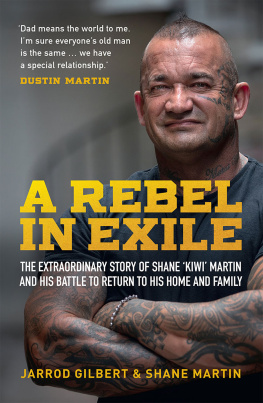

This book is dedicated to Kiwis family.

Wed also like to thank Ben Elley, who was instrumental in putting this book together.

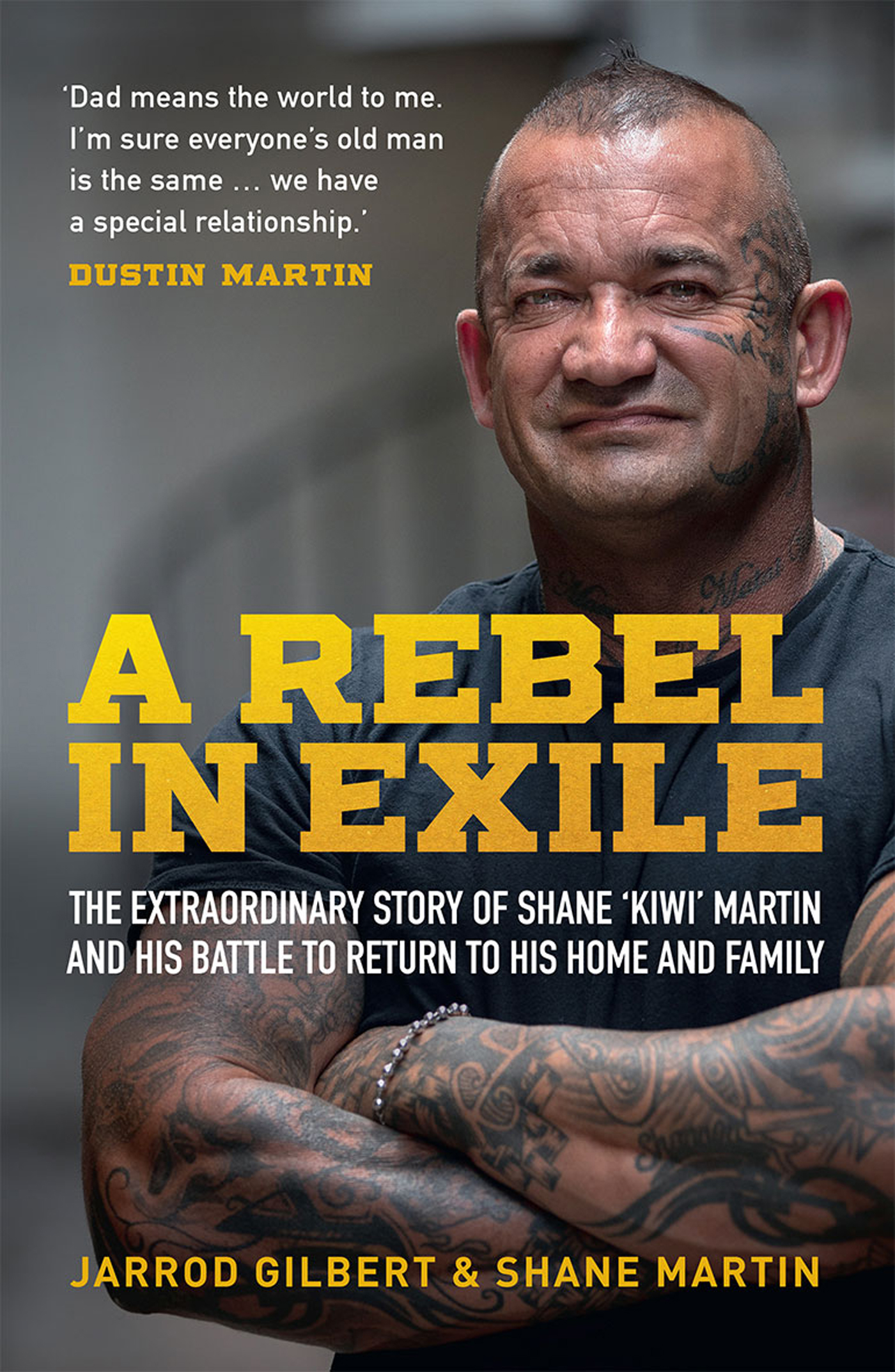

Dr Jarrod Gilbert is a New Zealand sociologist at the University of Canterbury and the lead researcher at Independent Research Solutions. He is the author of Patched: The History of Gangs in New Zealand, an award winning and bestselling book, and the co-editor of Criminal Justice: a New Zealand Introduction. He advises a number of New Zealand government agencies on policy matters and sits on the Academic Advisory Panel to the Department of Corrections, the advisory group of the cross sector High Impact and Innovation Team and he is a member of the Justice Advisory Group currently investigating changes to the criminal justice system in New Zealand.

CONTENTS

How will I know who you are? I asked.

Youll know me when you see me, came the reply. So I headed off to a bar called the Royal Oak in Double Bay, Sydney to meet a guy I only knew as Kiwi.

I had been sent to Australia by UK documentary maker and mate of mine Ross Kemp to investigate the possibility of making a program on Aussie bikies. In my capacity as a sociologist and researcher, Id done a lot of work on gangs in New Zealand, and some of the outlaw clubs had chapters in both countries, so in August 2014 I jumped across the ditch to see what I could do.

I was about a week and half in when I arranged to meet Kiwi in Sydney. By that time my liver had received a pretty good working over in Adelaide by a club called the Descendants, but I was looking forward to meeting a guy who was a well-known member of the Rebels, Australias largest outlaw motorcycle club.

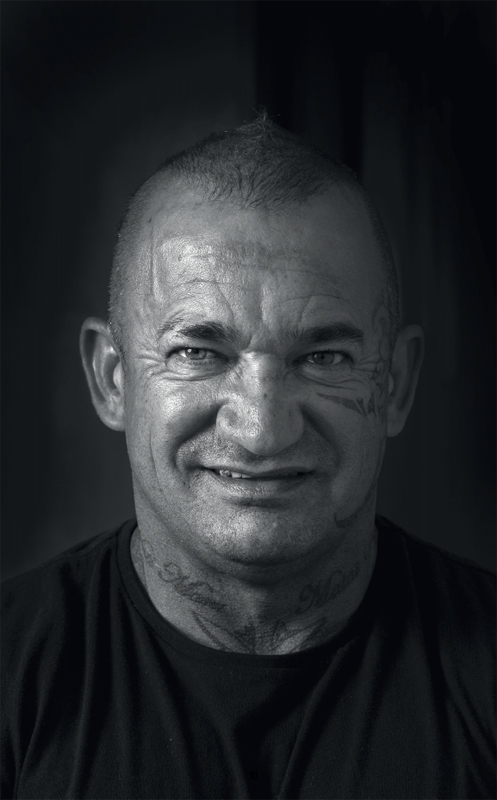

The bar, a fairly up-market joint, was pretty full, but Kiwi was obvious. He had been to see his son a rising superstar apparently play footy for Richmond (his team had won). He was dressed in an expensive-looking white shirt and smart dark pants, so it wasnt his clothes that made him stand out. It was the size of the man; he was a big bloke. Wide but not tall. Built, as they say, like a bull. That and the tattoos. His hands, neck and face were all inked. He was also Mori, and that made sense of the name Kiwi.

That will be my man, I thought.

What struck me was his accent. Nice to meet you, mate, he said, extending a hand. It was undeniably Australian.

He had a few lads with him and I bought a round of drinks. That hospitality was returned in spades and the next thing I knew I had a cracking good hangover and an extremely good contact in a guy whose real name, I learned, was Shane Martin.

A few days later I headed to Brisbane to meet the Hells Angels. I also went to a court case challenging the anti-gang legislation that had been put into place by a polarising Queensland premier named Campbell Newman.

At the end of the trip, I returned home to Christchurch, New Zealand and to my office at the University of Canterbury, and I began a long email to Ross Kemp. It ended like this: Mate, there is a documentary here alright, but not the one youre expecting. The focus shouldnt be on the bikers but on the laws targeting them.

When we made the documentary, I pressed the whole crew to do something that was counterintuitive and that was to back the bikies against the state. I thought the laws were an affront to justice and, usually after too many wines in the evenings of filming, I would assure the director by loudly and confidently proclaiming that we would find ourselves on the right side of history.

Ill talk more about this as we proceed, but at that time I was convinced the laws would be overturned. I was wrong.

In fact, legislative measures targeting gangs and others got more extreme. When Shane Martin was targeted on immigration matters, I felt compelled to look at things again, not least because the police had used still shots from the documentary as evidence against him. Could I have somehow contributed to his predicament? It was an uncomfortable thought.

I wanted to find out what on earth was going on so I sat down with Kiwi and tried to figure it out. Kiwi told me stories that interested me, saddened me, confused me, and made me angry. Wait, wait, wait, I said to him, I cant get my head around all this. Take me back to the start.

He told me he had grown up in Huntly, New Zealand. And thats where this story begins.

Huntly is a shithole, if Im honest. I dont remember when I first thought of leaving for Australia, but it was a great decision.

Its a little town on the highway between Auckland and Hamilton, with State Highway 1 running through the middle of it next to the train tracks. A flash of some shops on the drive through is the most people see of it, and thats the most they want to see of it.

We lived on the south side of the town in a fairly basic home across the river from the main street. Huntly is inland from the sea, but the Waikato River is big and wide and runs through the centre of town. The coalmine to the west rumbled and blasted all day, and the newly opened power station to the north burned coal day and night to keep the lights on in Auckland.

There were four of us kids, all boys. I was the oldest. My mum was Mori and a heavy drinker. My dad, another heavy drinker, was Pkeh. We moved from the east coast to Huntly when I was a toddler because my dad found work at the coalmine, but we would go back to the Coromandel Peninsula to see the family on Mums side, often to go camping. Wed fish a fair bit and collect those little freshwater crayfish.

But I dont remember much about my childhood. My cousin told me once that we had it really tough, but it just seemed normal to me. You only know what you know.

Money wasnt the problem. Dad was a provider. He worked big hours driving a dozer at the coalmine, the same as most of my friends dads. He went to work before the sun came up and when he pulled into the driveway the sun had already set in the winter, anyway. After pulling his dusty boots off hed sink into his chair without really looking at us. A day at the mine made him grumpy, so we kept out of the way.

When Dad got home he expected dinner. If Mum hadnt made it, they would row. Even more so when Mum had been drinking, and more again if he had too. If the neighbours could hear them yelling, they never said anything. All I remember about that house is the fighting, and us kids were always getting hidings. Proper hidings.

But my parents left us alone most of the time. Dad came home late and Mum would go out and party with her friends. Kids roamed the streets barefoot and unsupervised in 1970s New Zealand, but my brothers and I stayed out later than most.

Some nights Id cook for my brothers. All I knew how to make was spuds and sausages, so thats what we had most times. Other times wed take money out of the kitchen drawer and walk down to the fish and chip shop. If Mum was passed out on the rug wed eat in the backyard.

It wasnt all bad. Anyone who grew up in the seventies will remember what happened when BMX bikes came about. Every kid wanted one and I was no different. I was on and on at my old man, saying to him, All of my mates have bikes. Can I please have one?

I was being a bit of a sook, but I so badly wanted a BMX.

One day the old man came home and told me to go get the groceries out of the car. I dragged my feet a bit. But when I got there I saw there was a bike in the back and I couldnt believe it. I grabbed it out and rode down to show all my mates. I barely got off that bike as a kid.