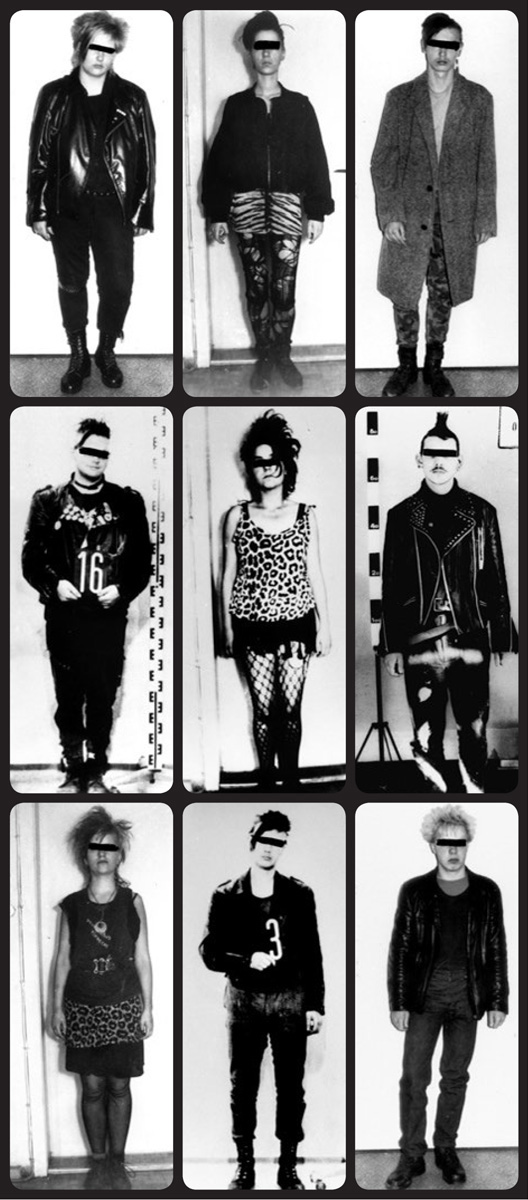

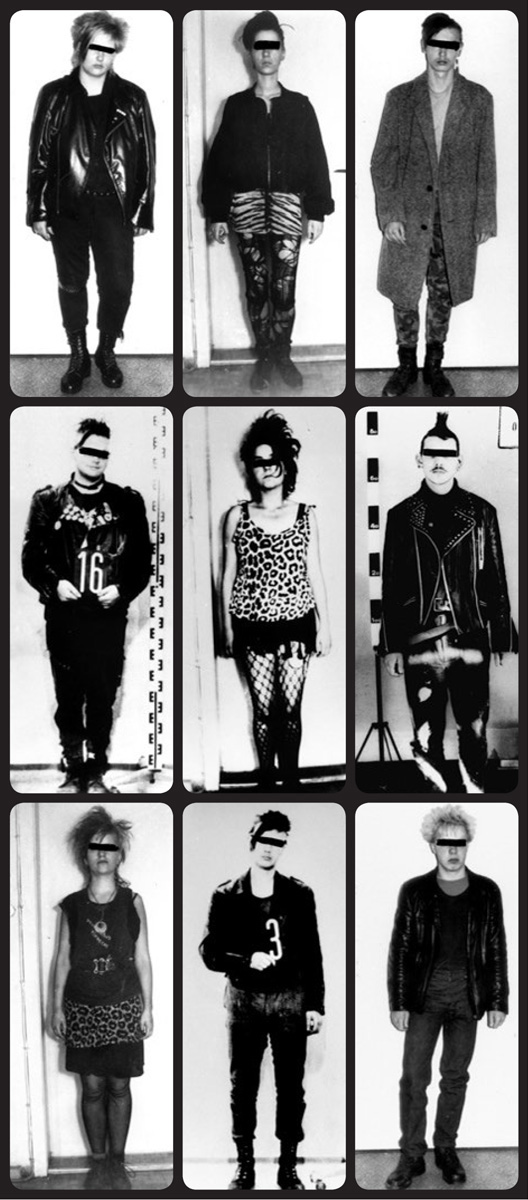

Police mugshots of East German punks

Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the Former German Democratic Republic (BStU)

Burning

Down The

Haus

Punk Rock, Revolution,

and the Fall of the Berlin Wall

By Tim Mohr

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2018

Contents

Preface

When I arrived in the eastern section of Berlin in 1992, Id never seen any place like it. Id never been to Germany or Eastern Europe before, and here I was in a high-rise student housing complex out near East Berlins zoo, Tierpark. At first the city seemed to fit the East Bloc stereotypes Id grown up with in suburban America: it was the grayest place Id ever seen, cloudy and cold, shrouded in coal smoke. Add to that the eerie sound of zoo animals howling in the distance and the constant fear sown by rumors of roving gangs of skinheads, and my initial impression of East Berlin was grim.

But I quickly discovered a scene exploding with color and creativity behind the dilapidated, shrapnel-pocked faades of the central East Berlin boroughs of Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg, and Friedrichshain. Hidden behind unmarked doors, down ladders in empty lots, nestled among the crumbling bricks of a candlelit basement or a disused cistern, in the attics of half-destroyed buildings, even in abandoned bunkers and bank vaults, a kaleidoscopic new city was taking shape. The bars and clubs that made up this netherworld were dark and dirty, with extension cords meandering down from some distant outlet to power their sound system and a couple of buckets of water behind the bar providing the only means to wash glasses. They were radically egalitarian. They were open and welcoming to an outsider like me. And they were so much fun I sometimes awoke the next day wondering if it had all been a dream. Once in a while Id wake up and find I was still in a club, only on a different day. Some nights the bar staff would leave and tell us stragglers just to lock the door when we left. In warm months, sometimes weit quickly became we in Berlin in those dayswe, the people, together, the DJs and dancers and partyers, we would leave the club and go scale the wall of a municipal pool complex and swim naked together as the sun came up. Some of the venues existed for only a night or a few weeks. Others lurked around for decades. The people who congregated in them refused to sit passively aside while the city tried to find an identity and slowly determine where it was going. These people set their own agenda, created their own style, controlled their own environment. They came up with the blueprint not just for a new Berlin, but for a new way of lifea Berlin way of life.

I soon started DJing in some of those clubs and bars, and continued to spend long nights in many more. I moved away from the zoo, first to Friedrichshain, then to Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg, and a stay that was supposed to last six months stretched out for a year and then another and another and another. That Berlinthe shadow city being built largely out of sight and with utter disregard for the other one being thrown up in places like Potsdamer Platz and, later, along the banks of the river Spreefundamentally changed my life and the way I think.

And it was in those clubs, during those years, that I first met East German punks and learned about the secret history of punk rock under the dictatorship. Ostpunks, or Eastern punks, ran or worked at most of the places I hung out; they had set up nearly all the first bars and clubs in the East and established in the process the ethos of the fledgling new society being built almost from scratch after the fall of the Berlin Wall. This kaleidoscopic world I had fallen in love with was their world, their creation.

At the time I had no idea I would eventually become a writer. But to an American reflexively skeptical toward the Reagan mythology surrounding the end of the Cold War, the story of East German punk seemed unbelievably importantperhaps more important than even the participants themselves realized. Here were the people who had actually fought and sacrificed to bring down the Berlin Wall.

My initial belief in the importance of this story was reinforced after I returned to the U.S. and recognized an ominous echo in developments in my own country: mass surveillance on a scale the Stasi could only have dreamed about, the widespread use of insidiously pliable charges like failure to comply with a lawful order to make arbitrary arrests, the struggle of protest movements such as Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and #NoDAPL in the face of a complacent or even hostile society.

In the West, we tend to harbor smug, simplistic views of the old Soviet Bloc and to dismiss out of hand comparisons of our system to authoritarian regimes like the one in East Germany. Its worth noting, however, that East German policeunlike our owncould not murder people in the street with impunity. Even today, we trot out images of foreign police brutalizing protesters in other countries to intimate the illegitimacy of governments in places like Egypt, Turkey, or Ukraine. But we rarely look in the mirror.

Our current inability to control state-sanctioned violence could not be more cleareven if white America goes to great pains not to acknowledge it. But perhaps even in an era when local American police departments deploy military equipment against protesters, use surveillance aircraft and lethal drones, and maintain CIA-style black sites, there is still hope. Perhaps this storyabout a bunch of unarmed, unruly teens and the cracks they managed to kick in the seemingly unbreakable system of repression in East Germanyis even more important now than when it first captured my attention. Back then I was fascinated to get to know people who had helped resist and eventually cast off the dictatorship. But I never imagined their stories might be of personal use to me and my fellow citizens in the Land of the Free.

East German punks used to spray-paint the phrase Stirb nicht im Warteraum der ZukunftDont die in the waiting room of the futureon walls in Berlin. It wasnt about self-preservation. It was an indictment of complacency.

It was a battle cry: Create your own world, your own reality.

DIY.

Revolution.

Burning

Down

The Haus

Official youth culture in East Germany: a Free German Youth rally

Harald Hauswald / Ostkreuz Agency

Introduction

By the late 1970s the Berlin Wallactually two walls with a notorious death strip between themhad been up for little more than fifteen years, but it had already become a fact of life. A generation had grown up with it; its history and the details of its construction barely mattered anymoreit was a booby-trapped concrete reality, the physical embodiment of a division of the world that felt as if it could go on forever. The young on either side accepted the Berlin Wall as permanentit had always been there and probably always would be.

Every aspect of life on the east side of the Wall was hyper-politicized, and nothing more so than popular culture. Already in 1945, several years before the official founding of East and West Germany as countries, American military observers were struck by the speed with which the Soviet Union fostered a renewed cultural life in the East after World War II. The Soviets did this not only because of its potential pacifying effects on the populace but, as American officials remarked, because they seemed to believe in the inherently edifying qualities of cultural institutions. A dozen theaters, two opera companies, five major orchestras, and countless cabarets and smaller music ensembles were established in the Soviet zone within two months of wars end. Of course, at the same time, Soviet secret police jailed 150,000 political enemies, a third of whom died from the harsh conditions in the prison camps. Between 1945 and 1947 the Soviets helped the German communist party found national organizationslike the Free German Youth,

Next page

![Marco Thiede - Human Punk For Real: An Autobiography [English Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/391913/thumbs/marco-thiede-human-punk-for-real-an.jpg)