This book made available by the Internet Archive.

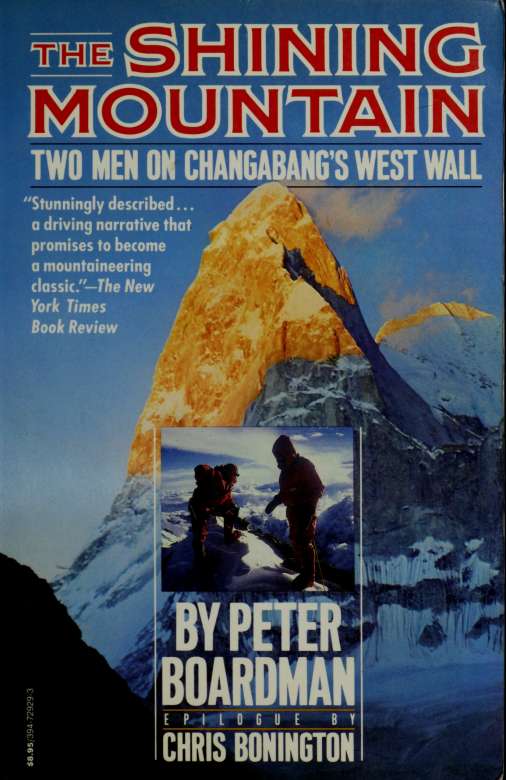

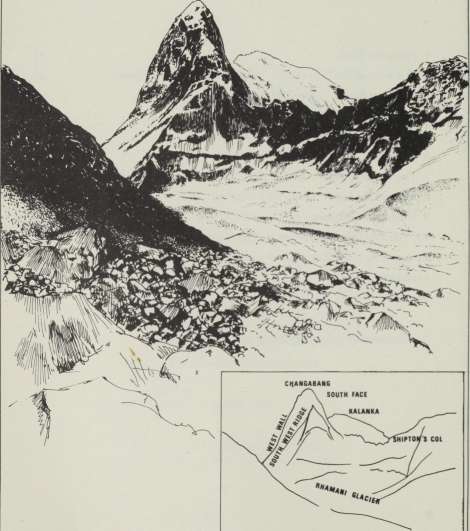

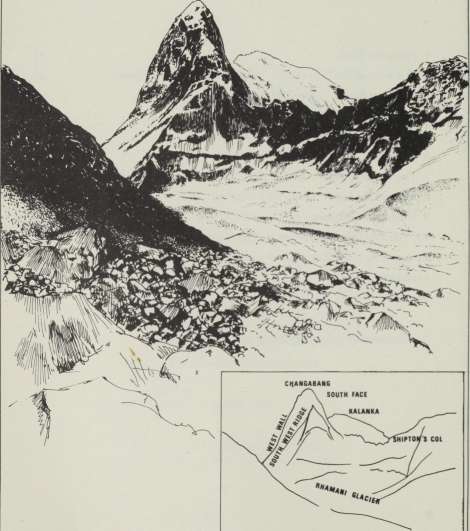

Changabang front the south-west

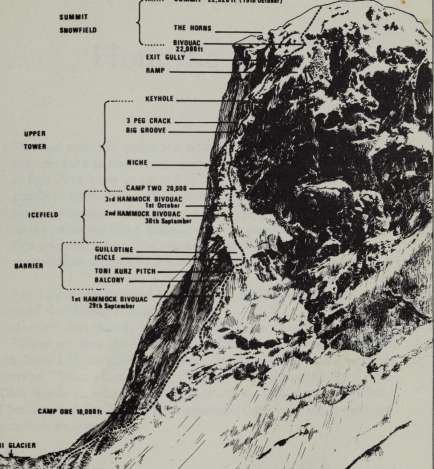

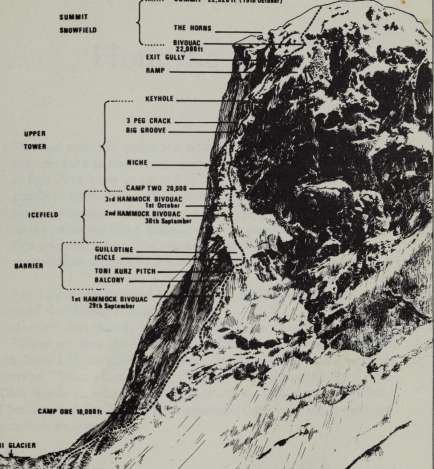

SUMMIT 22.620 ft (IStk Octtbtr)

SUMMIT SNOWFIELO

ICE SLOPE T J '.'/ "'--. / . , , J .

XM^''^mf

s//rr

y

v

\.

"**.^Ca ADVANCE CAMP 17.911ft

The route up the West Wall

CHAPTER ONE

From the West

"Sitting huddled beneath a down jacket, sheltering from thb sun, my back against a rock, I drank some liquid for the first time in four days. I was going to live. The photographs I took were purely a conditioned reflex; I would want one picture of this view, just as a reminder of the ordeal I had endured. The glacier, spread about before me like a white desert, was peopled by my imagination and over it hung the massive West Wall of Changabang, a great cinema screen which would never have figures on it."

Joe Tasker had survived Dunagiri and had returned to life to the west of the Shining Mountain.

Autumn days passed; meanwhile I was in the western world.

"Have you seen this letter?" asked Dennis Gray across the office of the British Mountaineering Council in Manchester, where we both worked. "What a fantastic effort," he added. I picked it up. It was from Dick Renshaw, who had just been on an expedition to the Garhwal Himalaya with Joe Tasker. The magnitude of their achievement jumped out from its few words:

Dear Dennis,

We climbed Dunagiri. It took us six days up the South-East Ridge. When we reached the summit, we ran out of food and fuel to melt snow into water. The descent took five days and we suffered. I got frostbite in some fingers and shall be flying home soon from Delhi. Joe's driving the van back.

Yours, Dick. P.S. Congratulations to Pete on climbing Everest.

I sat down, filled with envy. Dennis was already on the 'phone to the local press. "Incredible feat of endurance ...Just the two of them ... Tiny budget... 23,000-foot mountain ... Far more significant than the recent South-West Face of Everest climb." I had to strain to hear the words above the clattering typewriters and rhythmic pumping of the duplicating machine. Beyond the plate glass windows, the red brick of the office block, the unkempt, lumpy car park, and the Home for the Destitute, I could glimpse the blue of the sky.

I stared dumbly at the trays of letters in front of me access problems, committee meetings, equipment enquiries. Amongst them were invitations to receptions and dinners and requests to give lectures about the Everest climb all demands to accelerate the headlong pace of my life. Their number diluted the quality of my work. 'Everest is a bloody bore/ screamed a voice inside my head. The previous evening I had given a slide show about Everest. It was as if I was standing aside and listening to myself. As time distances you from a climb, it seems you are talking about someone else. All the usual questions had rolled out at the end: What does it feel like on top? What do you have to eat? How do you go to the toilet when you're up there? Is it more difficult coming down? How long did it take you? Don't you think you've done it all now you've been to the top of Everest? What marvellous courage you must have!

Courage. Endurance. Those words drifted across the office and mocked my bitter mood of discontent. Meaningless. Courage is doing only what you are scared of doing. The blatant drama of mountaineering blinds the judgement of these people who are so loud in praise. Life has many cruel subtleties that require far more courage to deal with than the obvious dangers of climbing. Endurance. But it takes more endurance to work in a city than it does to climb a high mountain. It takes more endurance to crush the hopes and ambitions that were in your childhood dreams and to submit to a daily routine of work that fits into a tiny cog in the wheel of western civilisation. 'Really great mountaineers.' But what are mountaineers? Professional heroes of the west? Escapist parasites who play at adventures? Obsessive dropouts who do something different? Malcontents and egomaniacs who have not the discipline to conform?

"Will you answer this, Pete?"

"Oh yes, sorry."

Rita, one of the secretaries, was holding a 'phone out towards me. "Someone's ropes snapped, and the manufacturer says it isn't his fault."

"O.K. I'll deal with it." In the city, as on the mountain, there has to be a breaking point.

I had nearly died on Everest that September. With Sherpa Pertemba, I had been the last person to see Mick Burke, who had disappeared in the storm that swept over us during our descent from the summit. We had lost him on the summit ridge and it had been my decision to descend without him. But I had returned to the world isolated by a decision and experience I could not share. My internal resources had grown. At first, during the desperate struggle of the descent, I had a surge of panic. We nearly lost our way twice, and were constantly swept by avalanches in the blizzard, but then I felt myself go hard inside, go strong. My muscles and my will tightened like iron. I was indestructible and utterly alone. The simplicity of that feeling did not last beyond our arrival at Camp Six and the thirty-six hours of storm that followed. But I was to remember it in the months that followed.

Now back in Manchester, I was tired and depressed. My life had become dominated by one event. On Everest, the summit day had been presented to me by a large systematised expedition of over a hundred people. During the rest of the time on the mountain, I had been just part of the vertically integrated crowd control, waiting for the leader's call to slot me into my next allocated position. And yet, when I returned to Britain, as far as the general public were concerned I was one of the four heroes of the expedition, the surviving summiters. The applause rang hollow in my loneliness and the pressures of instant fame, although short-lived, made me ill. I yearned hopelessly for privacy so that I could digest the Everest experience. I longed for time to allow the thoughts which came to me in the early morning to take on form and meaning again.

I was now public property and, after eleven weeks away from the office, was left under no doubt that I had been allowed on my last expedition for a couple of years. I had sixteen committees to serve. Yet I felt in need of some new, great plansome new project. I wanted to see how far I could push myself and find out what limits I could reach on a mountain. At the age of twenty-four there seemed so many mountain areas and adventures just within my grasp.