All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

CROWN is a registered trademark, and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Lunde, Darrin P.

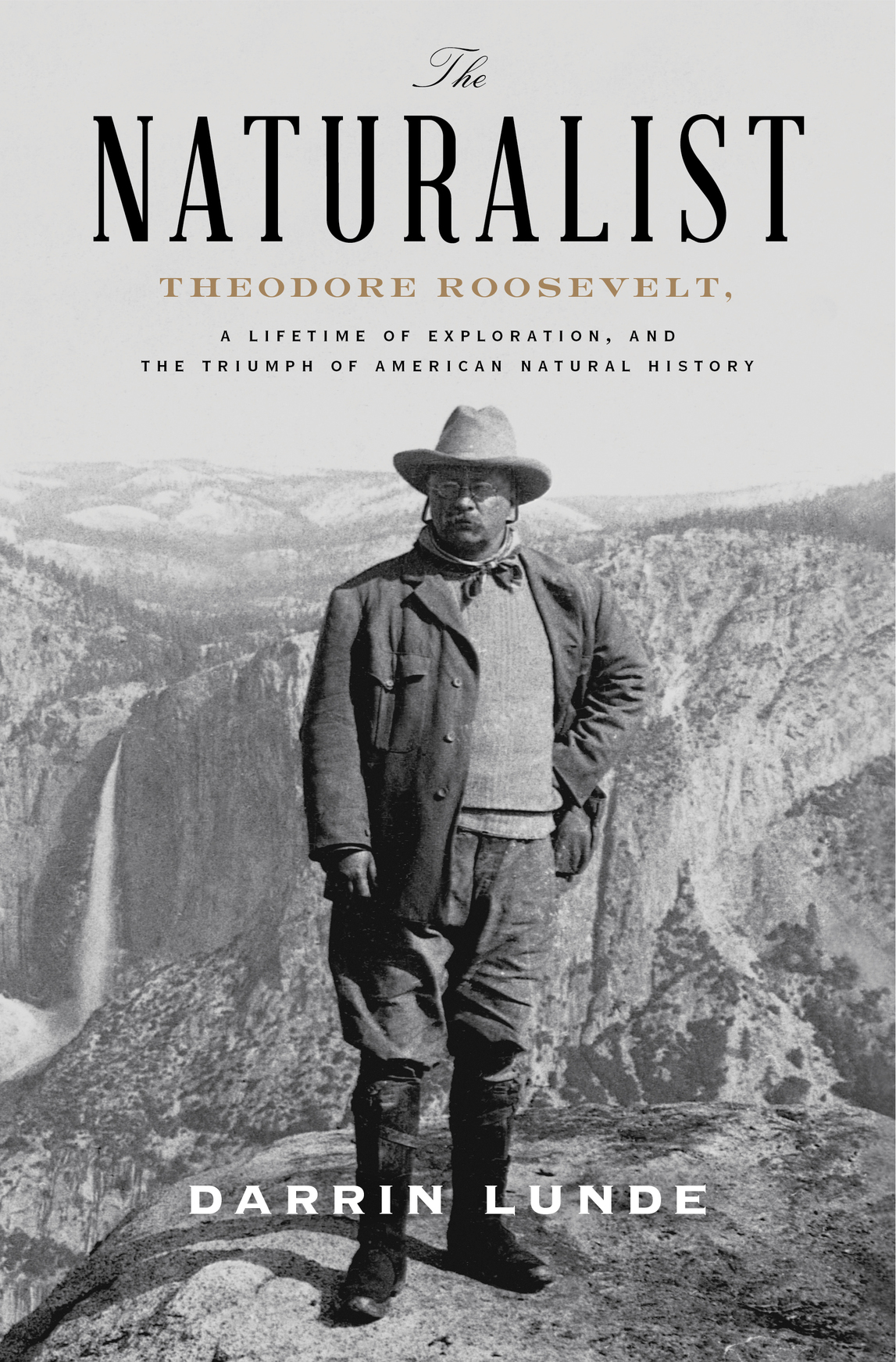

Title: The naturalist : Theodore Roosevelt, a lifetime of exploration, and the triumph of American natural history / Darrin Lunde.

Description: First edition. | New York : Crown, 2016.

Subjects: LCSH: Roosevelt, Theodore, 18581919. | Nature conservationUnited States. | Natural history museumsUnited States. | NaturalistsUnited StatesBiography. | ConservationistsUnited StatesBiography. | PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Presidents & Heads of State. | NATURE / Animals / Wildlife.

Imagine whats behind a closed door in a natural-history museum. Back rooms lined with jars of snakes in alcohol, a vault full of hippo skulls, an attic of elephant bones. Rooms stacked with thousands of stuffed birds, basement vats of alcohol-preserved gorillas, or a closet of tanned zebra hides. All these things are hiding from museum patrons, beyond exhibitions and displays. This is the unseen world of a natural-history museum, awash with scientific specimens. Stuffed, skeletonized, or preserved whole in jars, nearly all these animals were collected by museum naturalists.

Millions of these specimens will never be displayed; the public will never see them. Instead, they are collected for scientific study, which is essential to understanding the worlds great diversity of life. Every known animal speciesevery bird, mammal, fish, frog, and snakewas named based on museum specimens. Virtually everything we know about the morphology, geographic distribution, and ancestral relationships of animals is derived from the vast collections of specimens housed in museums. Natural-history museums represent our record of life on Earth.

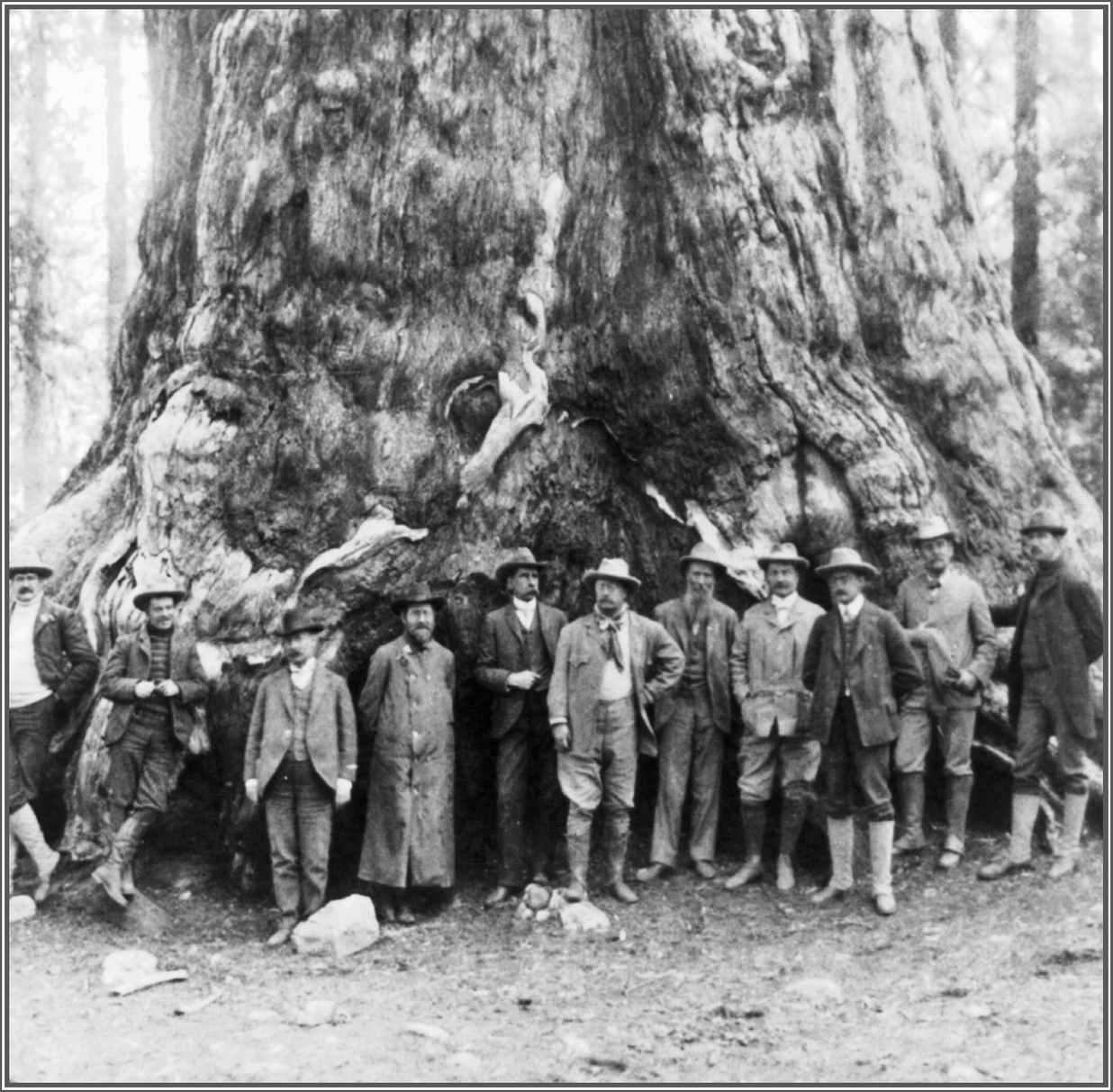

Some of these rooms may have been partially filled by Theodore Roosevelt, who (among many other things) was an intrepid museum naturalist. From early childhood through his years in the White House, Roosevelt studied animals by shooting them, stuffing them, and preserving them in natural-history museums, and we should be thankful he did. One of the countrys greatest museumsthe American Museum of Natural Historywas founded in his living room when he was just a boy. He lived in an age when natural-history museums commissioned scientists to explore and document uncharted terrain, collecting specimens for both study and exhibit. Whether sent to the deepest jungles of central Africa, the high Himalayas, or the deserts of the American West, these museum naturalists camped out in the remotest parts of the world for weeks and months at a time. They slung guns over their shoulders and fought their way into the last unknown regions of the world, all in the name of zoological exploration. Part scientist, part explorer, they collected animals by the thousandand, for such a naturalist, collect meant kill and preserve, a fact easily forgotten today.

From a very early age, Theodore Roosevelt devoted a great deal of his energy to building up his own natural-history collection. He was seduced by the challenge of collecting something rare. Although hunting birds and mammals for science has a higher purpose (natures mysteries are best revealed with a dead specimen in hand), for Roosevelt, collecting specimens also satisfied his desire for adventure.

Museum naturalists might be thought of as hunters for science, their trophy rooms the vast collections housed in natural-history museums. Despite the size of their stores, the collections of these institutions arent limited to taxidermy exhibits. More valuable to scientists are museum study skins, prepared to be densely packed in rows of cabinets full of drawers. Bird specimens lie breast up, their wings tight against the body, and bill pointing forward. Mammal specimens lie prone, arms and legs extended, their cleaned skull in a box or vial set to the side. Museum study skins represent a compromise: they are stuffed so that they show all the external features of the animals, but in a way that will allow many examples of the same species to be stored neatly and compactly behind closed doors.

Museums put their specimens in taxonomic order, meaning one can walk down an aisle of cabinets to browse through similar species of a kind. There might be a long run of, say, voles in the rodent section of a collection, and opening drawer after drawer would gradually reveal the many different species of volespine voles, red-backed voles, prairie voles, and so oneach species distinguished by particular traits.

The real value of all these collections, and the thing that drives any zoological collector to want to gather more specimens in the field, is posterity; these collections are kept in perpetuity, providing a historical record of past expeditions while at the same time documenting biodiversity. Wandering the various storerooms of such a museum is like traveling around the world, thanks to the efforts of what probably amounts to thousands of years of cumulative human effort in assembling these collections from every corner of the globe.

Museum specimens are traditionally identified by a paper tag attached to the preserved animals leg. Often yellowed with age and annotated in tight cursive, the tag gives the precise location of an expedition, the exact date the animal was trapped or shot, and the name of the naturalist who captured it. Thus, the collector is forever tied to his specimens. But who were these early museum naturalists? And why was Theodore Roosevelt so inspired by them?