THE PRESIDENT AND THE PROVOCATEUR

feralhouse.com

OTHER BOOKS BY ALEX COX

10,000 Ways to Die: A Directors Take on the Spaghetti Western X Films: True Confessions of a Radical Filmmaker

The President and the Provocateur

Alex Cox 2013

Editor: Carrie Schaff

Typeset by Elsa Mathern, in Ionic 8.5pt

A Feral House Original Paperback

All rights reserved.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-1-93623-963-4

feralhouse.com

Feral House

1240 W. Sims Way Suite 124

Port Townsend WA 98368

This is dedicated to Mark Lane

CONTENTS

The memory carried him to another: how, when he had traveled in the big cities and the crowds had lined the sidewalks, and overspilled into the roads, he could look up to the windows of the office buildings and there, above the cheering street mobs, see the white-collared executives staring down at him. And in city after city, as if by common instinct, they were all giving him the universal bent-arm, clenched-fist gesture of contempt and formally forming on the lips a curse that he could read above the shouting.

Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1960

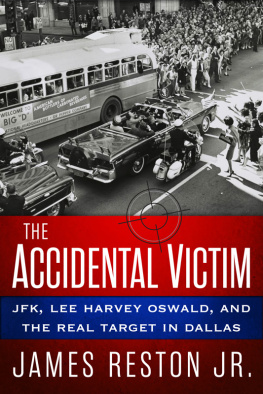

Kenneth ODonnell, friend and associate of President Kennedy, [said] on the morning of November 22, 1963 the President remarked to him and Mrs. Kennedy that If anybody really wanted to shoot the President of the United States, it was not a very difficult joball one had to do was get on a high building some day with a telescopic rifle, and there was nothing anybody could do to defend against such an attempt.

Anthony Lewis, On The Release of the Warren Commission Report

The story which follows takes place in the mid-twentieth century.

While some of these events remain vivid to people still alive, for most of us, these are old, somewhat legendary occurrences, subject to controversy, which happened a long time ago.

I was eight years old when President Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald were murdered. Id only the vaguest idea of America as the place where comic books came from. We did not live in a media-rich environment in 1963. My parents read a right-wing national paper, the Daily Mail, and our local rag, the Liverpool Echo, which contained one American comic strip, Flash Gordon. There was no such thing as 24-hour TV, no Internet, no cable, no satellite broadcasting. Instead there were two TV channels, broadcasting in black and white for about six hours a day. There were some schools broadcasts in the afternoon, but otherwise TV kicked off around 5 p.m., and shut down well before midnight. Nevertheless, what happened on November 22, 1963 was singularly strange. My family was gathered in the front room, to watch a popular comedian, Harry Worth, in his scheduled weekly show. Instead, the news of the presidents murder was announced, and then the broadcast ceased.

This was before the days of rolling news but the assassination of John Kennedy was a live, breaking news story of enormous importance: perhaps the most important piece of news since the end of the Second World War. For the BBC to go off the air in this way seemed strange. This President Kennedy was apparently an important man, his murder a matter of significance. So why were we staring at a black screen?

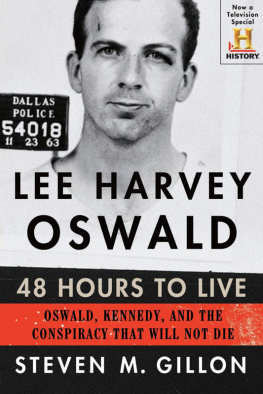

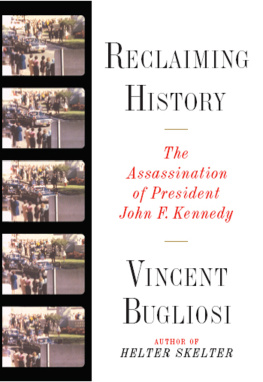

BBC television stayed off the air for several hours. The next day, the news was that a suspect had been arrested. The day after that, we learned the suspect had been killed in custody. The new president, in whose home state Kennedy had been assassinated, set up a blue-ribbon panel to investigate the murder. The panel, named the Warren Commission after its chairman, the chief justice, declared that Lee Harvey Oswald was the murderer, and that he had acted alone.

So that was that. What I didnt know at the time (because these things were never mentioned by the BBC, or the Daily Mail, or the Liverpool Echo) was that a number of prominent figures in England were skeptical about this official story. Britains most eminent philosopher, Bertrand Russell, her most famous historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, the politician Michael Foot, the publishers Victor Gollancz and John Calder, the authors J.B. Priestley and Compton Mackenzie, and the film director Tony Richardsonamong othersset up a Who Killed Kennedy Committee. It was ignored by the media; nothing came of it. Looking back on my childhood, I think there must have been a statewide effort to purge the presence of Russellan atheist, a pacifist, and a freethinkerfrom the national mind. Religion was enforced within the English school system, and while at grammar school I read his History of Western Philosophy; but I had no idea that Russell was also the author of an excellent pamphlet entitled Why I Am Not A Christian. And I certainly didnt know that he and other eminent Britons had challenged the official version of the Kennedy murder.

Around the age of 15, I encountered in a bookshop a Jackdaw about the assassination. Jackdaws were pretty cool aids to education. They were folders containing reproductions of historical documents: for example, the one on the English Civil War containing writings by Cromwell and the death sentence of the King. Unusually, this Jackdaw was full of contemporary material.

It was put together by the author Len Deighton, based on Mark Lanes best-selling book Rush to Judgment. It contained the WANTED FOR TREASON handbill distributed prior to the presidents murder, a selection of autopsy photographs, andmost wonderful of alla cardboard model of Dealey Plaza, where the assassination had occurred. Once you had constructed the little cardboard buildingsthe Texas School Book Depository, the Dal-Tex Building, and the County Records Officeyou could with strands of cotton plot the trajectories of the hail of bullets which killed the president and wounded the Governor of Texas. Your attention was naturally drawn to the railroad overpass, which offered limitless scope to a concealed assassin, and to the celebrated Grassy Knoll.

(Though we didnt know it at the time, the American Embassy in London, disturbed by Hugh Trevor-Ropers involvement in the Who Killed Kennedy Committee, asked FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to respond to an article the historian had written. Hoover refused, so the Embassy arranged for a friendly press sourceJohn Sparrow, later Warden of All Souls College, Oxfordto write an article defending Hoover and the Warren Commission. Airtels from Legat, London to the FBI director give the impression that the American Embassy was running Sparrow. When Mark Lane challenged him to a debate in

An incipient conspiracy theorist, I read Rush to Judgment, an impressive work of investigatory scholarship which derailed the Warren Report. Over the next forty years I spent a lot of time learning about the subject. I subscribed to journals, including

Next page