Jasper Becker - Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine

Here you can read online Jasper Becker - Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1997, publisher: Free Press, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine

- Author:

- Publisher:Free Press

- Genre:

- Year:1997

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Maos Secret Famine

JASPER BECKER

Copyright 1996, 2013 by Jasper Becker All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

First Published in Great Britain by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.

Also published by THE FREE PRESS A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020

This eBook version published by eBookPartnership.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Becker, Jasper.

Hungry ghosts: Maos secret famine / Jasper Becker, p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-684-83457-X

1. FaminesChina. 2. Food supplyChina. 3. Mao, Tse-Tung, 1893-1976. I. Tide. HC430.F3B33 1997 363.80951 09045dc20

96-32803 CIP

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78301-249-7

Print ISBN: 0-684-83457-X

For Ru who supplied me with tea and sympathy

- Victims of the Ukrainian famine of 1932-3 which presaged an even greater disaster in China during the Great Leap Forward

- The massive labour-intensive projects into which peasants all over China were marshalled during the Great Leap Forward

- Propaganda boasting of Chinas miraculous agricultural yields

- Chen Boda and Li Jingquan, two of those responsible for the worst excesses during the Great Leap Forward

- Two provincial Party Secretaries, Zeng Xisheng and Wu Zhifu, under whose leadership millions starved to death in Anhui and Henan

- Evidence of the alleged scientific successes of the Great Leap Forward

- The backyard furnaces, intended to help triple steel output

- The most hated aspect of the communes the communal kitchens which were run as militarized units

- The campaign to exterminate the four pests and the drive to mechanize agriculture produced ingenious solutions but were in the end useless

- 0. In the Great Leap Forwards attempt to master nature, nothing was deemed impossible if the masses were mobilized to perform extraordinary feats of manual labour

- Those who opposed Maos policies were condemned as rightists; those forced to implement his policies were condemned to hard labour

- Party leaders who benefited from the Great Leap Forward: Hua Guofeng, Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang and Kang Sheng

- The Great Leap Forwards chief victim, Marshal Peng Dehuai, whose letter of criticism to Mao led to his condemnation as a rightist

- Two of those who helped to end the famine and thus earned Maos hatred: Liu Shaoqi and Zhang Wentian

- The tenth Panchen Lama and the writer Deng Tuo both dared to speak out during the famine and suffered the consequences of their audacity

- Mao Zedong, architect of the famine

The author and publisher would like to thank David King for permission to reproduce Plates 1 and 16.

One of the most remarkable things about the famine which occurred in China between 1958 and 1962 was that for over twenty years, no one was sure whether it had even taken place. Whatever else the Communists in China might have done, it was widely assumed that they had at least fed their vast population and had ended Chinas seemingly perennial famines. Then, in the mid-1980s, American demographers were able to examine the population statistics which had been released when China launched her open-door policy in 1979. Their conclusion was startling: at least 30 million people had starved to death, far more than anyone, including the most militant critics of the Chinese Communist Party, had ever imagined.

Why, and how, did such a cataclysm take place? Who was to blame? How was it kept secret for so long? And what was life like in the countryside? How did people behave and how did they survive?

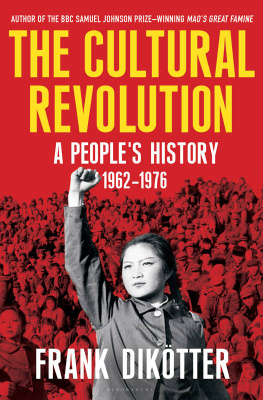

This book is an attempt to seek answers to these questions. Inside China, the famine is rarely mentioned or discussed, and much of the story remains shrouded in secrecy. In the official view, there were merely three years of natural disasters: the real disaster took place later, during the Cultural Revolution, when senior Communist leaders were persecuted. Yet in the last few years, a growing number of Chinese living abroad have written memoirs that shed more light on the subject. It has become clear that the greatest trauma suffered by the Chinese people was indeed the famine, not the Cultural Revolution. However, most of these memoirs are by intellectuals who, during the famine, were either in the cities or in prison camps and so knew little about the fate of the vast majority of the Chinese population the peasants. It was the peasants who were the chief victims of the famine but peasants do not write books, or make films, and rarely have a chance to talk to outsiders. Even those who obtain official permission to carry out research in Chinas countryside are rarely, if ever, allowed to speak freely to peasants. Invariably, local officials have coached the peasant beforehand on what to say and insist on being present at the interview. Often, too, they interrupt to talk on behalf of the peasants who, in any case, may well speak a dialect unintelligible to outsiders.

For those who were in the countryside at the time, the horror of the famine is indelibly imprinted on their memories. As the dissident Wei Jingsheng has written, peasants talk of those days as if they had lived through an apocalypse. Even after three decades, memories are still fresh, as became clear when I started to find people who had then been in the countryside but who were now living outside China. Advertisements placed in the overseas Chinese press in 1994 brought hundreds of responses, ranging from a few scribbled lines to accounts twenty or thirty pages long. I visited some of those who replied, at first in Britain and later in the United States, Hong Kong and eventually Dharamsala in India where I met Tibetans who had fled to the Dalai Lamas place of exile. Then, armed with a clearer picture of what had happened, I travelled around rural areas of Henan, Anhui and Sichuan and talked to older peasants who had survived the famine.

The background to the famine is drawn from the growing body of academic work on Chinese agriculture. I was also fortunate in being able to find written sources to substantiate the cruelties that eyewitnesses had described. The relative freedom allowed to obscure publishing houses in the provinces in recent years has meant that a surprising amount of material about the famine has become available. In addition, Chinese intellectuals who went into exile after 1989 were able to provide a number of official documents about events in Henan and Anhui which offered detailed facts and figures.

Even so, many pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are still missing. Knowledge of events at the highest levels of the Communist Party at key moments is often sketchy, making it difficult to understand clearly why things happened as they did. Much data about death totals is also absent and it is hard to be sure of the reliability of what has come to light. Even today Chinese statistics are rarely coherent, and the central government frequently complains about the regularity with which the lower levels of the administration falsify figures. As Walter Mallory wrote in 1926 of a request for the bottom facts about an earlier famine in China, There is no bottom in China, and no facts. A fuller account of the famine may have to wait until the Partys own archives are open to researchers but this is unlikely to occur so long as those who share responsibility for the famine remain in power. Lord Acton once spoke of the undying penalty which history has the power to inflict on the wrong: it is no surprise that the Communist Party believes its control over the past is the key to its future.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine»

Look at similar books to Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.