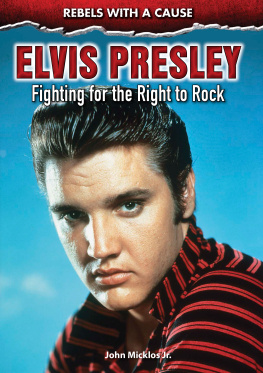

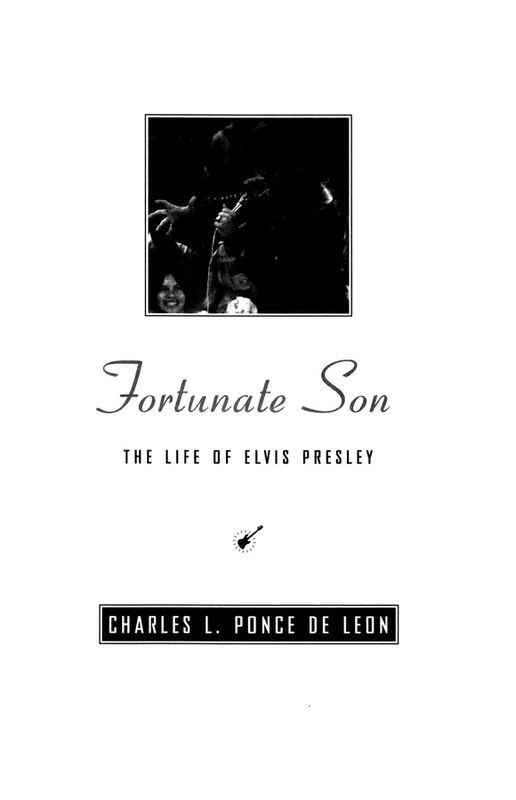

IT BEGAN AS an unexceptional incident, the sort of thing that filled police blotters in the crime-ridden 1970s but otherwise attracted little notice. Shortly after midnight on June 24, 1977, two young toughs began roughing up the lone attendant at an all-night gas station in Madison, Wisconsin. Before they could get very far, a limousine pulled up. Its back passenger door swung open, and a large man in a tracksuit and oversize sunglasses jumped out and strode toward them. He assumed a karate pose. Bewildered, the bullies strained to get a better look at the interloper. What they saw made them stop in their tracks. It was Elvis Presley, the singer and movie star. Having just arrived in Madison for a concert that evening, he was on his way to his hotel when he saw the altercation and resolved to help the attendant.

The shock of seeing Elvis completely changed the situation. The young toughs backed away from their victim, who was just as stunned as they were when he recognized his rescuer. Police officers accompanying Presleys limousine then intervened. But Elvis hung around for some time afterward, talking to the officers as well as the victim and his assailants. He attendant, especially with the police so close at hand?

This minor incident, one of countless Elvis anecdotes that constitute the Presley lore, speaks volumes about the man and the peculiar status he came to acquire during his relatively short yet illustrious career as a performer, recording artist, and movie actor. As the reaction of the men at the gas station demonstrated, Presley had already become something of a recluse by the mid-1970seven while regularly appearing before thousands of fans on concert tours that sent him to cities throughout the country. Since the early 1960s he had inhabited a cloistered world outside the public eye, but in recent years his interest in protecting his privacy had become stronger than ever. Stung by press criticism of his poor performances and portly, debauched appearance, Presley rarely went out in public, except late at night, when he knew few people would be around. Even when he was alive, an Elvis sighting was an exceptional occurrence. It was as if he had emerged from a parallel universe and the rarity of such an event demanded special commemoration. He was already an icon, a living legend.

Elvis was aware of this, and it was recognition of his iconic power that led him to stop the limo and go to the attendants aid. Though Presley was in many ways an unpretentious man, he was also convinced that his success was evidence of some divine calling and that he was obliged to use his star power for good. This belief inspired his perception of himself as a performer and encouraged him to chart a career path that remained remarkably consistent in its fixation on mainstream success and conventional show-business values. Over time, it also led him to see his celebrity in more grandiose terms, as a pulpit from which he could reach the public and heal the divisions created by the fractious social and political conflicts of the 1960s. Elvis thought of himself as a good guy, like the heroes in the comic books and B movies he loved as a boy. And by the early 1970s this understanding of himself had made him sympathetic to political conservatism and a self-righteous advocate of law andorder. It was no coincidence that when he jumped out of the limo in Madison, he was carrying his badge from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, or that in the car was an assortment of firearms that he and his bodyguards took with them nearly everywhere. Like the FBI or the vigilante crime fighters who dominated the eras popular culture, he was protecting the weak from the forces of anarchy that seemed to be engulfing the nation.

As Elvis saw it, he was a fortunate son, a child of the Depression-ravaged South who had become successful beyond his wildest dreams. Grateful for his success, he was determined to give something back to the nation that had made it possible. Doing so would not only honor America, the land of opportunity; it would also honor his parents. Humble, working-class Southerners, they had struggled to provide him with a decent life. They had also raised him to be respectable: a wholesome, law-abiding, God-fearing young man. Elvis revered these values. He regarded himself as someone who lived by them, and he was certain they had been instrumental to his success, enabling him to gain the affection and loyalty of fans from a variety of backgrounds. Making people happy with his music, setting a good example for the public, serving the cause of law and order as best he couldthis was Elviss way of paying homage to his upbringing and the respectable working-class culture from which he sprang. It was also a way for him to reconnect with this culture and conceive of himself as its apotheosis, the poor boy from Mississippi who had achieved the American Dream yet remained faithful to his small-town roots.

By the summer of 1977, however, the real Elvis bore little resemblance to this image, and Presley was increasingly troubled by the disjunction between the two. After twenty years as a celebrity, subjected to the pressures of fame and with virtually anything he desired at his fingertips, he had become a self-indulgent libertine, a chronic womanizer, and a man plagued by doubts about the loyalty of his closest friends and associates. Convinced he was a target of bad guys, he was often armed to the teeth and prone to carelessly firing his weapons, a habit that had already gotten him into minor scrapes and seemed destinedto result in a serious accident. He was a drug addict, dangerously dependent on several potent prescription medications, despite his professed hatred for the drug culture and his identification with the police and organizations engaged in the war on drugs. And he was suffering from depression, a condition exacerbated by his abuse of drugs that heightened his paranoia and eccentric behavior.

Worst of all, these details, which had been published in bits and pieces in the tabloid press, were about to be splashed across the headlines. Three of Elviss former bodyguards had just finished a tell-all expose, the first to appear from within Presleys camp, and its impending publication greatly concerned Elvis. He feared that the book would destroy his reputation and, as fans came to learn the truth about him, force him to confront the gulf that had developed between the reality of his life and his revered self-image.

Is it any wonder, then, that Presley jumped out of his limo and rushed to the filling-station attendants aid? Here was a perfect opportunity to act like the man he liked to think he was, to shore up his faltering self-image, and to remind the public that no matter what they might hear about him in the near future, he was admirable, a good guy.

Unfortunately, less than two months after his escapade in Madison, Elvis Presley was dead, and the unflattering information contained in the dreaded bodyguard book became common knowledge. Thanks in part to the publicity sparked by his death, the book became a best-seller,

But these revelations didnt destroy Presleys image so much as transform it. While some fans refused to believe the sordid and at times exaggerated claims contained in the book and in subsequent exposs, others found ways of accepting them. In due course they were incorporated into a new understanding

Elviss story, from this perspective, is a tragedy, a story familiar in its essentials to many other accounts of celebrities lives. At its core is the belief that material success breeds unhappiness and corruption, and that the central drama of Presleys life was an ultimately unsuccessful effort to prevent this from occurringto ward off the forces that could turn the American Dream into a nightmare. Ironically, Presleys image while he was living emphasized his success at this endeavor. His fans and the wider public were encouraged to believe that despite his fame and riches, he was still the same wholesome, law-abiding, God-fearing man who had risen to stardom so suddenly in the mid-1950s. His lapses were attributed to the difficulties involved in remaining committed to ones values amid the temptations and snares of a secular consumer culturesomething large numbers of Americans could readily appreciate.