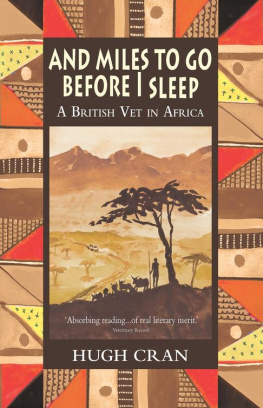

Hugh Cran - And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa

Here you can read online Hugh Cran - And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: Merlin Unwin Books, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa

- Author:

- Publisher:Merlin Unwin Books

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hugh Cran: author's other books

Who wrote And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost

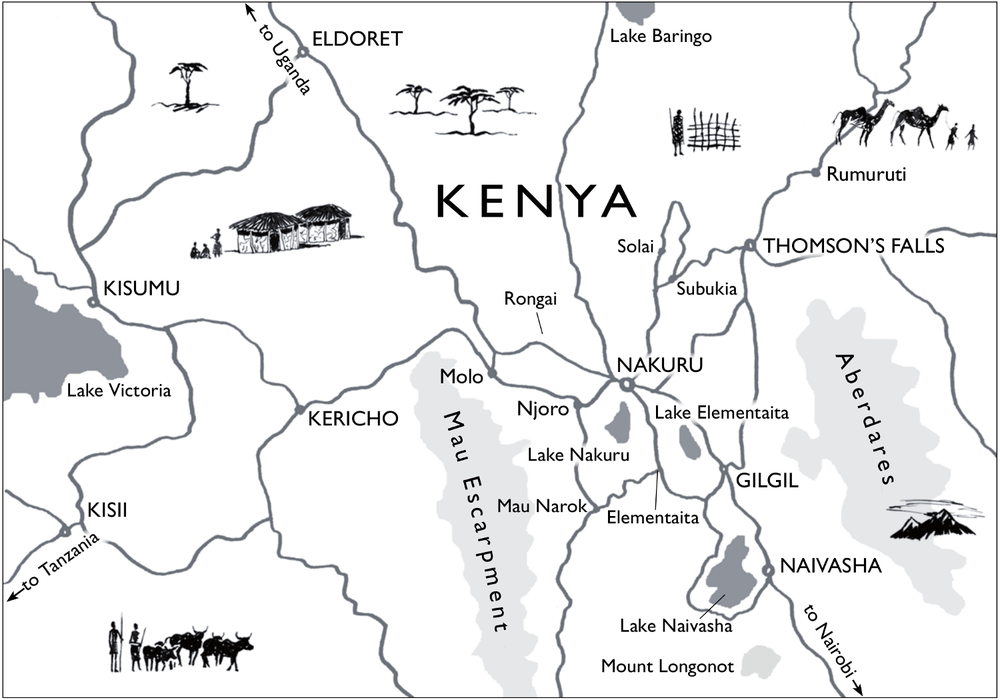

In early December in the Year of our Lord 1966, while Britain lay blanketed in snow and darkness I boarded an East African Airways jet and was flown in moderate discomfort from London to Nairobi.

I had never flown before and perhaps it was fortunate that I hadnt, as the novelty of the experience had the concentrating effect of preventing me from brooding on whether I was really doing the right thing. I knew that most people back in Scotland thought I was mad to be going off to the land of the Mau Mau, to a country hissing with man-eating lions, gin-swilling colonials and machete-swinging natives, abandoning a solid, safe career in solid, safe Scotland, not to mention the wilful desertion of my recently widowed mother, left to fend for herself in the wilds of Edinburgh.

I told people that I was only going for a trial period, perhaps a year at most, just to test the waters. They laughed. They were right to laugh it was to be eleven years before I saw the grey roofs and jagged skyline of Edinburgh again.

I was 26 and single, and, for the past three years I had, since graduation from the Royal Dick School of Veterinary Studies in Edinburgh, worked as an assistant veterinary surgeon in a large-animal practice in the north-east of Scotland. The land was bleak, treeless and windswept. The people were equally bleak and windswept, suspicious of strangers, although hospitable and kind in a dour and introspective way. The winters were hard and cold with icy winds and heavy falls of snow which often lay for weeks before melting. Sometimes when going out to a distant farm on a winters night, when the snow lay deep and banked in the fields and the wind was blowing and the snow ploughs not out, I could not be sure of returning before dawn as the roads filled with snow behind me. Then I had to spend the night in my freezing car or seek refuge in a farm-house.

Winter and summer the leaden cloak of the lowering sky seemed to sink ever closer to the brooding earth until, by the time I left, I felt I could almost touch it. In their squat cottages, the present-day Picts sat and supped their porridge. I liked porridge, but I hankered after a slice of paw-paw for breakfast. Stocks of fresh paw-paw were scant in rural Aberdeenshire and I would have to venture forth if I were to find some.

But the work was rewarding and my employer and other colleague in the practice were of inestimable value in consolidating my knowledge and furthering my experience. Sheep, pigs, dogs, cats and black Angus cattle made up the bulk of the animals in the area. During the lambing season, hundreds of visits would be made to farms to attend to ewes or their lambs. The workload was heavy and demanding; the experience gained, invaluable.

The thought of practising tropical veterinary medicine had, however, for a long time lain dormant in my mind and, after an offer of a post as a veterinary officer in Uganda had fallen through because of a lack of funds, I applied for a job in a practice a hundred miles from Nairobi. After a brief correspondence I was on my way. No interview, no phone call, just a couple of blue see-through aerogrammes and that was it. The job was mine.

The plane flapped and rattled through the night. It made an unexplained detour to Rome presumably to refuel. I studied my fellow-passengers , of which there were few the plane was half empty. Apart from a couple of pallid tyros like myself, the rest were a mixture of well-dressed Africans, turbaned Asians and sunburnt Europeans. To my ingenuous eyes the latter looked distinctly bizarre, especially as it had been snowing when the plane left London. The men were wearing khaki, sleeveless bush jackets sporting dozens of bulging pockets containing I knew not what. Their wrists were hidden beneath copper bangles, wiry bracelets which I later learnt were made from the hairs of an elephants tail, and the sort of beaded things I imagined might look better on a Maasai warrior. The women were raw-boned, sun-bleached and rather less flamboyant than the men. I fervently hoped that they were the exception rather than the rule as far as white Kenyan females were concerned. My visions of Ava Gardner look-alikes in damp linen slacks slinking through the bush had taken a bit of a knock.

My preparations for life in the tropics had been scant. A shot against yellow fever, a vague directive from the quack about malaria and that was it. My wardrobe was even more destitute and had nothing in it at all suitable for the tropics. Shorts were not on the shelves in Aberdeen in December, and Ambre Solaire was not an item in much demand in the north of Scotland at any time of year, let alone mid-winter. Sartorially and medically I was singularly ill-equipped.

My African experience was limited to student trips to Morocco, and Algeria during the last frantic years of the French occupation. Once again I had the disturbing feeling that I was an innocent abroad.

The thoughts which passed through the brain of my future employer as he penned his advertisement will never be known, but it can plainly be stated without fear of contradiction that they were not of a philanthropic or benevolent nature. A large man of about sixty, supporting a well- established paunch, his prominent blue eyes glared aggressively and resentfully at the world around him. To compare his bald dome with that immortal structure built by Sir Christopher Wren would be to cast a monumental slur upon the latter.

I arrived at the old Embakasi airport soon after dawn and, having passed through customs, scanned the crowd for Arthur Owen-Jones, my new employer. He found me, probably recognising me as a new boy to Africa by the pallor of my epidermis and by the fact that my nether limbs were encased in grey flannel trousers. Old Africa Hands tend to wear shorts, an open-necked shirt, safari boots, and are burnt by the sun to the colour of lightly-done toast, the lot being surmounted by a well-bashed and fairly shop-soiled bush hat. Owen-Jones broke all of these rules, despite the fact that he had been living in Nakuru, the former capital of the White Highlands in the Great Rift Valley, for over eight years. He wore a loud checked shirt, his cavalry twill trousers were suspended by a pair of braces, on his feet he wore a pair of elastic-sided boots, while his bald head, exposed to view, shone in the rays of the early-morning sun now streaming through the plate-glass windows of the airport.

After establishing identities and after Owen-Jones had enquired as to whether I was suffering from anaemia, we repaired to the Simba Grill, on the second floor of the airport, for breakfast. Just below the window stood a flat-topped acacia, the archetypal tree of East Africa. The Athi Plains stretched away, grey and brown, to the horizon.

During the course of the meal, Owen-Jones berated the waiter in what I later learned was execrable Swahili but which seemed to my then untutored ears to be a fluent rendering of an exotic African tongue. Delivered in a loud Welsh accent, Owen-Jones seemed to derive much satisfaction from this, and, belching contentedly, settled back in his chair.

Following the meal, I collected my unaccompanied baggage from the customs shed. It included my climbing gear ropes, ice-axe, crampons and boots. Having done some mountaineering in Scotland and the Alps, I hoped to be able to pursue my hobby, in a modest way, among the mountains of East Africa. I shouldered these items with what I hoped was a nonchalant air, but the smirks and mocking grins cast in my direction by other baggage collecting passengers suggested that I was not altogether successful in my endeavour. I loaded my things into Owen-Jones Peugeot 404 station-wagon and we set off.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa»

Look at similar books to And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book And Miles to Go Before I Sleep: A British Vet in Africa and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Robert Hugh Benson [Benson - Robert Hugh Benson Collection [11 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/139831/thumbs/robert-hugh-benson-benson-robert-hugh-benson.jpg)