For my grandsons, Louis and Elliot

First published in 2016

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

All rights reserved

Robin Quinn, 2016

The right of Robin Quinn to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 6926 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

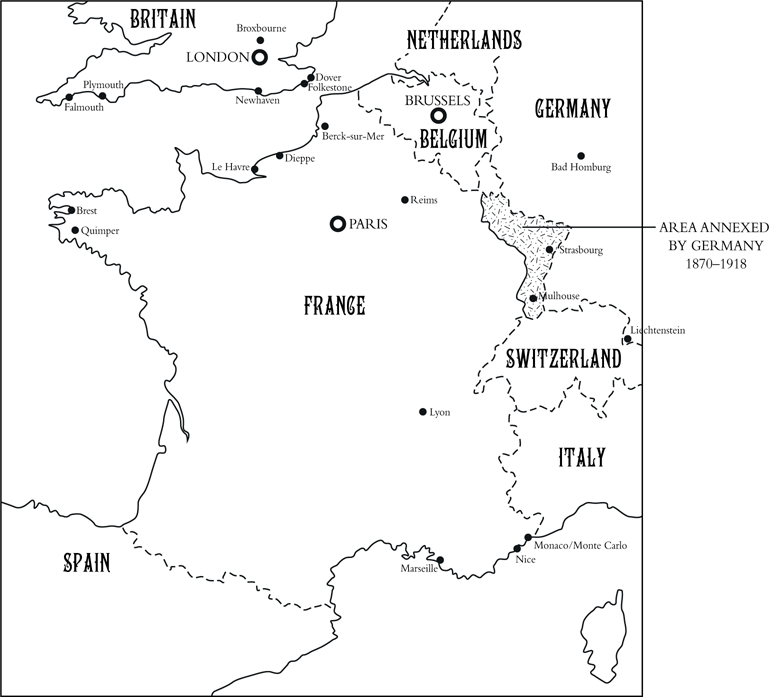

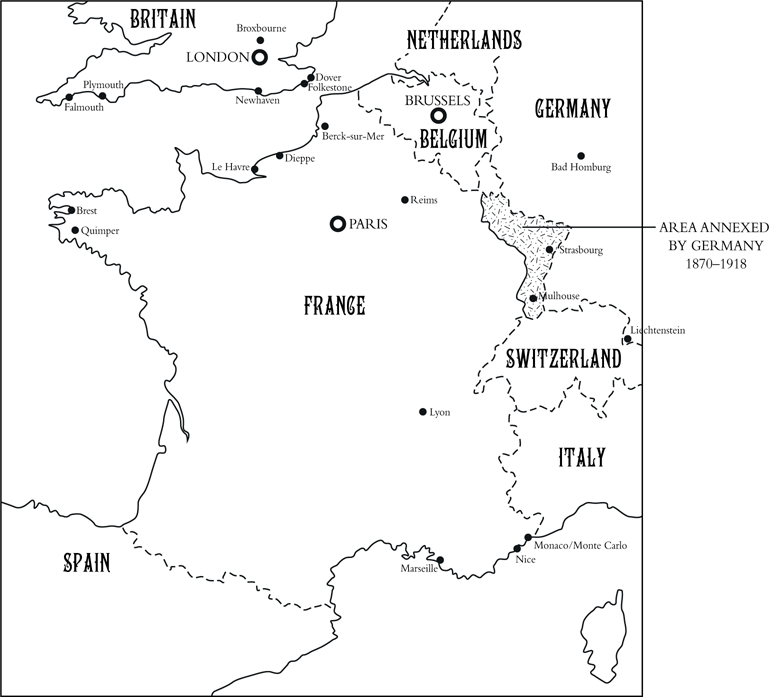

France and surrounding territories, showing places mentioned in the text.

INTRODUCTION

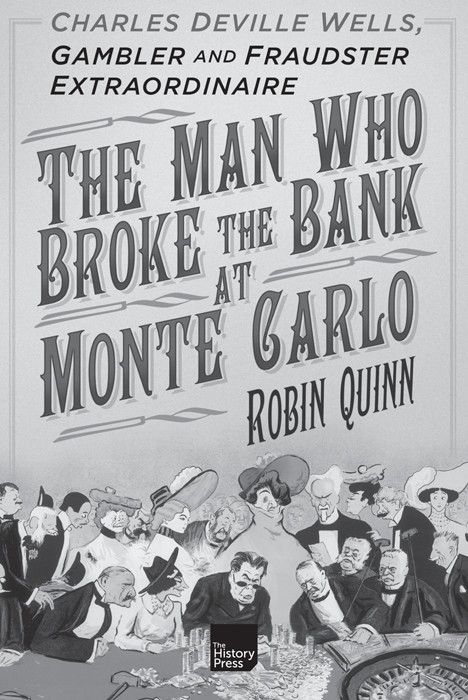

I had never realised that there really was a man who broke the bank not until a few years ago, when I was researching a completely unrelated topic. I knew, of course, that there was a song called The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo. My grandfather, who was born towards the end of Queen Victorias reign, used to sing it to me when I was a child. It had been one of his favourites.

A paragraph in a very old newspaper caught my eye: it was headed Man who broke bank at Monte Carlo dies in poverty or something similar. I was surprised to learn that he was a real person. And then I wondered what could have happened between breaking the bank and dying a pauper. I jotted something down on a corner of my notepad and carried on with more immediate concerns. But I never quite forgot that short article.

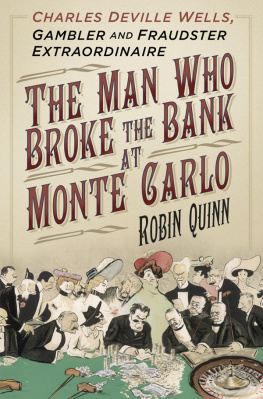

In the spring of 2014, I had just completed my first book Hitlers Last Army and casually mentioned to my editor at The History Press, Mark Beynon, that I had another vague idea in mind: a biography of the bank-breaker, Charles Deville Wells. Mark replied so quickly, he caught me unawares, Yes please, The History Press would love to publish the book, and the contract is in the post.

I hesitated for a moment. No book about Wells had ever been written before, but a great deal had appeared about him in the press over the years. The only trouble was that the reports seemed to contradict one another, making it hard to separate fact from fiction. Even a picture, which supposedly portrays him as a young man and appears on many websites, turned out to be of a completely different Charles Wells a serious-looking fellow who became mayor of Massachusetts, USA, in 1832.

No one seemed quite sure who Charles Deville Wells was, or where he came from, and the fact that he had used numerous false identities simply muddied the waters still further. He evidently spent many years in both France and Britain, and it was not at all clear how much of his life would have been documented.

But I decided to take a chance, and signed on the dotted line.

Researching a man who spent most of his life keeping one jump ahead of the authorities wasnt the easiest of tasks. But tracking down his activities and sifting through the many sources of information on both sides of the Channel has provided me with one of the most absorbing and satisfying challenges in my life. I have been helped in my search by many generous contributors, listed in the Acknowledgements. My thanks to them, and sincere apologies to anyone I may have inadvertently omitted from the list.

This is not a book which will tell you how to win money in a casino though there are plenty of others that claim to do so. Even so, there has to be some discussion here of casino games and of money. Im not a mathematician, a statistician, or an accountant, so Ive kept it simple, if only for my own sake. However, there are inevitably some occasions when the narrative turns to money matters. In these instances I have carefully avoided complex discussions of mathematics, probability theory and statistics, all of which have a marked tendency to make my head spin.

The only thing you really need to know is that one pound (1) in the late nineteenth century was worth about 100 today. By the 1920s, when this story ends, it was worth rather less about 80 in present-day money. In any case, such comparisons can never be more than a rough guide. Where it seems helpful to do so (which is quite often), I have placed the modern equivalent in brackets afterwards: for example, In one day he had transformed the 4,000 he had brought with him into 10,000 (1 million). Thankfully, the exchange rate between the pound and the French franc (fr.) remained rock steady at 25fr. to the pound for nearly all of the period of this book, relieving us of any unwelcome arithmetical complications from that quarter.

Although no previous book about Charles Deville Wells has been published, he is at least mentioned in a few works, and I have used these as source material where appropriate. But, for the most part, I have relied heavily on newspaper reports of the era. I consulted more than 100 separate titles, all listed at the back of this book. These do more than just tell the story as it unfolded day by day. The press also shaped public opinion, on the one hand, while reflecting the thoughts and viewpoints of their readers on the other. Sometimes we have to take what the papers said with a pinch of salt as we do today but on the whole they allow us to see events through the eyes of an earlier generation, while evoking the atmosphere of an era which is now long gone.

In quoting from these reports I have made minor changes to spelling, the use of capital letters, hyphens, and so on, for the sake of consistency. Where speech is reported, the actual words and expressions spoken over a century ago can sound surprisingly modern at times, but except for a few instances of slight paraphrasing for editorial reasons, the quotations are in fact unchanged from the original.

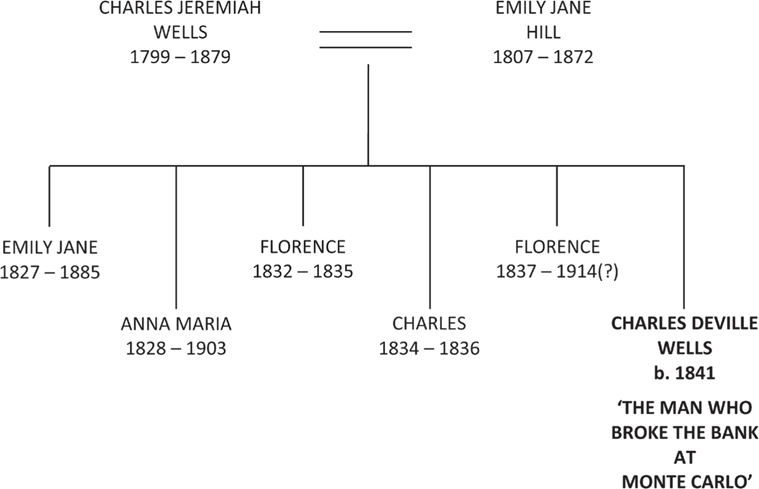

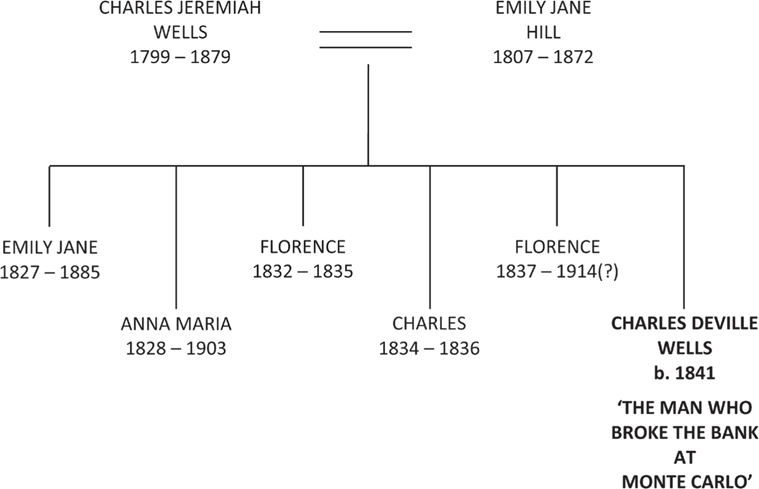

Wells family tree (simplified).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I could not have written this book without the help of the institutions and individuals listed here.

In Britain: British Library; Dr Francesca Denman; Guildhall Library; Jessica Handy (Unilever Archives); Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies; Intellectual Property Office; Alan Lawrie; Lloyds Register; London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Cemeteries; London Metropolitan Archives; National Archives; Royal Archives, Windsor; Ben Stables; Dr Isobel Thompson (Historic Environment Record, Hertfordshire County Council); Max Tyler (British Music Hall Society); City of Westminster Archives Centre; West Yorkshire Archive Service.

The extract from Queen Victorias journals (p. 70) was provided by the Royal Archives, Windsor, and is quoted with the permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Overseas: Bibliothque royale de Belgique; Brigitte Couplet; Bibliothque Nationale de France; Christian Labardens; Charlotte Lubert (Socit des Bains de Mer, Monte Carlo, Monaco); Martine and Jol Pairis; Nolle and Jean Pilon; Smithsonian Library (Washington DC, USA); Socit des Gens de Lettres (Paris); Michel Troubl; Philippe Valcq; and the local archives in Lyon, Marseille, Morlaix and Paris.

Next page