To my brave, talented, and patient coauthor, Natasha Stoynoff... thank you for tolerating my lunacy and years trapped in a New Jersey hotel room with me force-feeding you pasta at 4 AM .

Many thanks to my true friend and loyal supporter, Vincent Brana, who has been there for me from the beginning.

To my agent, Frank Weimann, at Folio Literary Management and to Glenn Yeffeth and the team at BenBella BooksIm grateful for your belief in us and your hard work on this project.

Thank you to all my crewspast, present, and future.

And finally, thank you to my daughter Lauren. You are my best girl and the reason I get out of bed every morning.

Structure, organization, discipline, and control: You must fight every day for success. This is how I live my life.

T HOMAS G IACOMARO

King of Con

January 30, 2018

THOMAS GIACOMARO was the owner and president of dozens of million-dollar companies and M&A consulting firms that acquired, consolidated, and sold privately held companies in the fuel, energy, trucking, transportation, commercial and residential, recycling, and waste industries. He graduated from William Paterson University with a degree in business administration.

NATASHA STOYNOFF is a two-time New York Times bestselling author with thirteen books to her credit. She graduated with a BA in English and psychology from York University in Toronto and studied journalism at Ryerson University. Natasha began her career as a news reporter/photographer for the Toronto Star and columnist/feature writer for the Toronto Sun. A two-time winner of the Henry R. Luce Award for excellence in journalism, she was a longtime staff writer in People magazines New York bureau and a news reporter for TIME. She currently writes an ongoing series about sexual harassment and assault in People called Women Speak Out. Natasha lives in Manhattan and is finishing her second screenplay.

Dad calmly walked back to the car and dropped the blood-streaked bat on the floor beside my feet.

A prison shrink once told me that by the time were seven years old, we are who we are for the rest of our lives, and theres usually shit-all we can do about it. Our brains are hardwired forever, and its too late to change anything.

Too late to go from bad guy to good, or from sinner to saintas Father Stanley might have said. Unlike the shrink, Father Stanley thought you could change your fate in the time span of one confession.

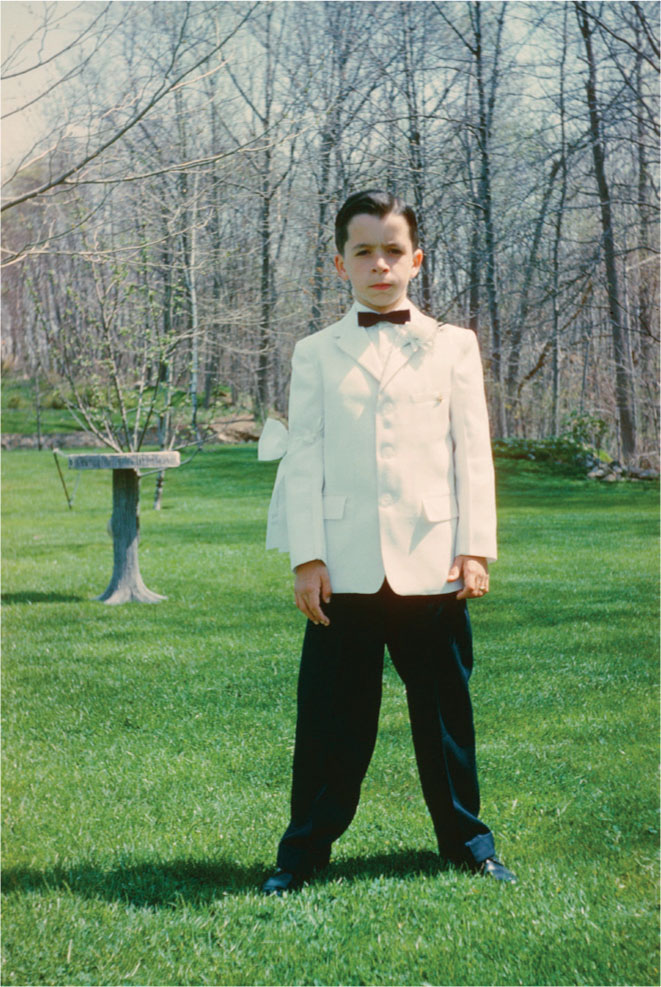

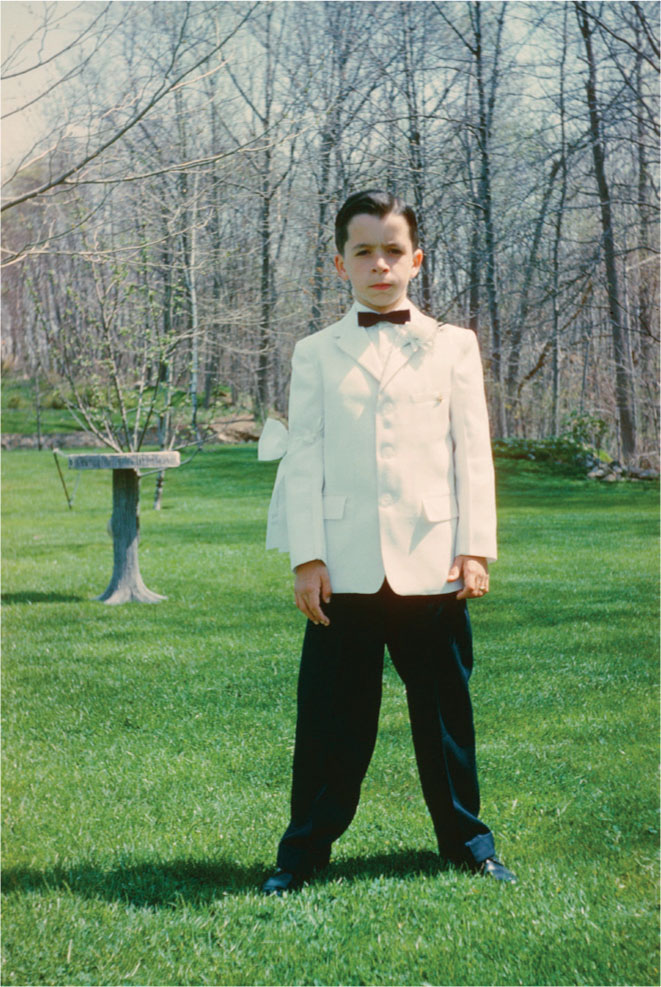

Youve reached the age of reason, Tommy, he pronounced, solemnly, as I knelt in the jail-cell confines of the dreary confessional to make my very first confession, soon after my seventh birthday.

From this day onward, you are morally responsible and accountable for all your actions. You have free will to choose your behavior.

Well, I gotta be candid with you. If Father Stanley was delivering a message from his god, my parents and I never got the memo.

Because by 1960, the year I reached this age of so-called reason, my father had been beating the crap outta me for years and I was already an accomplished thief. So apparently the Giacomaros of North Haledon, New Jersey, didnt do so good with this morally responsible accountability thing. Or ting. Thats how the guys I run with say it.

By my first communion I was already a crime boss.

My father, Joseph, went out bowling and card playing every Friday night. Hed return home stinking of booze and strange perfume, carrying a thick wad of bills hed won gambling. Dad was an accountant; he was smart with numbers and knew how to get money outta people from right under their noses.

And so did I.

Id be wide-awake when he staggered in at 4 AM even as a kid, I slept only three to four hours a night, a habit that wore down my mothers sanityand listened closely as his footsteps echoed down the hall, into the den, then downstairs to the basement where hed pass out asleep. He always slept in the basement on Friday nights so my mother wouldnt wake up and know what time he got home.

Id lie motionless under my blankets until I heard his floor-rumbling, boozy snoring through the floorboards directly below me.

And thats when Id rob the motherfucker.

Armed with a mini flashlight, Id slip out of bed, move silently down the hall, and tiptoe into the den. Id quietly slide a chair across the floor until it nudged against the bookcasethats where he stashed his wallet, on the top shelf. If I stood on the chair and stretched my arm as high as it could go and fished around, sooner or later my gloved fingers would bump into the thick leather lump. Yeah, I wore gloves when I sleptstill do, but Ill get to that later.

Hitting up dads wallet was like winning a lottery. Its what we in the money-stealing business called easy moneythe sweetest kind. It was always a sure bet. Id peel four or five twenties from the bulging billfold and return it to the shelf. Back in my room, Id hide the money in a hole I cut in my mattress.

Early Saturday morning Id knock on Eddy LaSalles door to come out and spend the ill-gotten loot with me. Eddys dad had some important job as a business executive in Hoboken. In looks and personality, Eddy and I were exact opposites. I was dark, wiry, frenetic, and never shut up; Eddy was tall, shy, blond, and stocky. But we understood each other, Eddy and me. We both had trouble at home and there was shit-all either one of us could do about it.

But on Saturday mornings with my dads twenties burning a hole in my pocket, we hadnt a care in the world. Back then Bazooka chewing gum cost a penny a piece, and I was a kid with a hundred bucks to blow. I was a fucking millionaire.

First wed go to the Rendezvous, a nearby shopping emporium that sold girlie magazines and comic books, and stock up on Superman. Two doors down was Jays Luncheonette, where wed hoist ourselves onto the counter stools and order deluxe cheeseburgers, French fries, and all the Coke we could stomach.

I loved the feeling of importance and power that the money gave me. Contrary to Father Stanleys little morality lesson, I had no remorse about stealing from my fathers wallet. In fact, I was pretty confident that it was my moral responsibility to do so.

I ate fast, wolfing down the food like I was starving, and I was. But it wasnt a physical hunger. I was feeding emptiness, stoking a burning anger, and numbing a pain inside of me with the stolen money and fast food. Every bite I took was a conscious fuck you to my father.

Thisll show him, Id say, as we sat stuffing our faces. Eddy would shove ketchup-drenched fries in his mouth and nod. He knew exactly what I meant.

I was five years old when I first saw my fathers fierce Sicilian temper. We were driving home from a relatives house on a beautiful spring afternoon. My mother, Yolanda (Lonnie), was in the passenger seat and I was sitting in back reading a comic book. Even my father seemed in a rare good moodthat is, until the driver next to us swerved in front and cut him off. That driver obviously didnt know my father was the last person in the world you want to fuck with, and until that day, neither did I.

Joseph Thomas Giacomaro had been a technical sergeant in the US Marine Corps and had seen combat in both World War II and Korea. At a lean 58, he was neither tall nor beefy, but that didnt matter when you were a trained expert in hand-to-hand combat.

He returned from Korea after being discharged in 1954 with a trunk load of combat memorabilia: his banged-up canteen; a utility belt with a leather holster for a sidearm; two standard-issue field blankets; his camo-green Marine Corps jacket (which he wore once a week when he mowed the lawn); and his prize possession, a menacing, black-handle bayonet with a ten-inch blade. He kept the bayonet locked up in a closet and once, just once, he demonstrated how it was used.

Next page