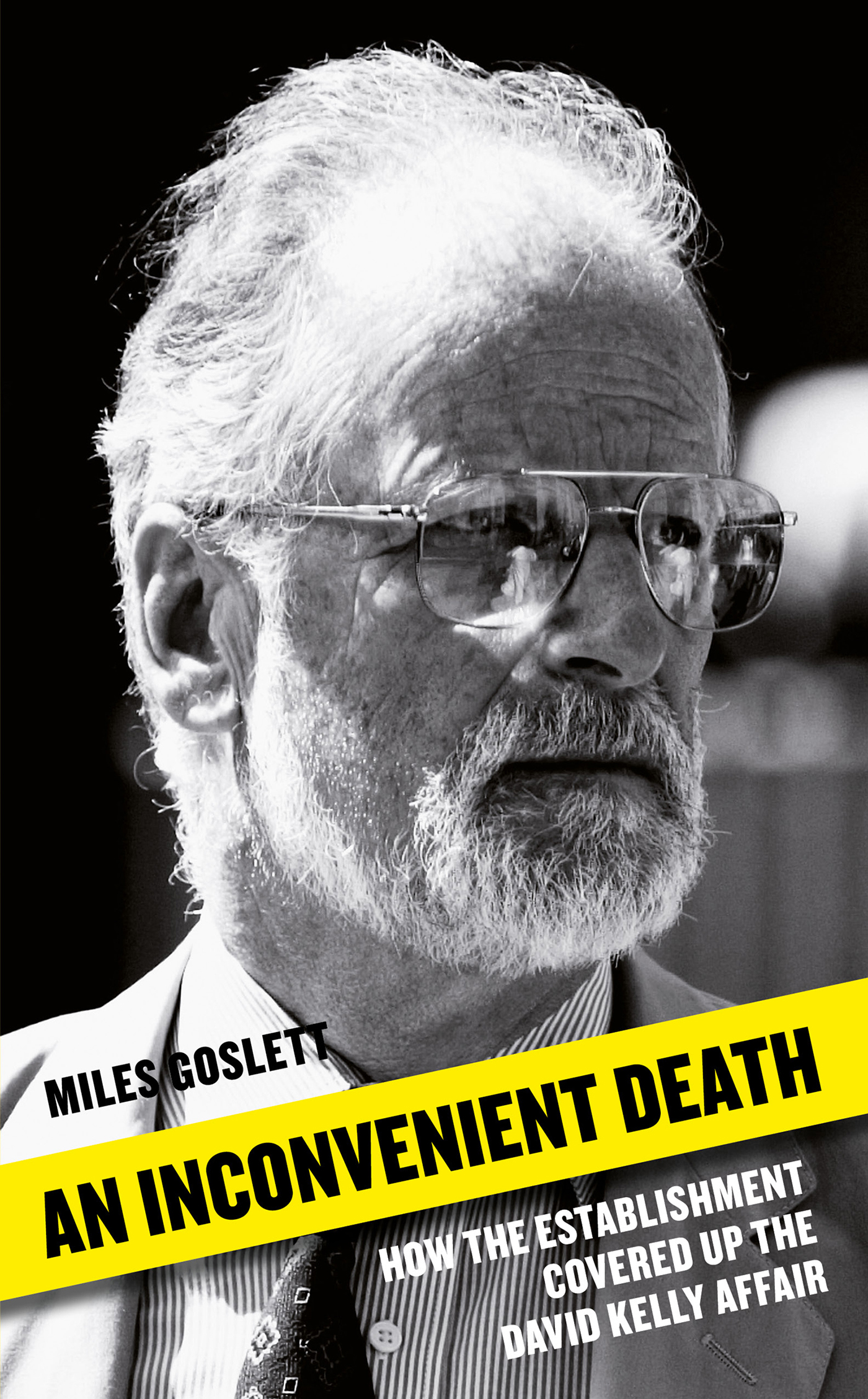

AN INCONVENIENT DEATH

How the Establishment Covered Up the David Kelly Affair

Miles Goslett

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

THE DEATH OF DR DAVID KELLY

In 2003 is one of the strangest events in recent British history. This scrupulous scientist, an expert on weapons of mass destruction, was caught up in the rush to war in Iraq. He felt under pressure from those around Tony Blair to provide evidence that Saddam Hussein was producing weapons of mass destruction that could be used to immediate and devastating effect. Kelly seemed to have tipped into sudden depression when he was outed as a source for Andrew Gilligan. Case closed, for Blair, Alastair Campbell and the intelligence agencies.

But the circumstances of his death are replete with disquieting questions every detail, from his motives to the method of his death, his bodys discovery and the way in which the state investigated his demise, seems on close examination not to make sense. There was never a full coroners inquest into his death, which would have allowed medical and other evidence to be carefully interrogated.

In this painstaking and meticulous book, Miles Goslett shows why we should be deeply sceptical of the official narrative and reminds us of the desperate measures those in power resorted to in that feverish summer of 2003.

Contents

Shortly after 3 p.m. on Thursday, 17 July 2003, Dr David Kelly left his house in the Oxfordshire village of Southmoor to go for one of his regular short walks. He had changed into a pair of jeans, put his house key in his pocket, and tucked his mobile telephone into a pouch on his belt the routine actions of a man preparing to do something he had done many times before.

His wife, Janice, had retired to bed two hours earlier because she felt unwell. He didnt say goodbye to her or leave a note.

Within fifteen minutes of setting off, he bumped into a neighbour who was walking her dog. They exchanged a few pleasant, unremarkable words. She then saw him stroll down the road as she turned for home. She was the last person known to have seen Dr Kelly alive.

Back at the house, Mrs Kelly had recovered sufficiently to go downstairs. When her husband failed to return after a couple of hours she began to feel some unease, but she did not try to ring his mobile phone. Instead, she waited until she was able to share her growing concerns regarding his whereabouts with her youngest daughter, Rachel, who had arranged to meet her father that evening so that they could go for a walk together.

On hearing the news, Rachel decided the situation warranted some kind of action. First on foot and then in her car, she began tracing the routes that she knew Dr Kelly habitually took. She also contacted her sisters, one of whom was prompted by Rachels call to drive seventy miles from her house in Hampshire to join in what was still just a family search. Despite hours of looking, neither daughter found him.

At 11 p.m. the two women went back to their parents house and, with their mother, debated what to do next. Shortly before midnight, they decided they must contact the police to report him missing. By this point, Dr Kelly had not been seen for almost nine hours.

This was the relatively low-key start to an overnight hunt that would involve more than forty police officers, a police dog, a police helicopter, plus some volunteer searchers, with a mounted police unit and an underwater police search team also being called upon. In the early hours, Metropolitan Police officers from Special Branch were told to search Dr Kellys London office, and senior figures in Whitehall were alerted to his disappearance.

Such an operation, launched so quickly, might have been expected for a top public figure, but Dr Kelly was officially, at least a mere civil servant.

Just after 9 a.m. on Friday, 18 July, two volunteer searchers helping the police found a body matching the description of David Kelly in a wood at Harrowdown Hill, about two miles from his house.

At the time the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, was on a plane travelling between Washington DC and Tokyo. The Lord Chancellor, Charles Falconer, who was in London, rang Blair on the aircrafts phone within minutes of the body being found and in a surprisingly brief call was instructed to set in motion a full-blown public inquiry into Dr Kellys death.

Falconer established this inquiry several hours before any exact cause of Dr Kellys death had been determined officially and, indeed, before the body found that morning had even been formally identified.

What could possibly have led Falconer and Blair, the two most senior political figures of the day, to take this unusual step on the basis of what, according to contemporaneous police reports, appeared to be a tragic case of a professional man ending his own life? Why were they even involved at such an early stage in what was essentially an incident that was local to Oxfordshire?

What was it about the death of David Kelly that had disturbed Falconer and Blair so much that they went on to interrupt and ultimately to derail the coroners inquest, which had been opened routinely? And why were they content to replace that inquest with a less rigorous form of investigation into Dr Kellys death?

These questions preoccupied me, as a journalist, for years. They pointed to powerful forces working against the proper investigation of an unexpected event in this case, a death mired in mystery.

Then, on 5 November 2014, I heard that a senior civil servant working in the Ministry of Justice had written an extraordinary letter to a man called Gerrard Jonas, a garage owner from Oxfordshire, urging him to stay away from Dr Kellys grave. The letter noted that Mr Jonas had been visiting the grave at St Marys churchyard in the nearby village of Longworth and, in a thinly veiled threat, advised him to carefully consider whether this programme is appropriate and lawful. It went on to say that a surveillance watch had been put on the grave as a result of Mr Jonass visits, though this point was worded ambiguously enough for it to remain unclear who had ordered the watch and how it was being policed. The letter was signed Barrie Thurlow, of the Ministry of Justice Coroners, Burial, Cremation and Inquiries Policy Team.

The tone of the letter certainly supported the idea that a Whitehall department and, maybe, others in officialdom still felt great sensitivity about Dr Kellys death, which had occurred more than eleven years previously. Its clear inference was that Dr Kellys grave was being monitored, perhaps by an arm of the State.

Mr Jonas whom I did not know sent me a copy of it and, being aware of my interest in the Kelly case, later rang me to explain the background to it. He said he had never met or spoken to Dr Kelly or his family; he had simply believed for many years that for reasons of public interest there should be a full coroners inquest into Dr Kellys death to establish how, where and when he had died something which successive governments have refused to allow.

To that end he had set up a group, Justice For Kelly, and on behalf of its members had written to the then Home Secretary, Theresa May, asking her to consider ordering an inquest. Mrs May had passed Mr Jonass letter on to the Ministry of Justice. Its representative, Barrie Thurlow, had replied to Mr Jonas because it was felt that the matter in question fell under his departments remit.