Copyright by George Leopold 2016. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available at the Library of Congress.

By the end of the 1960s, twelve human beings had traveled to the moon; four had walked on its barren, untouched surface. Eight more American astronauts would reach the lunar highlands in the early 1970s. The American people and NASA had accomplished what they said they would do: land men on the moon by the end of the decade and bring them back. And it was done in front of the entire world. When asked what it all meant a few weeks after his return from the moon in July 1969, Apollo 11 command module pilot Michael Collins put this singular human achievement into perspective: I think it [was] a technical triumph for this country to have said what it was going to do a number of years ago, and then by golly do it just like we said we were going to do.

In the decades since the final US moon landing, most of Americas early astronauts recorded their stories for posterity. In one form or another, these early space pioneers published their memoirs, mostly with the help of professional writers or aerospace journalists who covered their exploits. (Notable exceptions include Collins, undoubtedly the finest writer ever sent into space, and Walter Cunningham, who chronicled the early years of NASA along with his own career as an Apollo astronaut.)

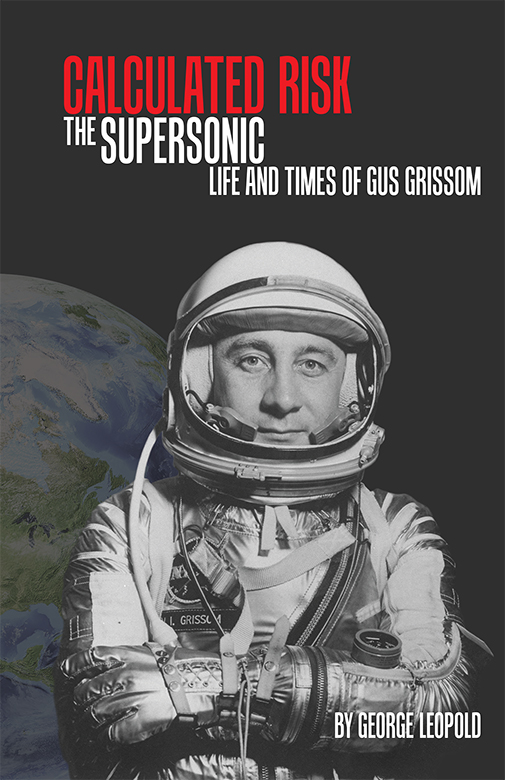

From Shepard to Glenn, Armstrong to Cernan, these men were able to shape the publics perception of these early astronauts lives and careers. While Virgil Ivan Gus Grissom managed to coauthor one book about his role in the Gemini program before his death (completing a draft manuscript weeks before the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967), most of what we know or think about the third human being to fly in space, if we think of him at all, was shaped by press accounts, documentary snippets, and a few interviews given by the press-shy Grissom to trusted newspaper and television reporters. In the early days of the Space Race, inhabited as it was with ultra-competitive men with enormous egos, Gus Grissom was often a footnote.

Aside from a 1968 self-published tribute by the Grissom familys pastor and a 2004 biography that focuses heavily on Grissoms Indiana years, no comprehensive survey exists of this simultaneously simple and complex man, his supersonic life, and his tragic and unnecessary death. This volume is intended to fill that gap in the historical record, to examine the life and career of Gus Grissom, to reconsider his place in the annals of space exploration as well as in the history of the Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Grissom was a Cold Warrior in the truest sense. No geopolitical rivalry better defines this period of human history than the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union for supremacy in space exploration. The first waypoint was a manned lunar landing. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and President John F. Kennedy understood this instinctively. America, Kennedy concluded early in his administration, could not survive if the Soviet Union controlled outer space.

By hanging their hides out on the line, Grissom and his fellow Mercury astronauts became the instruments, the business end, of US Cold War strategy. Grissom was an eager, willing participant, agonizing over every Soviet space spectacular, and then redoubling his own efforts to keep pace and eventually pass the Soviets in a race to the moon.

By the mid-1960s, with planning for lunar missions well under way and technological development moving at a breakneck pace, Grissom had emerged from the pack as the odds-on favorite to be the first human being to walk on the moon. He would focus all of his energies on that goal. He and his family would pay the ultimate price for his unswerving dedication.

The reticent test pilot and astronaut from downstate Indiana was more than willing to do the tedious testing and other unglamorous engineering work required to reach the moon by the end of the 1960s. He was utterly uninterested in tickertape parades and White House ceremonies, unimpressed, as fellow astronaut Wally Schirra later observed, with personal prestige. Gus Grissom did not care. He just wanted to fly. And the best place to go was 238,000 miles from Earth.

Charles Watkinson, former director of Purdue University Press, launched this project. Charles took a chance on a first-time author, ably pointing me in the right direction until his departure to greener pastures (the University of Michigan Press) in 2014. Charles embodies the gentleman and scholar ideal.

Charless successor, Peter Froehlich, has been equally encouraging since taking the reins at Purdue University Press in 2015. Peter and his able staff saw this project through to completion. Special thanks go to editor Katherine Purple, who repeatedly saved me from myself. Editors do the unglamorous work of untangling prose and helping authors tell their stories in ways that are accessible to a broad audience. Beloved American classics such as To Kill a Mockingbird, we have recently discovered, would have been far less appreciated without the steady hand of a wise book editor.

As this project took shape, I was struck by a deep and abiding affection for Gus Grissom. He connected on a visceral level with average Americans in a way the other astronauts, placed as they were on pedestals, could not. Gus was the everyman. Americans rooted for him. Among the reasons were his humble beginnings along with his determination and willingness to size up situations and take risks. Guss youngest brother, Lowell, gives greater meaning to the phrase brotherly love. Lowell has kept the memory of his big brother alive through the decades. He was gracious with his time and straightforward in discussing the meaning of his brothers life and deeds. Gus would be proud of his kid brother.

Few researchers know more about the career of Virgil Grissom than Rick Boos. As a student in the 1960s, Rick corresponded with the astronaut in the heyday of American spaceflight. Those letters from Grissom had a profound effect on Rick, who made it his lifes work to document the astronauts contributions and correct the misconceptions about his career. Rick willingly shared his years of research, particularly the controversial ending of Grissoms Mercury spaceflight and profound tragedy that killed the crew of Apollo 1. Rick and I talked for hours; I have done my level best to accurately convey the results of his extensive research. I am in Ricks debt.

To the present day, we continue to ponder the watershed events of the 1960s, especially the remarkable early days of human spaceflight. The families of the men who challenged the vacuum of space also were key actors in mankinds greatest adventure. Kris Stoever, the erudite daughter of Malcolm Scott Carpenter and coauthor of her fathers memoir,