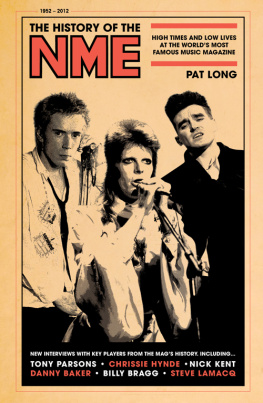

First published in the United Kingdom in 2012 by

Portico Books 10 Southcombe Street London W14 0RA

An imprint of Anova Books Company Ltd

www.anovabooks.com

Text Pat Long, 2012

Volume Anova Books Company Ltd, 2012

First ebook publication 2012

Ebook isbn 978-1-907554-77-3

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

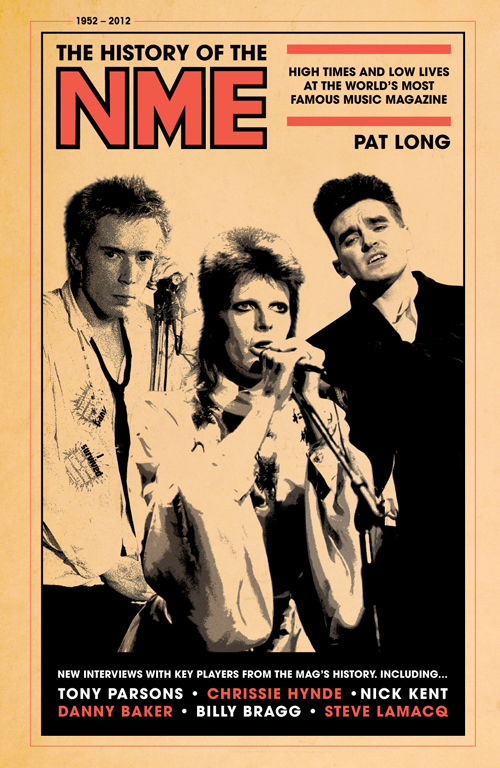

Introduction

Friday afternoons at NME were always the best. Most of the copy would have been dispatched to the printers by lunchtime and, barring any cataclysmic news event, the following weeks newspaper would be complete. In the 1970s the staff of the paper wouldve celebrated with a bottle of chilled champagne and a joint the size of a small canoe. During my time working there in the noughties we made do with the ritual weekly plate of fish and chips in the work canteen and a couple of cans of whatever warm lager had been sent to the office by one of the magazines commercial sponsors. The volume of the conversation and the music on the stereo would grow. A few members of staff would start listlessly kicking a football around. Others would be ringing press officers and record companies to get themselves on the guestlist for the weekends gigs. Expenses claims would be constructed, often applying greater levels of attention to detail and imagination than had previously been spent writing the three-page cover interview with The Libertines or Kasabian. Freelance photographers would float in to huddle around the lightbox, proudly displaying the contact sheets of their latest shoot with Black Rebel Motorcycle Club or The Coral. While my colleagues were busy, I would sneak off downstairs to the windowless basement room where the huge bound volumes of NME back issues were kept. Just accessing the IPC archive felt like being in a Bond film. The basement could only be accessed by a special lift; once inside you moved a set of towering mobile bookcases by rotating a huge metal wheel like that of a Swiss banks bullion safe. But once inside, what riches there were within those yellowing pages. Id marvel at ancient live ads featuring the strange and exotic names of moderately successful but now forgotten bands Hatfield and the North! The Close Lobsters! Atomic Rooster! or features that went on for thousands of words before the band was even mentioned. But mostly Id just feel jealous.

In my time at the NME wed got jaded and cynical. Hardened music fans, we were disillusioned at how rock music had become just another cog in an industrial entertainment process, a leisure option like going to Center Parcs or buying a Chelsea season ticket. Our forebears wouldnt even countenance such thoughts. For them rock music was an elemental life force that had to be nurtured and protected with well-spun words and the occasional snarky, punning headline. For NME journalists, writing passionately about rock music was a way of making sure that it was always more than just a commodity: sacrifices of health, sanity and very occasionally even life were made in the NME journalists noble yet quixotic pursuit of rock myth. There they were in the IPC archive, like the Dallas bystanders captured in Abraham Zapruders 18-second Super 8 footage of the Kennedy assassination: watching, slack-jawed and occasionally aghast as pop-cult history was made. Kurt Cobain ODing. Richey Manic disappearing. The first-ever Led Zeppelin gig. Hendrix setting fire to his guitar onstage at the Finsbury Park Astoria. Excitable early interviews with The Rolling Stones or Blur. The Smiths splitting. Bowie making a fascist salute at Victoria station. Smoking dope with the Happy Mondays or Bob Marley. Reviews of forgotten groups at extinct pub venues. A treasure trove of myth and memory.

No other country in the world has anything like the weekly music press, but then no other country in the world takes music as seriously as we do. Every morning at NME youd open your post with a mixture of glee (free CDs!) and trepidation (abusive letters written in green biro!). In 2003 I had threatening voicemails from a man with a West Country accent left on my office ansaphone every day for a month. My crime? Writing a small but dismissive review of a new single by the Stereophonics. I didnt mind, really: for four generations the weekly NME has provided a crucial cultural lifeline to the bored and disaffected around the world. If one man was driven to a sexual-sounding Cornish rage by my casual cruelty towards Kelly Jones then that was clearly a price worth paying.

There arent many people who read the New Musical Express regularly for any length of time that have ever truly shaken off its grip. Once, on the way back from reviewing a late-night gig, a Clash-loving London taxi driver asked me what I did for a living. When I told him, he almost crashed the cab with envy and amazement, before telling me a story about losing his money and shoes at a Sham 69 gig in 1980 and having to walk home eight miles, barefoot but content.

Music is such an inescapable part of the British cultural landscape that its strange to think of a time when it wasnt ghettoised in a weekly newspaper, when families didnt spend their summer attending well-provisioned inter-generational rock festivals, when parents didnt swap music with their teenage children. Once the pages of NME were literally the only place in the world where you could find out where Red Lorry Yellow Lorry or Kingmaker or the Groundhogs were next playing in your town. Now, of course, we all know everything instantly. Its a fact that, thanks to digital technology, the soundtrack to our lives is richer and more varied than at any point previously, but its also meant that NME has suffered the same loss of readership, advertising revenue and influence as all print media. You dont need to be a romantic to think that, somehow, thats a shame.

The history covered in this book ends roughly about the year 2000, two years before I started working at the NME. This is partly because the digital media revolution that has occurred since the start of the 21st century would merit a whole book in itself, and partly because I wanted to avoid having to make predictions about the future of the paper. The NME of today is never as good as the one we grew up reading, of course, but despite the naysayers, its proved resilient enough to be the last of what was once a handful of weekly music papers still appearing on newsstands.

But thats today. Thats now. This book is about then. Its about how a Tin Pan Alley trade rag became one of the most important and influential magazines on the planet, despite being staffed by people who could often barely function in the real world. Its about how the weekly music press developed an influence on British culture out of all proportion with the size of its readership, about how the values and ideals of the underground were sneaked into the mainstream via a weekly music paper published by a vast multinational publishing company. Its about the British love affair with rocknroll music and the strange, talented, obsessive, wonderful characters that chronicled a whole culture. Inside are brand new interviews with all of these people. But mainly its about fights and drugs and breakdowns and strikes and rock and reggae and punk and ska and acid house and Britpop, about the Sex Pistols and David Bowie and Public Enemy and Oasis and The Smiths. Its about the