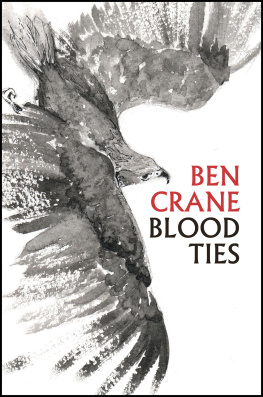

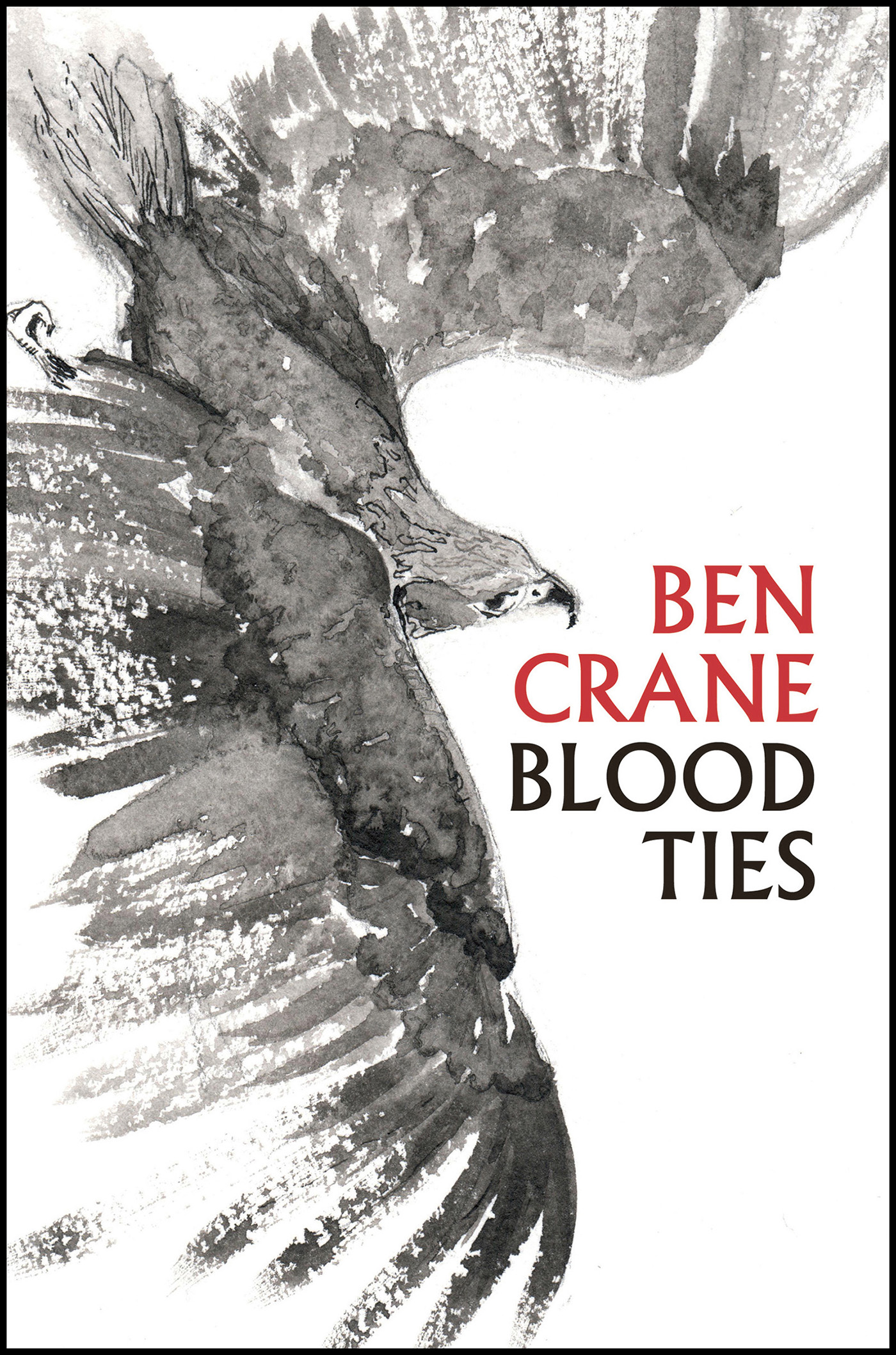

Ben Crane - Blood Ties

Here you can read online Ben Crane - Blood Ties full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Head of Zeus, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Blood Ties

- Author:

- Publisher:Head of Zeus

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blood Ties: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Blood Ties" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Blood Ties — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Blood Ties" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

|

An uncannily brilliant evocation of the falconers art and a moving story of a mans discovery of how to be a father.

This is a book about a mans relationship with hawks, and his self-education as a falconer, and about his discovery that despite his Aspergers Syndrome, which hampers his normal social interactions, he can forge a loving bond with the young son he thought he had lost. He rediscovers his full humanity through his commitment to the training of falcons and his love of the natural world.

Ben Crane writes with uncanny accuracy and lyrical precision about the intricacies of birds behaviour and their instincts. He has a ruthless eye for the minute details of natural processes of plumage, the patterns of flight, of killing, death and decay. Hes as clear-eyed about himself and his detachment from ordinary human society as he is about the flight of peregrines and goshawks.

Here is nature writing at its very best, interwoven with an affecting human story and an account of how a man mastered the ancient craft of falconry.

To Pete for the space,

to Steve and Hollie for the tools,

and E and J for the pant-stretching mirth

In the warm, womb-like space of the cottage, the light from the open fire flickers and casts dull shadows of birds across the wall. On my gloved hand is a slender, lightweight and beautifully patterned female sparrowhawk; to my left, a smaller but no less impressive male. Both hawks emanate a quiet, self-contained calm. A fine balance of delicate precision, coiled, unsparing instinct, contained within a gossamer skein of feather, skin, muscle and bone. They remind me of that thin slither moment just before a jack-in-the-box pops. Both hawks arrived from the wild, injured; to have them legally in my possession is a rare pleasure.

It is not commonly known, but hawks smell.

After her accident, the female sparrowhawks breath became a mixture of metallic sour fish and ammonia; a rancid, tacky odour that remained on my skin and in my nose. The male, cooped up and cloistered from the world, had lost his lustre, had the stale rot of forced captivity.

All hawks have a protective sheen, a bloom, weather-proofing against the rain. A fresh bloom on a hawk with perfect feathers is divine. The detailed rehabilitation of each hawk complete, they now emit a low, musty tang, the smell of soft earth, rotting peaches, the marmalade mossiness of dried twigs. Anything that smells this good is undeniably fit and ready to go free.

The rehabilitation and release of these sparrowhawks is the penultimate stage and culmination of an obsessive journey a journey that sent me in search of a visceral and unmediated relationship with the natural world. One that exposed me to many profoundly moving moments. I witnessed golden eagles soaring from monolithic granite mountainsides, over Austrian castles and across the blizzard-streaked landscapes of Germany and northern Europe. In temperatures of minus 32C, near the Sioux Indian reservations of South Dakota, a tiny speck, a trained falcon, looped over, stooping hundreds of feet. At extreme velocity she sliced across a pheasant, sending it wheeling and tumbling to the ground, as descending blood froze in beads and pomegranate-red flesh was cast across snow. In the hazy heat of a Croatian summer dawn, I saw the speeding smear of a wild sparrowhawk chasing coturnix quail into an azure sky, scattering them in a mottled brown explosion of little clockwork fireworks. In ripping cross winds, and the harsh winter of South Dakota, I witnessed the most powerful falcon of all. A rare, wild, almost black, melanistic gyr falcon, a silhouette of wraith-like proportions, set against the reflective silver ripples of a vast lake. In Texas I followed a family unit of wild Harris hawks. Shrewd and cunning pack hunters, they scudded after rabbits through the desert scrub where pale sand meets turbulent sea on the Gulf of Mexico. It was also in Texas that I trapped a diminutive American kestrel. Shoulders cobalt, tail feathers metallic burnished bronze, he was brighter than a hummingbird and bit me hard before being released.

Of all the journeys I have undertaken it was time spent with the tribal falconers of Pakistan in 2007 that overwhelmingly changed my perception of birds of prey. Like all indigenous people, the tribal falconers methods have remained unchanged for many thousands of years; their form of hunting with hawks is perhaps the purest I have ever experienced. On the whole, they are poor subsistence farmers, falconry forming part of their survival. For these people, falconry is deeply ingrained within an identity, which itself is set in equal balance with their environment.

My time in their company exposed me to a way of life little known to the Western world. Despite the obvious language barriers, seemingly insurmountable cultural differences and customs, we shared, through falconry, an instant kinship, became friends and respected one another.

Some of the lessons I learnt have now been translated into the training and rehabilitation of the hawks in my cottage. The Pakistani falconers methods are ancient, evolved and so refined that on these hawks exquisitely formed shoulders rest generations of shared human history. They are perhaps the most important hawks I have ever owned. They are utterly irreplaceable, priceless in a very literal sense, and I cannot wait to set them free.

I hope I never see them again.

*

Looking back, it seems inevitable that I would be a falconer.

As a child, our household had respect for different races and cultures, and stories of travel pervaded our lives. In his youth, my father followed the hippy trail through Europe and down into India. He travelled to America and also worked for mining companies in the outback of Australia. He kept mementoes of his travels in a huge oak chest. I would climb inside and spend hours touching and looking at these strange, otherworldly objects: fossilized wood, a desiccated puffer fish; a spiky ball of pale tan and tinted yellows; a dingos canine tooth; coins; beads; wooden totems; and numerous black-and-white photographs. One image remains in my mind to this day. Standing in a desert, two lithe young men hold a pair of protesting eagle chicks their wings are pulled apart by the men and extend to waist height.

My mother and fathers approach to parenting was non-conformist, libertarian and not without turmoil. All rules were fluid, fluctuating on a whim, practical jokes common. They once convinced me I had the power to lay eggs. A nest was built and I was encouraged to sit and wait for one to arrive, like a broody, five-year-old human/hawk hybrid, dressed in a pair of Spiderman underpants. I can still feel the tense curl of expectation in my stomach. The inevitable disappointment was huge.

Our cottage was situated deep within the English countryside. Exposed to nature at an early age, artistic and creative, I lived in my imagination or in the outdoors. I built numerous dens and hideouts, weaving wood and leaf litter, cutting and creating my own world in the process. I made fire, would hunt and trap animals. I taught myself to tickle brook trout, whipping them out of water by hand. Once they had been gutted, I flash-fried them for lunch. In the spring and summer, slowworms, newts, frogs, toads and gallons of tadpoles ended up in buckets. I threw stones at a hornets nest, and big brutal insects spilled into the sky in a massed ochre cloud, the buzzing tone dangerous and low. I tied daddy-long-legs into cotton thread, flying them high into the sky, before winding them back to the ground, joyfully repeating the process for hours. An injured mole, cleverly kept and watched in a metal box, was fed worms I dug from the garden. Unable to keep up with her voracious appetite, I eventually released her. I clearly remember her soft silver coat and fat, pink-paddle hands as she swam back beneath the soil. Numerous tennis-ball-sized baby rabbits arrived on the floor and doorstep. Some survived, others succumbing to the stress and mess and the cats jaws. On a low winter afternoon, alone among snow-stripped saplings and bare trees, a muntjac deer screamed. In front of me on the floor, an isolated, trident-shaped footprint. A head full of my own fantastic stories and the strange noise of the deer, I knew for certain it was a monster. I panicked and ran. Overly inquisitive and without an active idea of cause and effect, I dipped my hands into the depths of a fallen tree. I removed a palm-sized baby squirrel; it was cold, almost lifeless. To raise its body temperature, I tucked it into the only thing warm enough, my sweaty plimsoll. I ran the half a mile home barefoot, scuffing and blistering my feet. Later I fed her cows milk but failed to keep her fragile life from slipping away. From the long grass in our garden, I borrowed twenty grey partridge chicks from the nest of their strutting, calling mother. Each was the shape and texture of a bumble bee, and I built them a new home across my duvet, using a hairdryer to keep them warm. Once discovered, they were boxed up and driven to a member of the local shoot, to be raised, released then shot: the oddest parental logic. Smaller birds were a better prospect, some fallen from nests, others brought in by the cats. I raised one by hand; it would perch indoors on the curtains, flying across the front room for worms and hand-held maggots and was a potent shape of things to come.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Blood Ties»

Look at similar books to Blood Ties. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Blood Ties and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.