurate. Time transforms into thing; no wonder myths of afterlife and rebirth proliferatethis is the dubious gift of reliving narratives which may never have existed, but which appear to carry the concrete weight of the world. Memories transform into inert substance, a form of hardness, as one grows distant from them. One is fashioned by the fashioning of them.

Alan Sondheim, autobiog.txt

You realize that the past is just like everything elseits a dream. And its just as much of a fiction as if you were actually writing fiction and we choose to say or choose to remember or cant remember how to remember whatever it was you were trying to remember. It comes out filtered and redefined and has an envelope of fiction to it. Because were all basically fiction.

Rudy Wurlizer, interview by Jonathan Dixon, Vice magazine

TO BEGIN

As the twentieth century fades out

the nineteenth begins

again

it is as if nothing happened

though those who lived it thought

that everything was happening

enough to name a world for & a time

to hold it in your hand

unlimitedthe last delusion

like the perfect mask of death

Jerome Rothenberg, for

Jean-Pierre Faye

Littoral Madness

Like everything in the past, everyone remembers it differently, and some of the people involved hardly remember at all. Were talking about something that happened more than seventeen years ago. But on January 23, 1998, which was a Friday, friends of the late writer Kathy Acker drove from San Francisco to Fort Funston park, about twenty-five minutes away, to scatter her ashes. Shed died two months earlier at an alternative clinic in Tijuana, where she received palliative care for late-stage, metastasized cancer.

The ash scatteringlike the wake at Bob Glcks house on December 13 and the memorial reading at Slims Bar where Michelle Handelman was booed off the stage for no reason she can recalldevolved into a kind of black comedy, the way these things often do. I remember Cookie Mueller at Jackie Curtiss memorial, standing up on the stage of La MaMa halfway through an evening of readings and monologues, blinking back tears as she faced the dark auditorium. She had no speech prepared. I thought this was supposed to be a funeral, she said to the room. Not a variety show. Speaking to Sylvre Lotringer, the artist Steve Brown recalled how the elegantly planned Nembutal suicide of Danceteria emcee Haoui Montaug among a small group of friends ended with a plastic bag over his head. He was a large man, in the late stages of AIDS, and whoever arranged for the pills had underestimated the dose. Before time accelerated, deaths among friends in the art world were like salt to a sting, bringing unresolved feuds to the surface. Now we care less, or are nicer.

Around this time last year, when I started working on what may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker, I imagined beginning the book with the melee at Slims Bar, or at the wake, where a group of friends gathered to transfer her ashes from a box to an urn, or at the scattering. To describe these proceedings would be to stage an establishing shot of a movie that uses a single protagonist to traverse an entire milieu. Although she wrote first-person fiction and gave hundreds of interviews in which she was asked to recite the facts of her life over and over again, these facts are hard to pin down in any literal way. Because in a certain sense, Acker lied all the time. She was rich, she was poor, she was the mother of twins, shed been a stripper for years, a guest editor of Film Comment magazine at the age of fourteen, a graduate student of Herbert Marcuses. She lied when it was clearly beneficial to her, and she lied even when it was not. Perceptive readers of Ackers work have observed that the lies werent literal lies, but more a system of magical thought. As Dodie Bellamy notes in her essay Digging Through Kathy Ackers Stuff: Over and over, Acker tells the same tale: the mother is pregnant with the daughter, and the father leaves. The mother blames the daughter and tries to abort her. The daughters body survives, but not her unified self . Is it true? Does it matter? Acker liberates libido from Freuds repressed underworld. But then again, didnt she do what all writers must do? Create a position from which to write?

Ackers life was a fable, and to describe the confusion and love and conflicting agendas behind these memorials would be to sketch an apocryphal allegory of an artistic life in the late twentieth century. It is girls from which stories begin, she wrote in her last notebook. And like other lives, but unlike most fables, it was created through means both within and beyond her control.

* * *

By the time Acker died, at age fifty, shed known thousands of people. Since her divorce from her second husband, Peter Gordon, in 1979, shed had no long-term partner. Shed lived, at different times in her life, in San Diego, San Francisco, New York, and London, a half-conscious rotation between cities familiar to her. I think she was just always trying to find her community, the technology writer R. U. Sirius told me last year at a Mill Valley caf. Michael Bracewell, whod known her in London during the mid-1980s, concurred. Shed bought, then abandoned an apartment in Brighton. Her friend Gary Pulsifer doubts she ever spent a night there. Estranged from her remaining immediate family, shed known poets and bikers, leather dykes, tattooists, philosophers, astrologers, renowned artists and writers, bodybuilders, psychics, promoters, and editors, and shed slept with a great number of them. In London, she played chess with Salman Rushdie.

Shed lived in San Francisco between 1990 and 1996, teaching a class in New Genres at the Art Institute while trying to find a more stable, tenure-track job anywhere in the U.S. During those years she worked out at a Golds Gym, published two novels, toured constantly, recorded CDs, and added an enormous, impressive tattoo across her shoulders and upper back to the series of pictographs already inscribed on her body. Literal madness; images written not just as words on the page, but as pictures on flesh. The tattooan enormous lizardlike fish overlaid with a garland of flowers that morphs into a sleek airborne birdwas done in the style of Ed Hardy and took weeks to complete. Her friend Kathy Brew recalls Acker coming into her office in the Humanities Department after each session and saying, Honey, would you put some cream on my back? After the last session, Brew grabbed her camera and took a much-reproduced photograph of a bare-chested Acker astride her 650cc motorcycle. We were just playing around. It felt like two girls playing dress-up, or something. Brew was newly divorced, and during those years the two hung out a lot, talking about being single, desire, and intimacy, and then in 94 Brew moved back to New York.

By the time Acker left San Francisco for London in July 96, shed stopped talking to a lot of her former friends in the citys literary worlds and cyberpunk scene. With some, thered been feuds. Others couldnt handle her medical choices and denial of the cancer, which had been diagnosed in April that year. When she returned to San Francisco in September, she was no longer closely in touch with anyone from her old extensive and disparate circles. From a hotel, she called Aline Mare, an old colleague from the Art Institute, and asked for help. Shed known Mare years before in New York, but in San Francisco their friendship had been distant, at best. Mare recalls running into Acker holding court at parties and openings, looking into the middle distance beyond her old friend. Oh cmon, Kathy, I