This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA.

E-mail:

www.shirebooks.co.uk

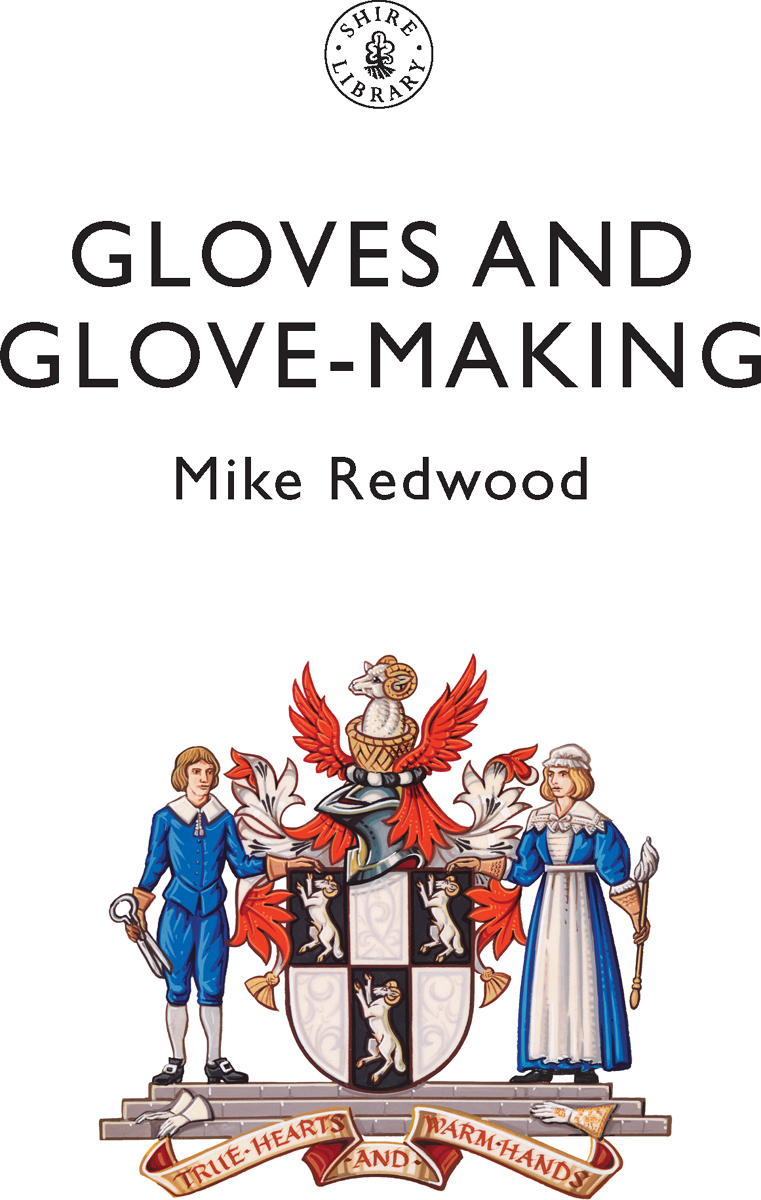

2016 Michael Redwood.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 812. ISBN-13: 978-0-74781-453-5

PDF e-book ISBN: 978-1-78442-148-9

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78442-147-2

Michael Redwood has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

Designed by Tony Truscott

Shire Publications supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations are being spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

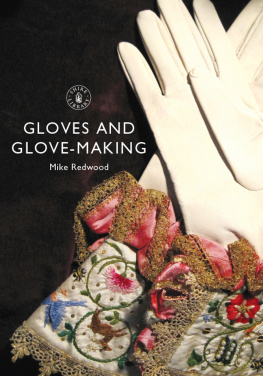

The coronation gloves of Elizabeth I (left) and Elizabeth II (right).

GLOVES SPEAK MANY LANGUAGES

Left: The Lord Chief Justice with his new gloves.

Right: Alderman Alison Gowman and members of the Court of the Glovers ready to present the gloves. The gauntlets worn by the Master remain in two parts; each year a new Master is appointed and obtains new perfectly fitting gloves for the hand and slides the historic gauntlet part over.

On 22 July 2014, the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, The Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd, was presented with a pair of gloves by Alison Gowman, the Master of the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London. The gloves were made using leather from Ethiopian hair sheep; the leather was prepared in Pittards tannery in Somerset, where glove leather has been produced since at least 1826. The gloves were hand cut and sewn by Chester Jefferies nearby in Dorset, and the cut leathers were sent to London to be exquisitely embroidered in gold thread by Jenny Adin-Christie, a Specialist Embroiderer and graduate of the Royal School of Needlework. While the names and companies have changed, this is a process that has continued for many centuries the Worshipful Company of Glovers of London itself dates back to 1349.

Top Left: Jenny Adin-Christie embroidering the gloves.

Top Right: The completed embroidery on the leather before being sewn into gloves.

Bottom: The gloves ready for presentation to the Lord Chief Justice.

Such complex and apparently old-fashioned traditions remain at the heart of British society. While the origin, use and the development of gloves is generally based around utility and protection, there has always been a strong element of symbolism and status. Gloves are objects of high fashion and were worn by the aristocracy as a mark of distinction. From the earliest of times, and most certainly since the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, no well-dressed woman would appear in public without them. There is more history, romance and legend about gloves than about any other article of clothing.

The most famous and oldest surviving pair of gloves was found in 1923 by Howard Carter and the Earl of Carnarvon in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Gloves used 3,000 years ago in Egypt would have been mostly for riding horses but were available only to the rich and powerful. These particular gloves were for the pharaoh to use for ceremonial occasions. They were of linen cloth, tapestry woven with royal and sacred emblems. The fabric was cut and sewn into gloves with bronze needles. Around the wrist were patterns of lotus buds and flowers. Gloves were loose at that time and tapes were used to tie them round the wrists, which held them firmly to the hands.

The gloves of Tutankhamun.

The role of the pharaoh in ancient Egypt combined religion, monarchy and the law; these aspects were still in play at Runnymede in 1215 when bishops and barons met with the king to write the Magna Carta. Gloves were used for ceremonial events such as these, as they are today.

Gloves became a symbol of power as well as a badge of office. Before long they were one of the most significant items of dress. A monarchs glove might be sent as a symbol of the delegation of power, and royal permission to hold a fair was demonstrated by the display of a large glove at the entrance.

A MONARCHS GLOVE

At the coronation of our current Queen, Elizabeth II, one highly embroidered glove was an essential element of the ceremony, as gloves have been since the start of the ceremony itself, when Edgar the Peaceful was crowned in Bath in AD 973. The Worshipful Company of Glovers provided the glove for Elizabeth II and it was made by Dents of Warminster. It is of a gauntlet style and much larger than the ones given to the Lord Chief Justice. Her Majestys glove was fit for a Queen. The similarity to the coronation glove of Queen Elizabeth I is striking and the only substantive difference over four hundred years is that the modern glove fits better.

Left: Doeskin gloves, c. 161035, dyed mid-brown, with wide integral gauntlets, thought to have belonged to King James I.

Right: Detail from one of these gloves.

British monarchs led busy lives and had uses for gloves far beyond just the ceremonial. In the sixteenth century, riding, hawking and all manner of social occasions required gloves, never mind occasionally going into battle. During Elizabeth Is reign gloves moved rapidly beyond the utilitarian and the symbolic: they remained hugely important as gifts and with the opportunity to embroider them with beautiful and high-value threads and precious stones, statements could be made at a wide range of price levels.

Gloves were so important that many gloves that were owned by monarchs have been preserved. Each king or queen would have had many pairs, often leaving pairs at the different palaces and houses they frequented, and keeping a store to use as gifts. In the early seventeenth century King James I owned many fine pairs of doeskin gloves. These were dyed mid-brown, with wide integral gauntlets applied with triangles of purple silk and over-embroidered in silver purl threads, couched silver thread and sequins with coiling blooms, interspersed with couched threads forming fruits and hearts. Three bands of purple silk edged in silver lace are sewn to the gauntlet sides, the elongated fingers are outlined in twisted silver braid, and the gloves are lined in brown silk and edged in pink flossed silk and gold thread fringing. Such gloves involved a huge amount of craftsmanship. Fine gloves of the period were also often made using kidskin.