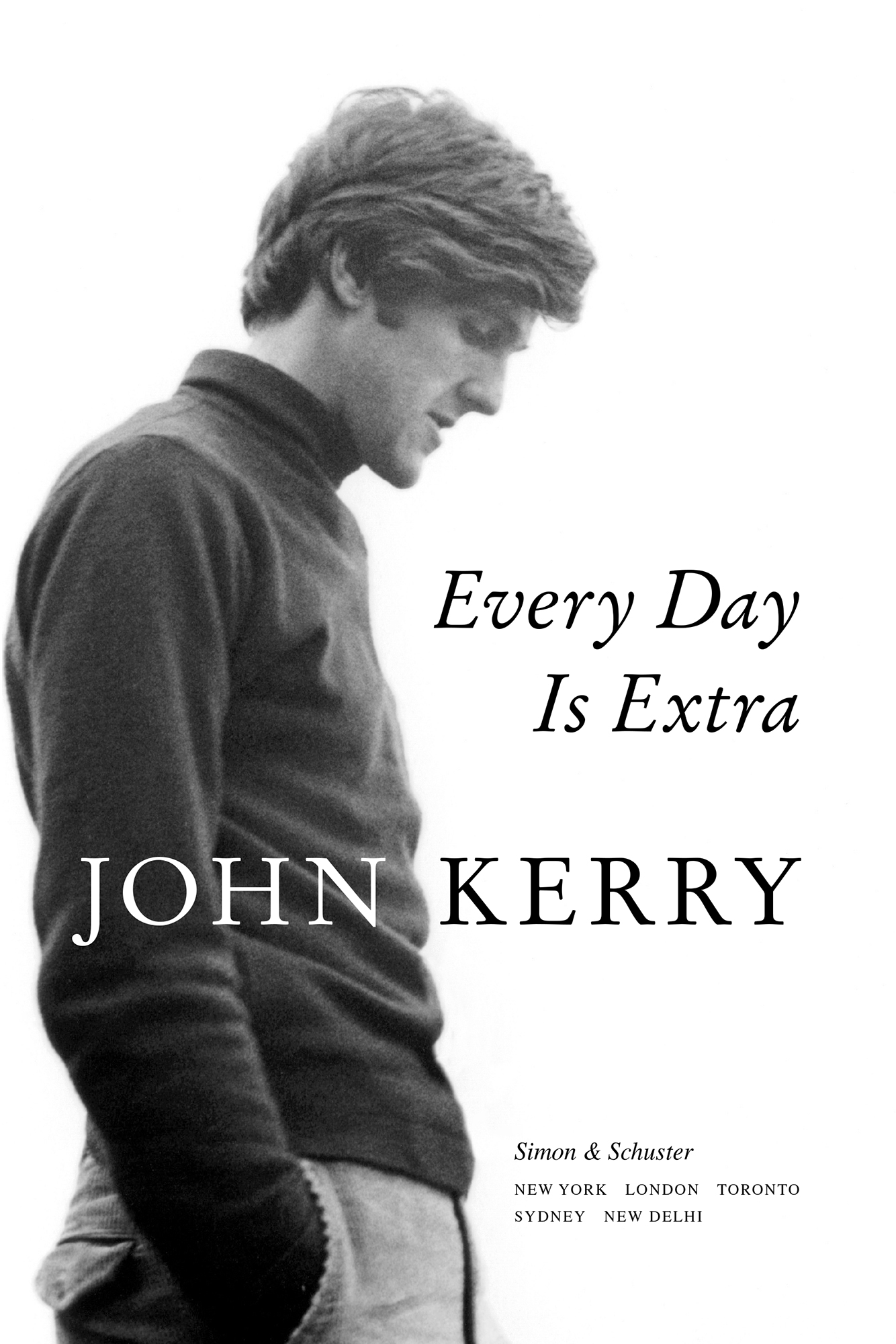

A LSO BY J OHN K ERRY

This Moment on Earth: Todays New Environmentalists and Their Vision for the Future (with Teresa Heinz Kerry)

A Call to Service: My Vision for a Better America

The New War: The Web of Crime That Threatens Americas Security

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2018 by John Kerry

Lyrics from The Times They Are A-Changin 1963, 1964 by Warner Bros. Inc.; renewed 1991, 1992 by Special Rider Music. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

The opinions and characterizations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent positions of the United States Government.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition September 2018

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Paul Dippolito

Jacket design by Jackie Seow

Front jacket photograph George Butler/Contact Press Images

Back jacket photograph 2018 by Kelly Campbell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-5011-7895-5

ISBN 978-1-5011-7896-2 (ebook)

To my grandchildrenAlexander, Allegra, Astrid, Isabelle, Jack, Livia and Sloanto their parents, to my wife, Teresa, and to the future

Authors Note

Every Day Is Extra is not just a statement of fact; its an attitude about life. It is an expression that summarizes how a bunch of the guys I served with in Vietnam felt about coming home alive. It is the recognition of a gift and a mystery. It is a philosophy lived by people who could have died on any given day but didnt when far too many good men did. It is an expression of gratitude for survival where others did not make it. It is a pledge accepting responsibility to live a life of purpose. And it is the recognition that those of us who survived when so many others didnt had better live our extra days in ways that keep faith with the memory of brothers whose days were cut tragically short. Finally, every day is extra means living with the liberating truth of knowing there are worse things than losing an argument or even an electionthe worst thing of all would be to waste the gift of an extra day by sitting on the sidelines indifferent to a problem.

This book is the story of my journey trying to keep faith with the gift of my extra days.

Theres a battle outside and it is ragin

Itll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls

For the times they are a-changin

Bob Dylan, The Times They Are A-Changin

CHAPTER 1

Childhood

W ONDERFUL, MY FATHER said in a soft, hoarse but somehow satisfied whisper, his eyes closed, savoring a bite of the Swiss chocolate he and I both loved since wedecades apartwere young boys in Swiss boarding schools under very different circumstances, young boys who found that rich and sinful indulgence helped fill a void.

It was the last mouthful of chocolate Pa would ever taste.

For nine years, the cancer had been a constant aggressor, but now, in late July 2000, after doctors promised him he would die of something else and advised a watch and wait response to his prostate cancer, it had relentlessly, cruelly found its way into his bones. The pain was agonizing. All we could do was liberally pump palliative morphine into his body to bring some measure of comfortor the next best thing: numbness.

My brother, Cameron, and my sisters, Peggy and Diana, and I were wandering through our childhoods as our father was slipping away, high in a tower of Massachusetts General Hospital, facing the Charles River and the playing fields of the park below. It was a warm, blue-sky July day. I could see a light breeze rippling the trees, while small sailboats dotted the Charles River basin in front of MIT. There was a part of me that yearned to be outdoors, feeling the summer warmth, far away from the reality that my father was about to die. But of course, reality has its harsh way of dragging you back to earth. Coincidentally, just days before, President Clinton had landed his helicopter in the fields below us during a visit to Boston. I had watched from the twenty-first floor while the world of the living, which had no inkling of the personal drama playing out in our lives, went on below. I was one of three finalists under consideration to be Al Gores running mate. It hit me that my father would never know the outcome of that decision. It was strange to juxtapose what I thought was important with the intimacy and finality of our world in that room.

Pa slipped deeper and deeper into sleep. His breathing became heavier and labored. Now we were just waitingmy sisters, brother and I sitting vigil at his bedside, the day after his eighty-fifth birthday. His breaths grew increasingly shallow. While we were cloistered, quietly and somberly, at Massachusetts General Hospital, our eighty-seven-year-old mother, his wife of more than sixty years, was resting at home, unable to wait with us the long hours for the inevitable. She had said her goodbye a day earliera painful bedside farewell in which her last words to him were Ill see you tomorrow. All of us in the room knew she wouldnt, and the tears in her eyes told us she knew it too. I wondered how you say goodbye like that to someone youve lived with for more than six decades, and I felt enormous pain for my mother, who was clearly overwhelmed by the moment.

I know I was lucky to have parents who lived as long as mine did, and grateful too for all of us to be able to be present to say our goodbyes, but Ive learned over time that no matter how old one is, no matter how much longevity there is to celebrate, when a parent dies, we are all of us, no matter what age, still children. Mothers and fathers fall into different categories altogether. Age and illness reverse the role of caretaker. And so it was with us. It fell to the four of usRichard and Rosemarys adult childrento helplessly wait for our father to die. At one point, we asked one another: Were we really certain he wanted to go? Did he want us to do something, anythingtake extra and more extreme steps, however futile they might beto give him a few more days? Was he really ready to take his leave?

Suddenly, so uncertain were we about Pas wishes, we went to considerable lengths to wake him to ask what he wanted. Pa, is there anything we can do? What do you want? His eyes grew wide and clear. He abruptly sat up in bed and forcefully announced, I want to die. Those were the last words Pa ever spoke. He lay back on the pillow, closed his eyes once more, and with all of us surrounding him, holding his hands, touching his arms, we watched him slip away.

I suppose for us children trying hard to divine our fathers last wish, the certainty of that announcement lifted a burden. It was a relief, a comfort, but it was jarring nonetheless.

Now he was gone. Even after my last-ditch efforts to pull out of him some answers, not just about lifes mysteries but about the mysteries of his life, I realized the brief accounts that he had given left me full of more questions than Pa was ever ableor willingto answer, not just so late in the day but also throughout his life. Some of his reticence to share more, I chalk up to the stoicism of those of the Greatest Generation. Even by that measure, however, Pa or Pop or Popsicle, as I sometimes teasingly called him, was still a complicated and perplexing man. What I hadnt fully realized as I was growing up was any of the reasons for his emotional reserve.

Next page