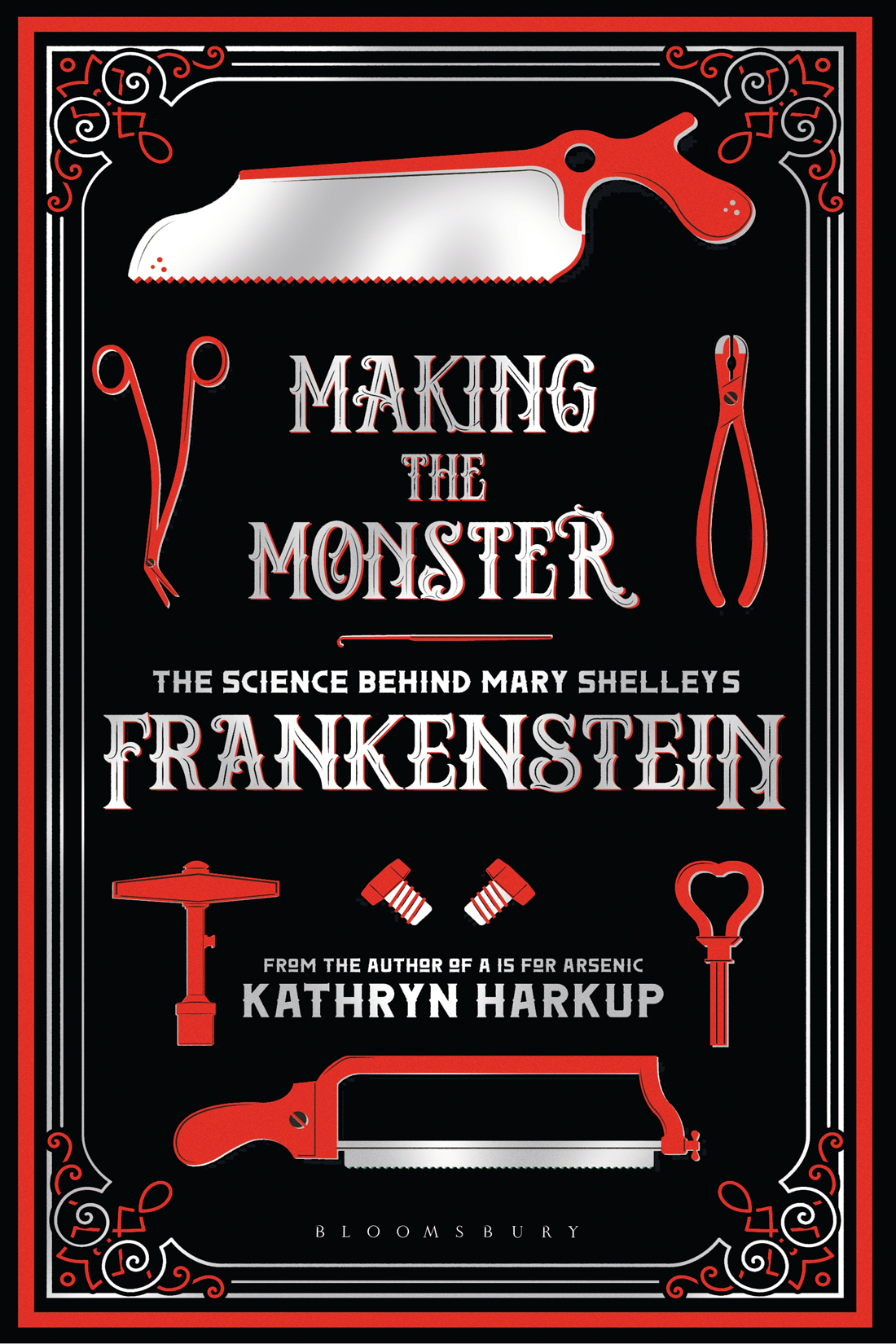

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p53: The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms Under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

Chilled by Tom Jackson

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

My European Family by Karin Bojs

4th Rock from the Sun by Nicky Jenner

Patient H69 by Vanessa Potter

Catching Breath by Kathryn Lougheed

PIG/PORK by Pa Spry-Marqus

Wonders Beyond Numbers by Johnny Ball

The Planet Factory by Elizabeth Tasker

Immune by Catherine Carver

Wonders Beyond Numbers by Johnny Ball

I, Mammal by Liam Drew

Reinventing the Wheel by Bronwen & Francis Percival

Contents

On 4 November 1818, a scientist stood in front of the corpse of an athletic, muscular man. Behind him his electrical equipment was primed and fizzing with energy. The scientist was ready to conduct a momentous scientific experiment.

The final preparations were made to the cadaver a few cuts and incisions to expose key nerves. No blood ran from the wounds. At that moment the thing on the table in front of the young scientist was just flesh and bone, from which all life had been extinguished. Then the corpse was carefully connected to the electrical equipment.

Immediately every muscle was thrown into powerful convulsions, as though the body was violently shuddering from cold. A few adjustments were made and the machine connected a second time. Now full, laborious breathing commenced. The belly distended, the chest rose and fell. With the final application of electricity the fingers of the right hand started to twitch as though playing the violin. Then, one finger extended and appeared to point.

The images conjured up by this account may seem familiar. Perhaps you have seen them on the silver screen when Boris Karloffs iconic creature twitched and stumbled into life. Or maybe you have read something like this in the pages of a novel written by the teenage Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. But the description above is not fiction. It happened. Two experimenters, Aldini and Ure, made the dead move using electrical devices.

Mary Shelleys debut novel Frankenstein created more than just a monster. It was the start of a new literary genre science fiction. But Mary Shelleys science fiction owes a lot to science fact. Written at a time of extraordinary scientific and social revolution, her novel captures the excitement and fear of new discoveries and the power of science.

But these philosophers, whose hands seem only made to dabble in dirt, and their eyes to pore over the microscope or the crucible, have indeed performed miracles.

Mary Shelley , Frankenstein

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (ne Godwin) was born on 30 August 1797 and died on 1 February 1851. The 53 years of her life were packed with scandal, controversy and heartache. It has been said that she embodies the English Romantic movement. She was survived by her son Percy Florence Shelley, named after his father, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary Shelley lived at a time of political, social and scientific revolution, all of which she drew upon to create her masterpiece, Frankenstein .

How did a teenager create a work of fiction that has enthralled, inspired and terrified for two centuries? Like the infamous monster of her creation, stitched together from an assortment of fragments, Marys novel took a collection of oddments from her own life and weaved them together to make a work much greater than the sum of its parts. Scenery from her travels, people she met and numerous influences from books she had read made it into the final work.

The novel, first published in 1818, was to dominate her literary legacy just as the monster dominated the life of his creator, Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein gave Mary fame, if not fortune, and was recognised early on as a classic of English literature. In 1831 it was included in a series of standard English novels and this second publication gave Mary the opportunity to revise and edit her work. It is this later edition that is more widely read, but this book will examine both editions.

Frankenstein is often cited as the first science-fiction novel, but there is much scientific fact to be found within its pages. This book looks at many of the influences on the novel and particularly the science behind the story. Marys characters were inventions although they were heavily based on real people but the science her characters studied was very real. Even the alchemists that fascinated the fictional Victor Frankenstein were real people. Marys science fact veered off into science fiction when Victor made his sensational discovery of the secret of life.

To understand how Mary pieced together her creation it is worth spending a little time looking at the political, social and scientific world that she grew up in as well as the people and experiences that made their way into the novel. The ideas and concepts explored in Frankenstein science, life, responsibility were at the forefront of philosophical and public debate in the century preceding the books publication. There were many other influences from Marys childhood that will be explored in subsequent chapters before we look at the scientific aspects of the novel and the character of Victor Frankenstein in detail.

The eighteenth century is known as the Age of Enlightenment. A time when prominent thinkers began to examine and question not only political theory, but also religious authority and how radical principles might be used as a means of social improvement. One method of social improvement was education, increasing the knowledge or Enlightenment of everyone, not just a privileged few. Immanuel Kant, a prominent German philosopher of the time, defined Enlightenment in 1784 as mankinds emancipation from self-imposed immaturity, and unwillingness to think freely for oneself.

The century preceding Marys birth was a time of political turmoil and political unrest was a feature of much of her early life. Over the course of the eighteenth century much of Europe moved away from a medieval system of government towards the modern system of statehood. The transformation was not simple or easy. Borders moved frequently, smaller estates were subsumed into larger nation states and wars were fought over land, and the control of that land. For example, when Mary was born and for the first 17 years of her life Britain was almost continuously at war with France.

Rulers sought to consolidate their power, many becoming the sole source of government over vast regions and peoples. Many rulers were influenced by the values of Enlightenment and sought to improve the lot of their subjects. Strange as it may seem to modern eyes, these individuals were welcomed by contemporary philosophes and became known as enlightened despots.