Edited: Rebecca Spence and Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel

embodied in reviews and articles.

P.O. Box 52287

Names: Fishbaum, Silvia, author. | Coddington, Andrea, 1975- author.

Title: Dirty Jewess : a womans courageous journey to religious and political freedom /

by Silvia Fishbaum with Andrea Coddington.

Description: First edition. | Brooklyn, NY : Urim Publications, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017056880 | ISBN 9789655242775 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Fishbaum, Silvia. | Jewish womenCzech RepublicBiography. |

Czech AmericansBiography.

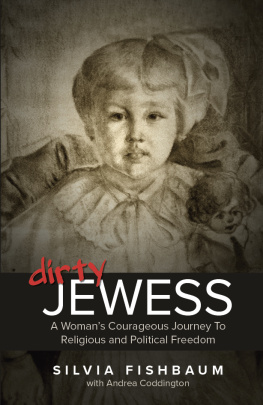

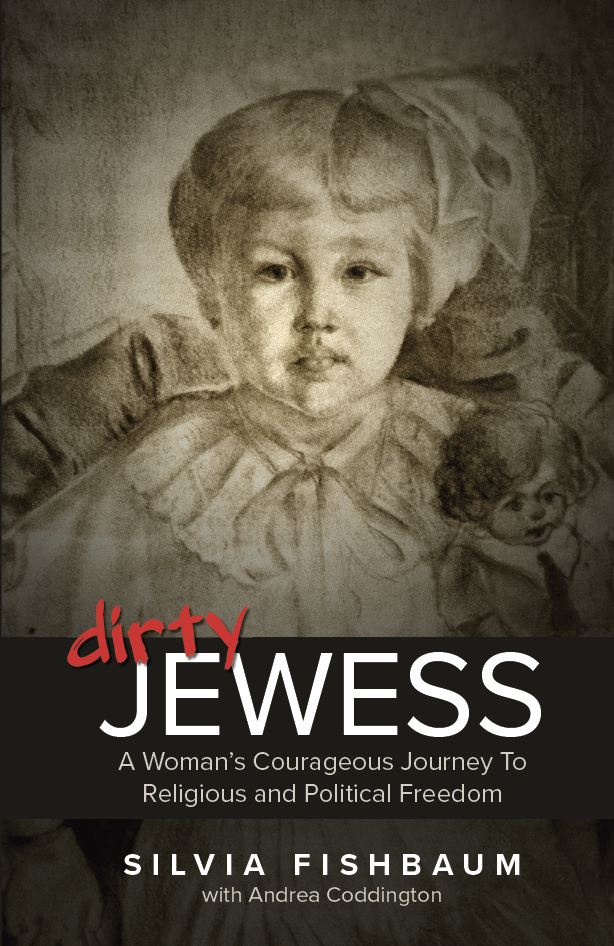

The Girl with her Doll.

Original charcoal drawing, 1933, by Lajos Feld.

( Photo credit: David Feldman )

Contents

Acknowledgments

It was Andrea Coddington who first brought my story titled Zidovka (Dirty Jewess) to life. It was published in Slovakia in 2010 by Ikar and quickly became a platinum bestseller, selling more than 25 thousand copies in its first year with long waiting lists in every single library around the country.

I have enormous gratitude for her encouragement and support in nurturing this book from its inception. Andrea has never been exposed to Judaism before and she took to it like fish to water. Together we threaded those deep, dark corridors down memory lane. We laughed and cried along this great adventure.

This book would not have been possible without the desire to keep the memory of my parents, both Holocaust survivors, alive.

I also wish to honor the memory of my childhood art teacher, Ludovit Feld, for he became the inspiration to fulfil my late husbands wish.

My intention was to have the book in English to let my children, family and friends know what it was like growing up in the post Holocaust communist Czechoslovakia, for those who stayed behind the iron curtain the plight of the second generation. I would like to assure everyone that, yes, your dreams do come true and one should never give up.

Never did I envision such a success of my memoir, as I hoped to stay somehow anonymous. Therefore most of the names in the book are changed, although all the locations are authentic.

I would like to thank Gabriel Levicky for his enthusiasm in helping me create the first English draft.

Likewise I am genuinely indebted to Stacy La Rosa for her invaluable passion to find my voice in English.

A big hearty thanks go to Rebecca Spence for her efforts and suggestions in shaping the first copy of the manuscript.

A boisterous and thunderous thanks goes to Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel. Her brilliant wisdom, comments, and savvy feedback helped bring the book to its final version.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my entire family, relatives, friends and peers who surrounded and supported me. I am truly lucky to be encircled by all of you.

Last, but not least I would like to acknowledge my gratefulness to Pearl Friedman, editor at Urim Publications, for her input and beautiful, encouraging words.

In memory of our loved ones

and all those who live in our hearts for eternity.

I, Sophia Manisevicova, would like to thank you

for holding this book in your hands.

And the next time we meet, on the very last page,

I want you to know that my real name

is Silvia Fishbaum, and this is the story of my life.

Chapter One

The Only Jews in Our Village

Porubka, Czechoslovakia Fall, 1961

M y parents had eagerly expected a son who would perpetuate our familys name and traditions, and it was equally important to them to have a son who would recite the Kaddish memorial prayer after they were gone. According to Halacha , or Jewish law, only males are required to perform this ritual.

However, my parents had three daughters: the oldest is the beautiful Melanie, the middle one is Hanka, and I am Sophia, who was known as the little rabble-rouser.

I am darker-complexioned and a bit more impulsive than my two sisters. Because of my temper and coloring, people joked that I must have fallen out of a Gypsy wagon on its way down the dirt road in our rural village of Porubka. My parents, Simone and Yaakov, must have found me and done a good deed, a mitzvah , by taking me in as their own. Since I was their last girl, my parents would have the barber cut my hair so that at least I would resemble a boy.

I had no clue what it meant to be Jewish.

One Friday, when I was six years old, my mother seemed somewhat different. She was a bit more at ease than her usual nervous self. It was no wonder, as her soul had been filled with pain and sorrow for so long, and her sense of serenity had been snatched away from her many years before. But on that particular day, she appeared less tense, and even smiled a little. Although she was a beautiful woman, you could see traces of horror and suffering in her eyes. She could never really laugh, and she seemed hesitant to fully embrace life. Constantly on guard, in silent tension, she went through her days with strength, dignity and poise.

Shabbos is a delicate gift from God, Mother loved to say, as if giving us a peek behind the veil of mystery of Shabbat, or Shabbos. We honor Shabbos and Shabbos honors us back.

She knew quite well that we were absorbing every word, listening as though we could never get enough. But while we were enraptured by her tales, we also knew how much was left unsaid.

I always cherished Fridays. From the wee hours of the morning, my mother would be even busier than usual in the kitchen, so that come evening, my family could sit together around the Shabbat table, relaxing, watching and enjoying the sunset. My father would play board games, cards, and dominoes with my two sisters and me, or read us story books and tell tales about our small country of Israel. While Mother was busy at the stove, she would nod approvingly at the whole scene, receiving pleasure or schepping nachas, as she would say. The kitchen was her kingdom, always clean and tidy, with spice racks neatly placed beside fresh loaves of homemade bread, which she enhanced with her own handmade embroidered covers. The aroma penetrated every nook and cranny of our peasant house.

Honoring Shabbos has always kept Judaism alive, my father would say. We hold on to it, we lean on it no matter where in the world we are, whether drowning in our sorrows, or filled with gratitude. And we, as a people, are there for others as well.