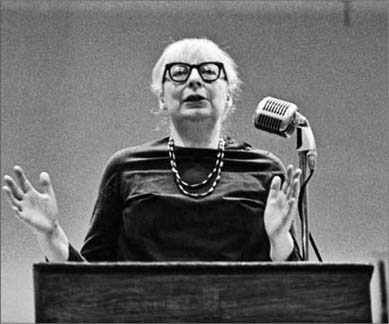

A master at the dais, Jane Jacobs famously turned her back on officials holding a hearing on the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Fred McDarrah/Getty Images

Anarchy and Order

The public hearing had already begun when she arrived. After stopping to add her name to the list of people requesting to speak, she headed toward the front of the auditorium, acknowledging the applause that rippled up from the crowd as she passed, a flash of white hair bobbing along the aisle, thick black glasses perched on an aquiline nose. She took a seat at the front of the hall.

The recipient of the applause was Jane Jacobs, a fifty-one-year-old author and activist, whose book The Death and Life of Great American Cities had made her synonymous with efforts to fight urban renewal projects that destroyed existing neighborhoods. On this pleasant spring evening, about two hundred residents of Manhattans Lower East Side, Little Italy, Greenwich Village, and what would later be known as SoHo had gathered in a high-school auditorium for a public discussion of the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway. They sat scattered in rows of fold-down seats, fanning themselves with pamphlets and craning to see the person who was speaking at a microphone in front of the stage.

The meeting had been called by officials from the New York State Transportation Department who believed the Lower Manhattan Expressway would alleviate street traffic on clogged Manhattan streets and increase efficiency for drivers looking to cross from New Jersey to Long Island. The superhighway was to be elevated, providing ten wide lanes that would soar above the crowded city streets. But its foundation would cut through dense city blocks that had existed almost since the Dutch had settled Manhattan nearly four centuries before. Even the city officials knew that the price of this monument to progress would be steep: the government would have to evict twenty-two hundred families, demolish over four hundred buildings, and relocate more than eight hundred businesses to clear the way.

Though the ostensible purpose of the meeting was to collect opinions about the project, it had been hurriedly scheduledto make sure testimony was gathered before legislation passed that required an even more extensive public approval process. For years, there had been clear opposition from the neighborhoods residents, who were now irritated that they had to state their case one more time. The manner in which the meeting was being conductedthe microphone faced toward the audience, not the officials the residents were nominally addressingsuggested that state officials were just going through the motions.

As a stenotypist moved her hands rhythmically over the key tabs of her machine off to the side, the officials frequently interrupted speakers to remind them of a time limit. When a man talking about the dangers of air pollution was told to speed it up, the audience began shouting questions to the officials: What changes had been made to the proposal? Was there anything better about the latest version of the roadway plan? The transportation men shrugged; they were only there to provide basic information and hear testimony, or rather bear witness to the fact that testimony was being given. The crowd began a chant: We want Jane. We want Jane.

From the seat shed taken near the front of the auditorium, Jane Jacobs made her way up the stairs and onto the stage. Its interesting, the way the mike is set up, she observed tartly as she reached the microphone. She was calm, and her expression was matter-of-fact. At a public hearing, you are supposed to address the officials, not the audience.

The chairman of the hearing, John Toth of the New York Department of Transportation, bounded down from the stage and turned the microphone around. But Jacobs turned it right back.

Thank you, sir, but Id rather speak to my friends, Jacobs said. Weve been talking to ourselves all evening as it is. The crowd roared with laughter.

After a pause, Jacobs continued. What kind of administration could even consider destroying the homes of two thousand families at a time like this? With the amount of unemployment in the city who would think of wiping out thousands of minority jobs? They must be insane. The expressway would destroy families and businesses, factories and historic buildingsin short, entire neighborhoods. Nobody wanted it, she said. But the government wasnt listening. It was as if the officials backing the project had parted from reality.

The city is like an insane asylum run by the most far-out inmates. If the expressway is put through, she warned, there will be anarchy. The officials in attendance were mere errand boys, and the residents had to make sure they would take a single message back to their bosses: that the people of lower Manhattan would not stand for this highway. But this message couldnt be mere words, she said; it had to be a physical demonstration, a defiant march. She called the crowd forward, and about fifty people, some carrying placards, moved up the stairs, with Jane leading the way.

Toth rose from his seat as the first of the protesters stepped onto the stage. You cant come up here. Get off the stage!

We are going to march right across this stage and down the other side, Jacobs responded calmly, as if to a petulant child.

Arrest this woman! Toth frantically called to the police officers assigned to the hearing.

As Jacobs led the crowd onto the stage, the stenotypist gathered up her machine and clutched it to her chest, proclaiming that she was not an employee of the state, had nothing to do with the expressway, and had just purchased the brand-new equipment herself. With her free hand, she lunged out at the marchers to keep them away, and struck Jacobs. It was more jostle than shove, but a patrolman intervened.

Why dont you just sit down here, Mrs. Jacobs, he said, gesturing to a folding chair at the rear of the stage. She went to the chair and stood behind it, resting her hands on its back.

As more and more marchers made their way to the stage and the stenotypist tried in vain to gather her handiwork, rolls of tape tumbled onto the floor. The defiant New Yorkers, seeing an opportunity, tramped on the unraveling streams and picked up clumps and tossed them in the air. Without the stenographic notes, the officials couldnt prove they had satisfied the requirement to gather public input. Jacobs had, in fact, discussed this with a few selected residents prior to the meeting: if the record was destroyed, it would be as though the hearing had never happened, delaying the project and buying more time. As Toth and the transportation men scurried to retrieve what they could, Jacobs climbed down from the stage and took to the microphone once again.