CONTENTS

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

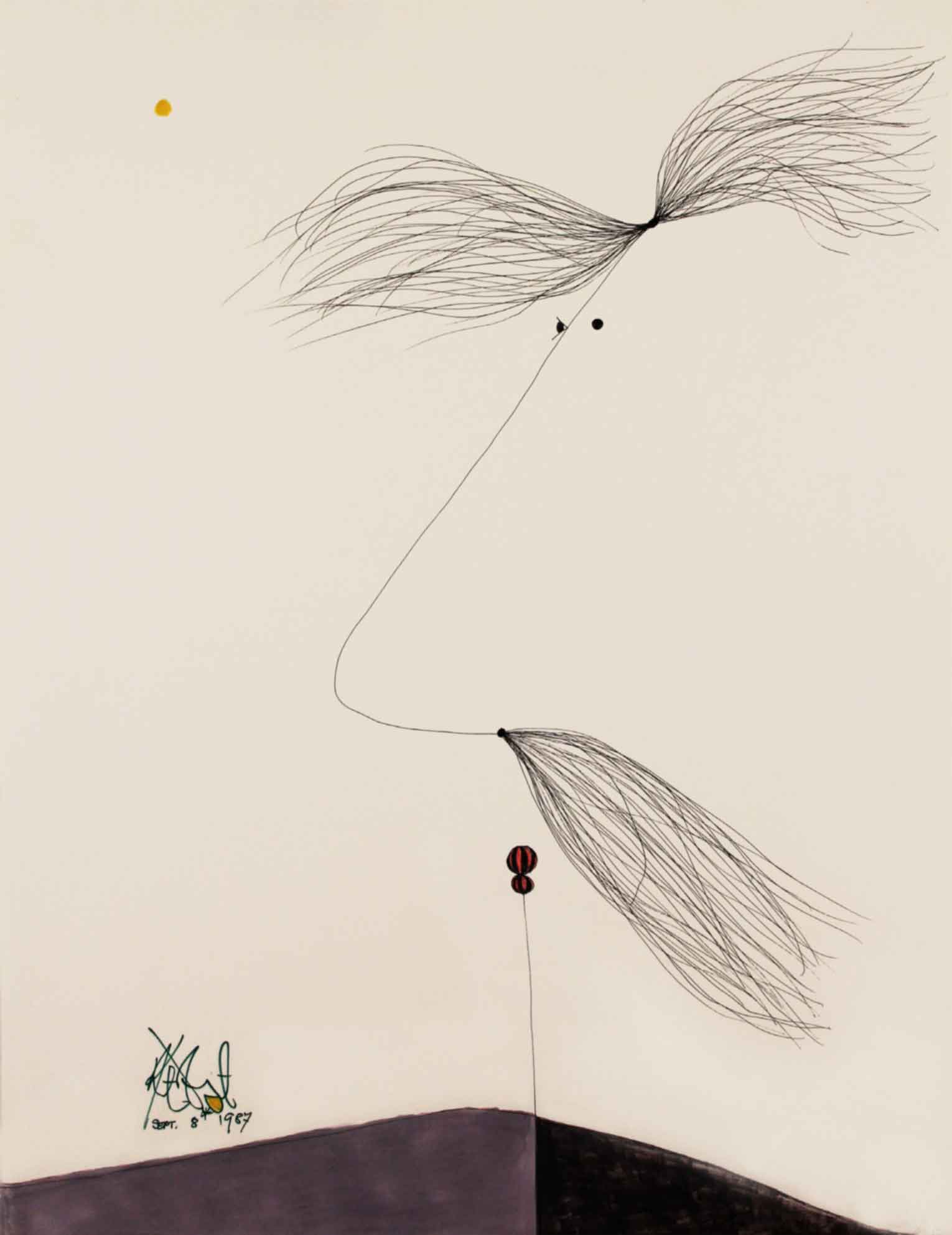

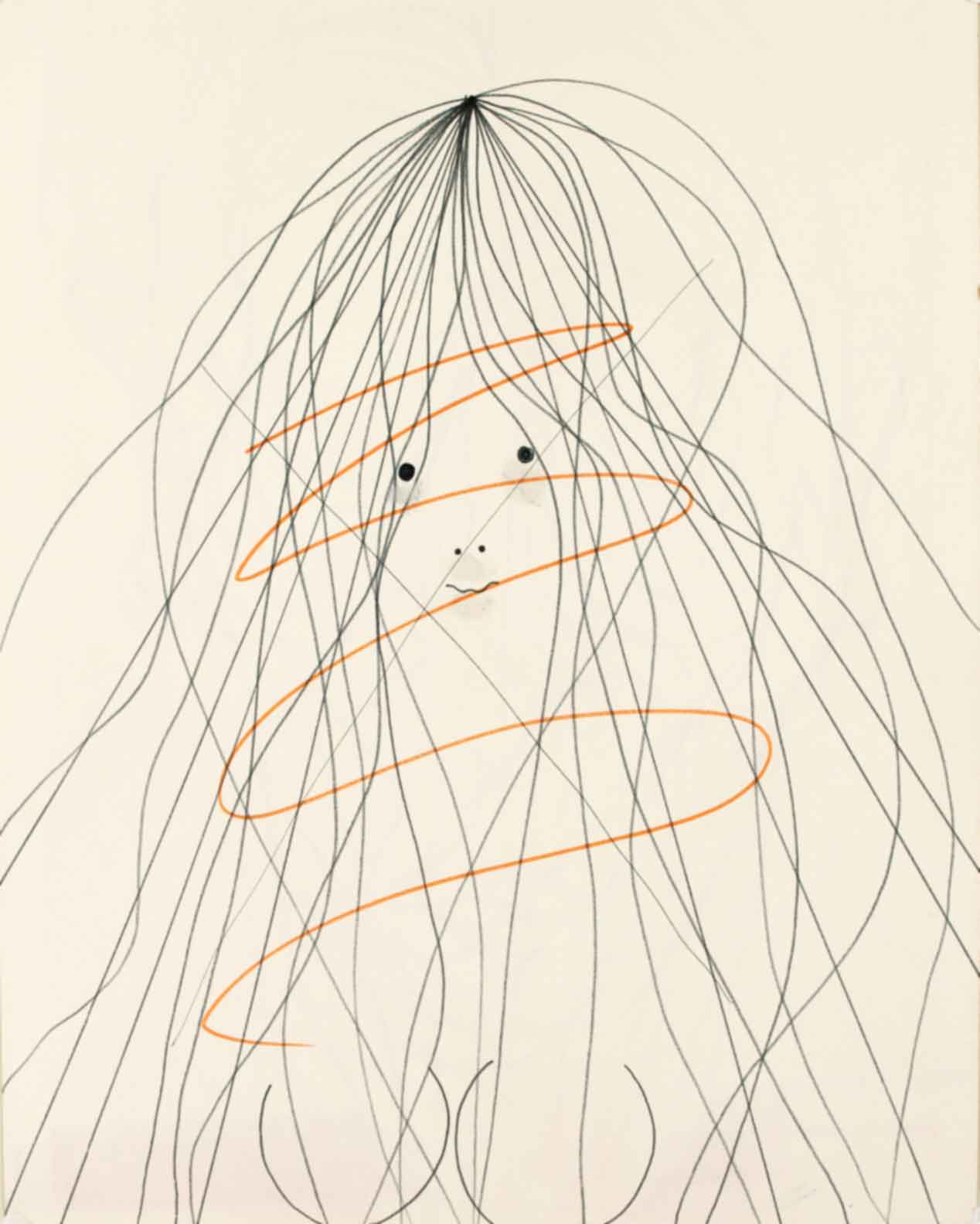

MY FATHER ,

THE DOODLER

NANETTE VONNEGUT

M y father once suggested that I make a piece of artwork and then burn it, as a spiritual exercise. I wanted to say, but didnt, Go burn all that writing you did this morning!

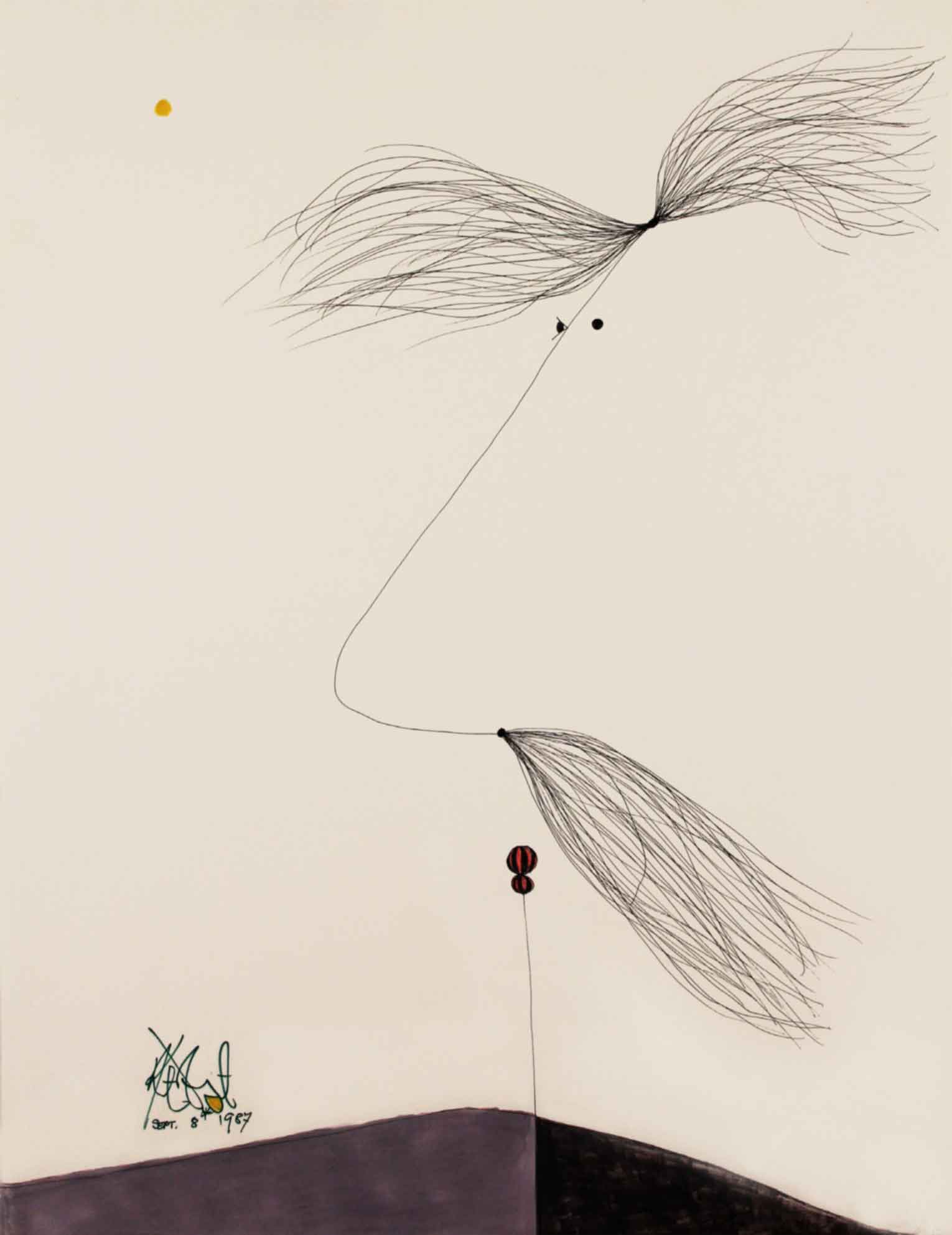

During one visit with me in New York City, my father sat down to finish a drawing he was working on. It was spread out on a coffee table and sprinkled with cigarette ashes. Without looking up, he said, This isnt very good, is it? I answered without hesitation, Burn it, dad, its no good! Beaming in appreciation, he quietly said, Yeah, youre right. He wadded up the drawing and dropped it on the floor, next to the trash can.

We were talking shop, and he was listening. He said he was tired of having to hit home runs all the time as a writer. A few days later he sent me a postcard: Darling DaughterI have always believed you to be a poet, so Please start writing poems, but rhyme them. No fair tennis without a net. LoveDad

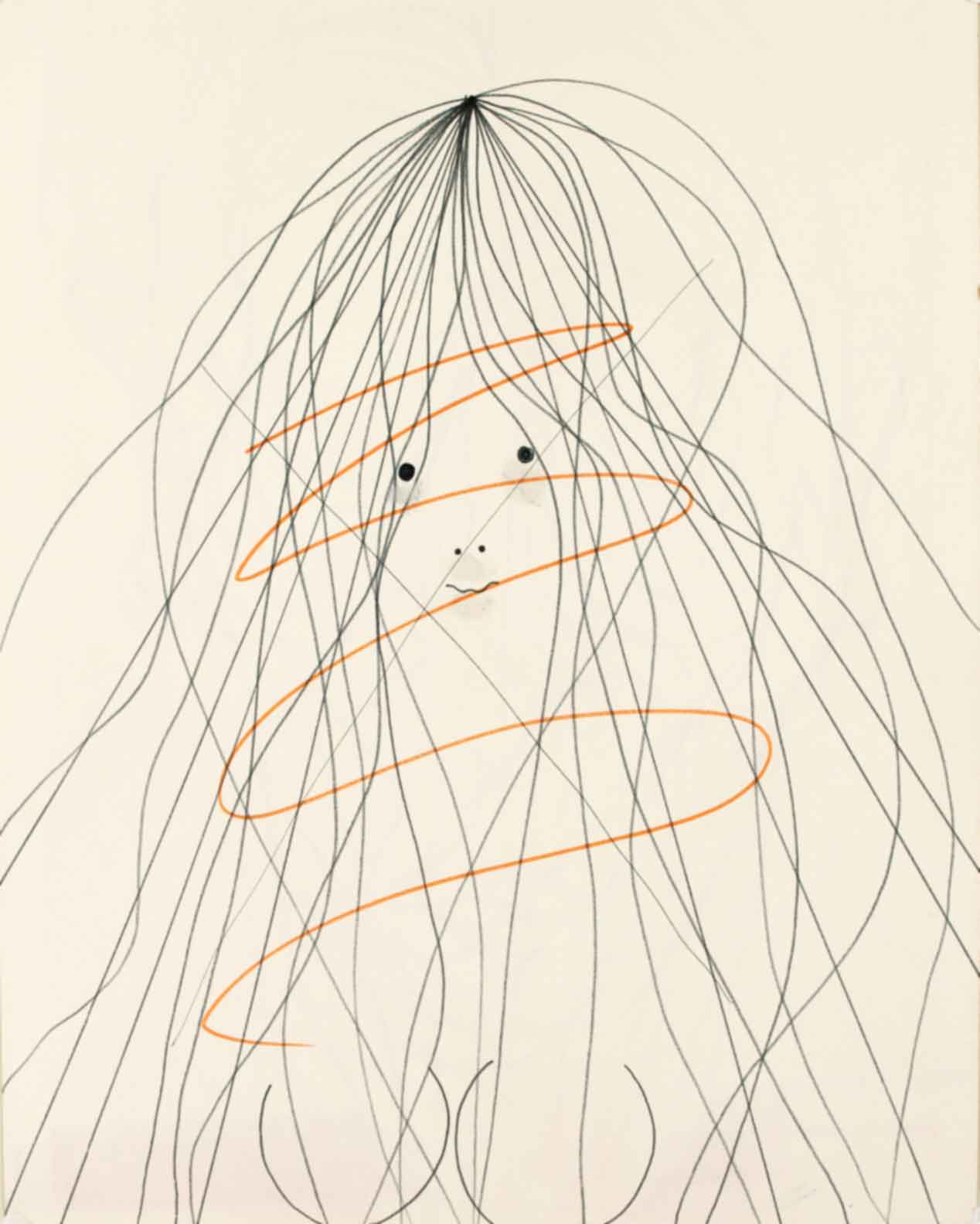

About these drawings: I received them in two unwieldy shipments sometime in the mid-1990s, not long after I had ordered dad to burn his drawing. He called to make sure they had arrived safely; otherwise he had no advice as to what I might do with them. In the throes of child-rearing, I stored them in flat files in my studio and spent little time with them. Honestly, at the time, I thought myself a bona fide artist because I went to Art School. I thought dad should stay in his writing corner, where he belonged, and I would stay in mine.

Remembering my father and the house on Cape Cod where I grew up conjures up a cartoon tornado, a spinning funnel with dozens of floating Siamese cats, two dogs, a piano, a bucket of baby-blue paint, a grandfather clock, a garden hose, my mother wearing an apron, and my father holding a cigarette and a lit match.

My father was more than a writer: he was the guy who never wore socks with his off-white, banged-up sneakers, who rarely left the house and was very regular about disappearing into a forbidden part of the house called the study. There were two doors you had to go through to get there. No one tried to pass through the second one. If you did, youd turn to ash because the room was booby-trapped with something having to do with creation. My father had proven himself worthy to be in that room, although I always worried about what was happening to him in there. I could hear the rapid-fire rat-a-tat-tat-tat of his typewriter and knew he was trying to wrestle big thoughts onto small pieces of paper, rat-a-tat-tat-tat tat tat-tat-tat At days end, he emerged from his study and charged headlong toward the sound of my mother frantically cracking ice for his predinner cocktail.

The days my father got his hands dirty were happier days. With vigor and rhythm, hed stomp a shovel into dirt with one flimsy, sneaker-shod foot to make way for bricks, shrubbery, and trees. Over a period of days, he built a large patio and turned our yard into a little Eden. To finish it off, he installed an old, eroded cement fountain he found at the dump and rigged it with a garden hose so water came burbling out of the lions mouth. Whatever work he was doing, he kept the white noise of Muzak playing in the background.

When my father did leave the house, it was usually a trip to the dump, where he salvaged beautiful old planks of wood and slabs of marble. Into one plank he carved these words: Beware Of All Enterprises That Require New Clothes, Thoreau, and turned it into a six-foot-long coffee table. He chiseled into marble the last words of Molly Blooms soliloquy in James Joyces Ulysses, and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes. In the heat of carving, he often nicked himself. Amused by his own scabbed-up hands, he explained, Jesus, that stuff was slippery and that blade was sharp!

Ye Shall Love One Another was painted on the mantel of our dining room fireplace one day. The next day, Go Love Without The Help of Anything On Earth and God Damn It, Youve Got To Be Kind showed up on other walls. The script was bold and elegant, lined in black and gold. My fathers creativity inspired my older sister to follow suit. In the large, curving stairwell she painted an epic scene of Satan wrestling an angel down to the pits of hell. Simultaneously I wrote, Shit, Fuckitty Shit in black magic marker on my bedroom wall, copying my fathers distinctive script.

Not long after my father died in 2007, I visited his childhood home, in Indianapolis. His father, Kurt Vonnegut Sr., otherwise known as Doc, designed and helped build the large, brick Craftsman/Art Decostyle house in 1923. As I walked through it, I noted my grandfathers artistry everywhere. I was struck by the beauty of a leaded-glass panel, set into the heavy, wooden front door, with their monogram, K & E (Kurt & Edith), cradled by a much larger, gently curved V. There was something very familiar in Docs letteringit was the same lettering I was copying when I wrote Shit, Fuckitty Shit on my bedroom wall.

There were more similarly designed leaded-glass panels inside the house. The designs were elegant yet simple and complemented the Craftsman-style tile and woodwork throughout the house. I felt my grandfathers spirit in every nook and cranny. A tremendous wave of affection for my grandfather, for his style, washed over me. I had never known him until then. At the rear entryway, I found the concrete slab Doc had poured that displays five Vonnegut handprints, arranged vertically according to age. My fathers baby handprint, at the bottom, includes the knitted cuff edge of his tiny sweater. Like the monogram on the front door, the handprints are dated 1923. The small wishing pond Doc created, which once held frogs and water lilies, and the remnants of an old garden in the big backyard were still there. I was electrified by the recognition that I had discovered my fathers origins.

My father once said, Where is home? Ive wondered where home is, and realized, its not Mars or someplace like that, its Indianapolis when I was nine years old. I had a brother and a sister, a cat and a dog, and a mother and a father and uncles and aunts. And theres no way I can get there again.

According to my father, his big brother Bernard, the science prodigy, designed weather systems in the basement of their home and sometimes sent rockets ripping through the dining room floor. I examined the dining room floor for telltale traces of mayhem, and was satisfied by a slight discoloration in one spot. I know little about my grandmother Edith, beyond the fact of her unhappiness, the legendary bathtub that she special-ordered to accommodate her extraordinary height, and her serious attempt at writing short stories for ladies magazines to bring in much-needed money.

Doc taught his daughter, Alice, how to throw a pot and glaze it and the art of lettering, and he instilled in her a love of craft and design. There is a surviving piece of work they made together, displaying my grandfathers skill and Alices budding promise as an artist. Oscar Bug, painted on an old piece of battered wood, is a terrifically silly cross between a mouse, a June bug, and a lobster, wearing giant boots, striped underpants, and a big bow tie. I imagine my father as a young boy, standing at Alices side, watching her create worlds out of mud and thin air and never wanting it to end.