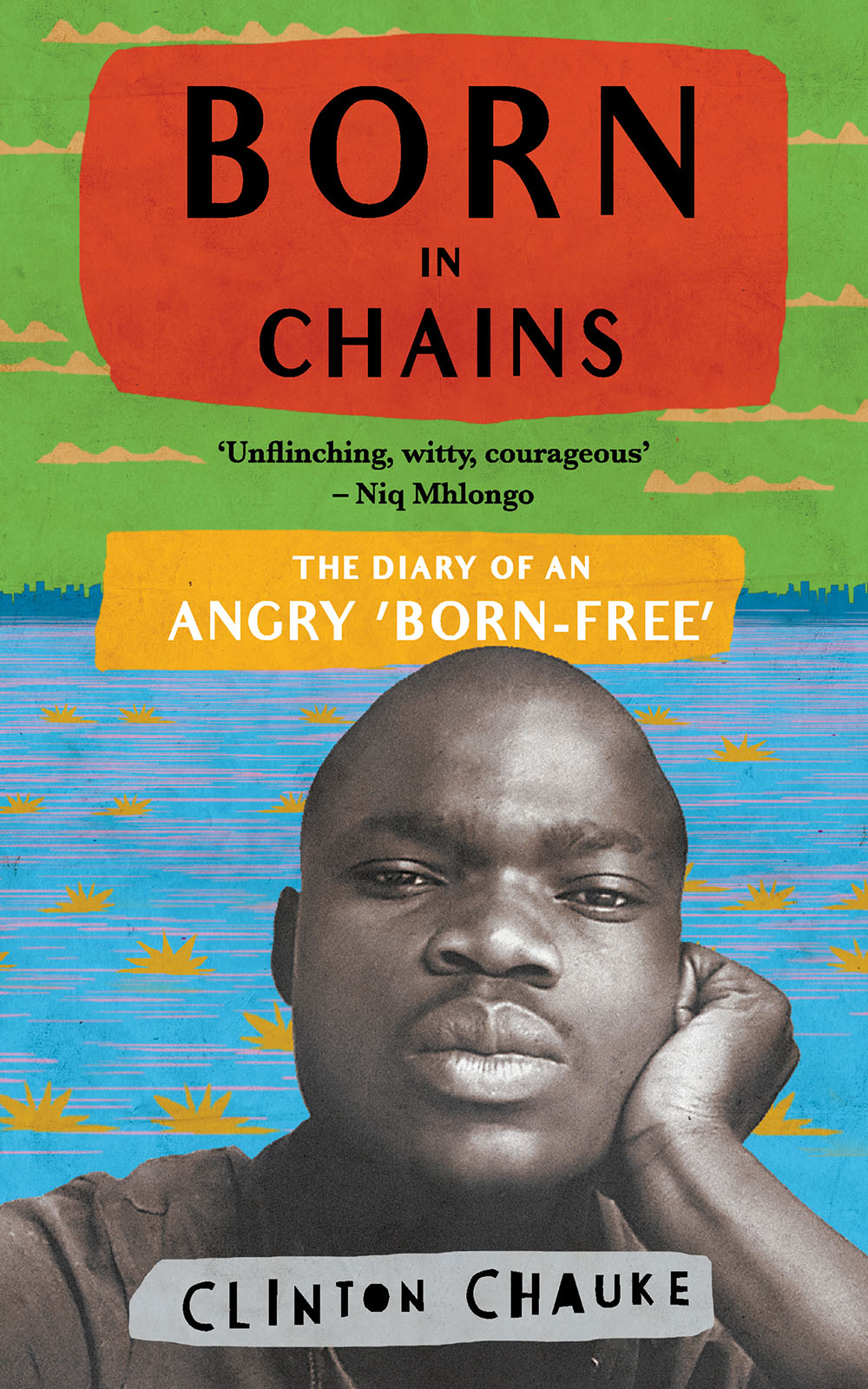

Often, in South Africa, it is the old and accomplished who share their stories. The youth are left to one side. This group of the old and accomplished often comments on the issues concerning the youth, but we hardly hear about these issues from the horses mouth. I have decided to share my story as a young and proud black man living in South Africa. I have decided to share my experiences, and how I see the world, from this perspective. My story is not unique. It is similar to that of a lot of other young people in this country.

My fellow South Africans should read my story because I believe that, in it, we can all see ourselves. Its central message is to reject the born-free label, which many people love to romanticise, forgetting its implications. Overall, I am telling my fellow South Africans, especially those who are young and black, that we are in a war! We are fighting for economic freedom. Politically, we are free, but economically, we are still far behind. I challenge my fellow young people to lift their thoughts, to question everything and to be courageous. After all, that is the essence of being young. To be young means to be idealistic. To be young means to be hyperactive. To be young means to think without limits and never stop questioning the status quo.

In this book, I reflect on the past and critically analyse the present to save the future. Reflecting at the age of twenty-three may be very uncommon indeed, and may seem premature, but history has shown that it is the youth who have the capacity to move societies forward. It is the youth who often see the fractures in an unjust society. I hope you enjoy my story.

Chapter 1

Early life

I was born and bred in one of the poorest corners of South Africa. I am the product of labourers who grew up during the reign of one of the worst racial tyrannies the world has ever seen. The time when race was used to determine who was more, and less, human. The time when being black was like a disease.

Apartheid was the order of the day. Black people were already divided before apartheid was embraced by the government: when the National Party (NP) ascended to power after the countrys general elections in 1948, they capitalised on the divisions that already existed between the countrys different tribes.

When my mother was pregnant with me, South Africa conceived her democracy. It was ushered in by the first multiracial elections, which the African National Congress (ANC) won by a huge margin. The former Robben Island prisoner Nelson Mandela was sworn in as the first black president. Then, South Africa started to get confused.

My paternal grandfather was born during World War I in 1918, the same year that Nelson Mandela was born, far away from the corridors of power in Makrimani (ka-Bueli) village, west of the Rivhubye (Levubu) River in what is now Limpopo province. He would wake up every day dealing with the small matters of rural South Africa, always minding his own business, with his wife Tsatsawani Chauke and their five children in order of birth, Mkhacani, Mbhazima, Mphephu, Mthavini and Jameson Chauke.

They resettled in Bevhula village after they were removed from the west side of Rivhubye, part of what is now called Thohoyanou, the main centre of the Vena region, close to Nanoni, a key water source area. They planted mango, avocado and banana trees at their own home, known as ka-Dumazi.

In 1969, they were forcibly removed, like most Vatsonga, from areas that were to become the Republic of Vena. The Republic of Vena homeland was created as the Vhavena Tribal Authority. Like Transkei, Ciskei and Bophuthatswana, this so-called republic was another way in which the government perpetuated black division and white domination.

The Vhavena gained power and coded Shumela Vena (Work for Vena) into their republics coat of arms. This code symbolised the empowerment of Vhavena, mostly through employment opportunities. Anyone who was not Muvena like my grandparents, who were Vatsonga was not welcome and could not contribute to Shumela Vena . Many Vatsonga who had jobs in Louis Trichardt (now Makhado) were laid off to make way for Vhavena.

The Vhavena code led to serious tribalism against Vatsonga, who felt rejected and excluded. The tension between the two tribes still exists to this day Vatsonga are demanding their own independent municipality in modern South Africa. My grandparents were transported with all their belongings, excluding their livestock, by huge trucks known as GGs (short for Government Garages) in 1969 and resettled on the eastern side of the Levubu River in Malamulele district.

Malamulele was the first district to be built in the former Tsonga homeland of Gazankulu, before the other six districts (Giyani, Nkowankowa, Nwa-Mitwa, Lulekani, Mhala and Hlanganani) were formed, their chief minister being Prof. Hudson William Edison Ntsanwisi.

Not long after they arrived in Bevhula in 1970, my grandmother died in Tshilidzini Hospital, after suffering from respiratory problems. They put her on a stepladder, used as a casket, wrapped her in a blanket, and then buried her in the yard, since there was no cemetery in the village. My father had no real memories of his biological mother, Tsatsawani Chauke. He was mostly raised by his stepmother, Mjaji Chauke, whom my grandfather married after Tsatsawanis death.

When my grandparents arrived in Bevhula in 1969, the area was populated with wild animals such as elephant, lion and springbok. They used to burn firewood to drive the animals away. The European settlers would kill the elephants, wrap them in plastic bags and give them to my grandparents, who were staying in camping tents. They also gave them oranges and apples in an attempt to atone for the evil of removing them from the land they had occupied before. The wild animals remained at large, however, and in many instances they killed people the western fence of the Kruger National Park was still open, being closed only in 1980.

The forced removal of Vatsonga, motivated by the racist laws of the time, disrupted the peaceful existence they had led in Makrimani. It reduced them to poverty and dependency on cheap wage labour in Johannesburg. My grandfather left his home a ya xambila Joni (and went to Johannesburg) to look for a job. He travelled by bicycle for over five hundred kilometres, taking rests in the bushes en route to Johannesburg. Upon arriving in Johannesburg, he stayed in the hostels of Jeppe and worked at a company called Sun Control.

He would visit my illiterate step-grandmother and his children very infrequently.

Unfortunately, he passed away when I was a year old. I am told that I look exactly like him. Everyone who knew him tells me I remind them of the old man. His name was Jackson. He named his son, my father, Jameson. I am told that my father wanted to name me Mackson to keep the rhythm going, but my mother refused.

My maternal grandfather, John JB Baloyi, was born in 1920 in Sibasa, Vena. He later resettled in Potgietersrus (now Mokopane). He went to Johannesburg in 1950 to work as a miner and stayed in a hostel in Dube, Soweto, the township bordering Johannesburgs mining belt in the south.

My grandfather and other migrant workers who stayed in the hostels were later given houses according to their ethnic groups. In 1956, my grandfather got a house in the same township, house number 4185 Masungwini Street, Chiawelo. Chiawelo is a TshiVena word meaning place of rest. It was where Vhavena and Vatsonga were placed, since they had been neighbours in Limpopo. It was known in Xitsonga as Tshiawelo tsha Vhavena na Matshangani (resting place for Vhavena and Vatsonga).