Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by Ray E. Boomhower

All rights reserved

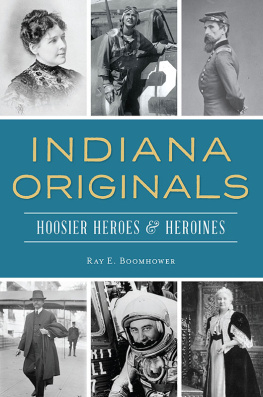

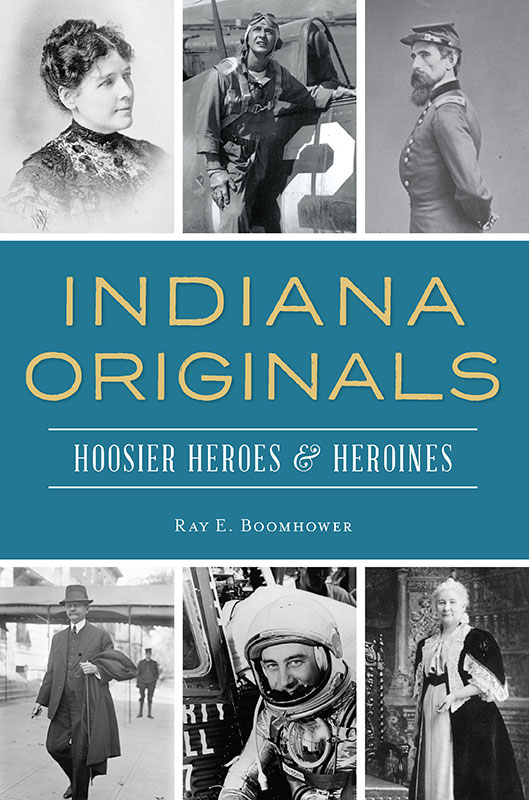

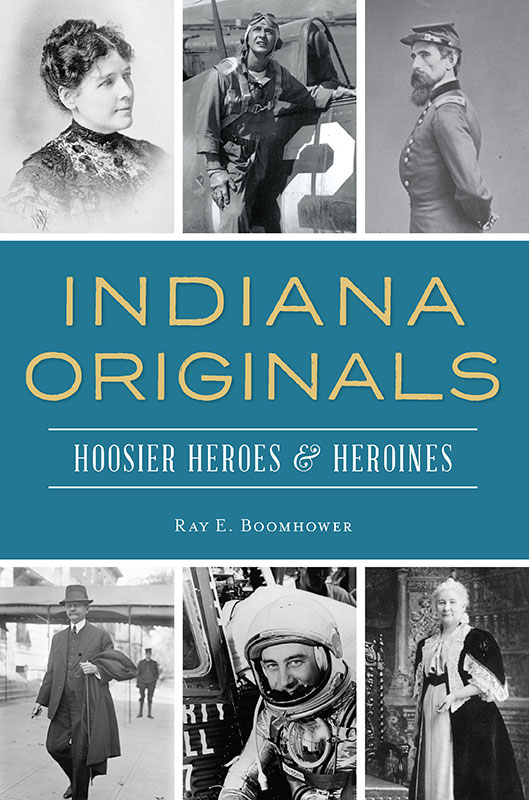

Front cover, top, left to right: Juliet V. Strauss. Courtesy Cynthia Snowden; Alex Vraciu. Courtesy Alex Vraciu; and Lew Wallace. Indiana Historical Society, M0292. Bottom, left to right: Thomas R. Marshall. Library of Congress; Virgil I. Gus Grissom. National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and May Wright Sewall. Library of Congress.

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.46714.097.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948035

print edition ISBN 978.1.43966.575.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Good editing has saved bad writing more often than bad editing has harmed good writing.

Gardner Botsford

To all the editors with whom I have had the pleasure of collaborating with over the past thirty years: J. Kent Calder, Thomas Mason, Paula Corpuz, Kathy Breen, George Hanlin, Rachel Popma, Teresa Baer, Linda Oblack, Sarah Jacobi and Ashley Runyon. Most of all, to my wife, Megan McKee, whose opinion has mattered above all others.

Contents

Preface

In her book Biography: The Craft and the Calling, Catherine Drinker Bowen, who in her career examined the lives of such figures as Tchaikovsky, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., John Adams and Francis Bacon, states that the biographers aim is to bring to life, persons and times long vanished. He [the biographer] has a conception of his hero which he desires to share; he cannot bear that this man should be forgotten or exist only in dry eulogy or brief paragraphs of the history textbooks. David McCullough, the author of bestselling biographies of such American notables as Theodore Roosevelt, Harry Truman and John Adams, agrees with Bowens assessment but adds that a biographer must genuinely care about his subject.

Both of these legendary writers offer sound advice for the budding biographer. But what is it that inspires someone to partake in the long, painstaking process of digging into a persons life? In my case, I have to take you back to the year 1967. At that time, I was in the third grade at Mary Phillips Elementary School in Mishawaka, Indiana. I had as my teacher a young woman named Patricia Swarm. For some reason, perhaps because of my gap-toothed grin or bizarre haircut inflicted on me by a rookie barber, she took an interest in me, particularly my growing love of reading. Although other teachers might have scolded me for reading ahead in the text during a classroom assignment, Miss Swarm noticed my enthusiasm for the printed word and encouraged me to read whatever interested me. In my case, this happened to be any book on history or biography.

My favorite room in the school quickly became the small library, located on the ground floor. The library featured such state-of-the-art equipment for the time as a record player with earphones, which I used extensively to listen to a National Aeronautics and Space Administration album filled with the sounds of the American space program. I became entranced at the exploits of those early space pioneers and vowed to become an astronaut myselfa dream killed by my fear of heights and low scores in mathematics.

My favorite spot in the library, however, occupied a spot just off the rooms entrance: a bookshelf filled with biographies about the childhoods of famous Americans, a series of books released by the Bobbs-Merrill publishing firm in Indianapolis. Today, more years later than I would like to admit, I can still recall details from those charming tomes, including Lou Gehrig hunting eels with his mother in New York City, a young Andrew Jackson standing up to a British officer during the Revolutionary War and Babe Ruth pitching for his baseball team from the Saint Marys Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore, Maryland.

The Bobbs-Merrill series sparked my lifelong interest in history, which in turn led me to where I am todayan author who over the past three decades has published numerous books and articles about the Hoosier State, the majority of which have been biographical in nature. None of this would have been possible, however, without the encouragement of a dedicated teacher. In some way, I think, I write about history in order to pay back Miss Swarms kindness to her young pupil.

In their book After the Fact, historians James West Davidson and Mark Hamilton Lytle advise their readers that when historians neglect the literary aspect of their discipline, when they forget that good history begins with a good story, they risk losing the wider audience that all great historians have addressed. In my more than three decades working at the Indiana Historical Society, I have been able to indulge my love of biography by writing good stories for the IHSs popular history magazine, Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, as well as having the thrill of being published in Outdoor Indiana magazine and the scholarly quarterly Indiana Magazine of History. I have turned some of those articles into book-length manuscripts published by IHS Press, the former Guild Press and Indiana University Press.

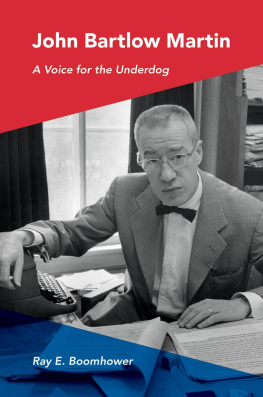

In this book, you will find a collection of pieces I have written over the years. They cover a wide fieldthe wit and wisdom of a cracker-barrel philosopher, the courage of a war correspondent and combat photographer under fire, the dedication of a peace activist during wartime and the harebrained schemes of an automotive pioneer, as well as the dedication of a freelance writer championing the underdog in American society. The stories, however, have two common themes: they are about Hoosiers and deal with bringing an individuals tale to life for a reader.

Biography, as one of my subjects, John Bartlow Martin, once said, brings with it many difficulties:

Too much detail will bore the reader, too little will disappoint him. To what extent should the author act as an advocate of his subject? To what extent a critic? How is he to make his subject come alive, to breathe? How can he answer the terrible question: What made him the man he was? How much of his private life as well as his public life to include? What, aside from the laws of libel and invasion of privacy, sets limits? Taste? But whose taste? The biographers obviously; but this is a grave responsibility.

A grave responsibility, indeed, and one I have tried to take seriously. Writing lives may very well be the devil, as Virginia Woolf once claimed, but it also is a lot of fun.

Creator of Abe Martin

Frank McKinney Kin Hubbard

Irvington, a planned community on Indianapoliss east side, has been home to a number of famous Hoosiers through the years. One day in the 1910s, a camera-laden tourist was searching through the area for the home of Frank McKinney Kin Hubbard, the creator of cracker-barrel philosopher Abe Martin, whose folksy brand of humor graced the Indianapolis Newss back page for twenty-six years.

Finally finding Hubbards home, the visitor approached a disheveled-looking gardener working on the authors lawn and asked him if he thought Mr. Hubbard would mind if he took a few snapshots of the house.

Next page