Jo Wheeler

THE HURRICANE GIRLS

The inspirational true story of the women who dared to fly

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE HURRICANE GIRLS

Jo Wheeler is a writer and radio producer who has written books with Battersea Dogs and Cats Home and worked with a 1950s policewoman to write her memoir, Bobby on the Beat. She has also produced numerous historical and arts documentaries for the BBC.

In memory of Dai Evans, 19282017,

who always encouraged me.

Introduction

Since the birth of powered flight there have been women pilots. In 1903, nineteen-year-old American Aida de Acosta became the first woman to fly solo in a motorised airship. Six months later, the Wright brothers made their own historic flight, in the first heavier-than-air plane, and flung open the doors to the golden age of aviation. Women like the American inventor Lillian Todd designed some of the earliest planes, and Raymonde de Laroche, Blanche Scott, Harriet Quimby and others took to the skies.

Hilda Hewlett was the first woman in Britain to get a pilots licence, in 1911. She started and ran the countrys first flying school and set up a company which produced over 800 military aircraft during the First World War. Other women aviators went on to set records, fly solo in ground-breaking long-distance journeys, and make their names in the flying races and daredevil air circuses of the 1920s and 30s. Despite these achievements, prejudice about what constituted womens work meant that flying was a largely male domain, and only a small percentage of women were ever able to break through into commercial aviation. Flying of any kind was restricted to those who could afford the expensive lessons.

By 1939 war was looming in Europe. To guard against the prospect of being outgunned in the sky, a subsidised flying scheme, the Civil Air Guard, was set up in Britain to train both male and female pilots. Not very happy about the prospect of a lot more women capering about in planes, one magazine editor responded sharply: The menace is the woman who thinks that she ought to be flying a high-speed bomber, when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly.

Two years later Flight Captain Winifred Crossley stepped out of a Hawker Hurricane. She had just experienced the kick and whoosh of the fast fighter which the previous summer had blazed its trails across the sky and helped to win the Battle of Britain. In her flying helmet and goggles, she smiled as she greeted the waiting crowd: Its lovely, darlings! A beautiful little aeroplane. She had just made history as the first woman to fly an operational RAF fighter. Two years after that twenty-eight-year old Lettice Curtis became the first woman to fly a four-engined heavy bomber. She was soon flying the Halifax, Stirling and celebrated Avro Lancaster. Measuring nearly 22 metres in length with a wingspan of 30 metres, the aircraft towered over the pilot. But it was no problem for Lettice, or the other women who flew four-engined planes during the war.

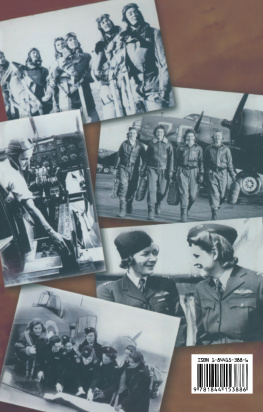

Women were not allowed to join the RAF, but they were allowed to fly with the Air Transport Auxiliary, a civilian organisation which ferried over a hundred different types of aircraft. In everything from open-cockpit biplanes to nifty fighters, cumbersome seaplanes and heavy bombers, they flew without radio, dodging unpredictable weather, barrage balloons and anti-aircraft fire, with only a map, compass and their eyesight to navigate the treacherous wartime skies. During the Second World War, 168 women, along with over 1,000 male pilots, moved over 300,000 aircraft from factories and maintenance units to air force squadrons across the country, and eventually to the Continent, ensuring the Allies had a steady supply of operational planes.

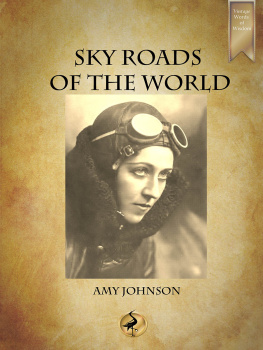

The ATA Girls were celebrated in the press as glamorous heroines of the air, and the war offered them opportunities that would have been unthinkable outside the urgency of conflict. But it could also be tough, gruelling and dangerous work, and not everyone survived. In the winter of 1941 the celebrated pilot Amy Johnson disappeared into the Thames Estuary with a plane she was flying for the ATA. Others fell foul of aircraft malfunctions and accidents, and at least fifteen airwomen lost their lives during the war.

This book tells just a few of the remarkable stories of the wartime women pilots. Thanks to the efforts of their tenacious leader Pauline Gower, who fought tirelessly for her pilots at every turn, they even achieved equal pay, and the ATA became one of the countrys first equal opportunities employers. Being women in what was seen as a mans world had its challenges. But then there was always the prospect of settling into the cockpit of a 350 mph fighter and, just for a moment, leaving the earthly world and all its concerns behind.

1. Learning to Fly

Tensions were high in 1938. Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany and, despite Adolf Hitlers promises to the contrary, an attack on Czechoslovakia was his likely next move. When he made a vitriolic and warmongering speech in Berlin that September many peoples fears were confirmed: war in Europe was coming.

Rosemary Rees had flown to Germany in her own plane many times. She had lots of friends on the Continent and had been flying all over Europe for several years. She was a member of a flying club at the exclusive Heston Aerodrome in London and a regular at the rallies and parties organised by European flying clubs. These were glamorous, champagne-quaffing affairs, where the top aviators of the day mingled over tales of aviation daring. They were hosted in each others towns and cities by mayors and dignitaries. Rosemary was proud of her most treasured possession, a newly developed, sleek, silver monoplane, a Miles Whitney Straight, and she had hand-stitched a massive coat for it to wear in the hangar. It was always the cleanest, shiniest aircraft at every rally.

It wasnt unusual for Rosemary to be in Berlin, because her cousins husband worked at the embassy there. On this occasion, he was jittery.

I think you should take your plane home as quickly as possible. War could be declared very suddenly, he said. It could come at any moment, the way that mans talking, and the first thing theyll do of course is ground all aircraft and not let anyone get any petrol. Itd be awful if you lost the plane. I really think you ought to go home.

The prospect of losing her beloved Whitney persuaded Rosemary to hop straight back in it and head for England.

Neville Chamberlain was keen to avoid another war. In September, he met Adolf Hitler to discuss the terms of a possible peace agreement. After their talks in Munich the Prime Minister landed at Heston Aerodrome and addressed the crowd:

This morning I had another talk with the German Chancellor, Herr Hitler, and here is the paper which bears his name upon it as well as mine, he announced triumphantly, waving the document in the air. We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.

There were cheers and cries of hear, hear from the crowd, but many believed war was still the only option to stop Hitlers advances. Later, outside 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister said: