Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Casey N. Cep

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cep, Casey N., author.

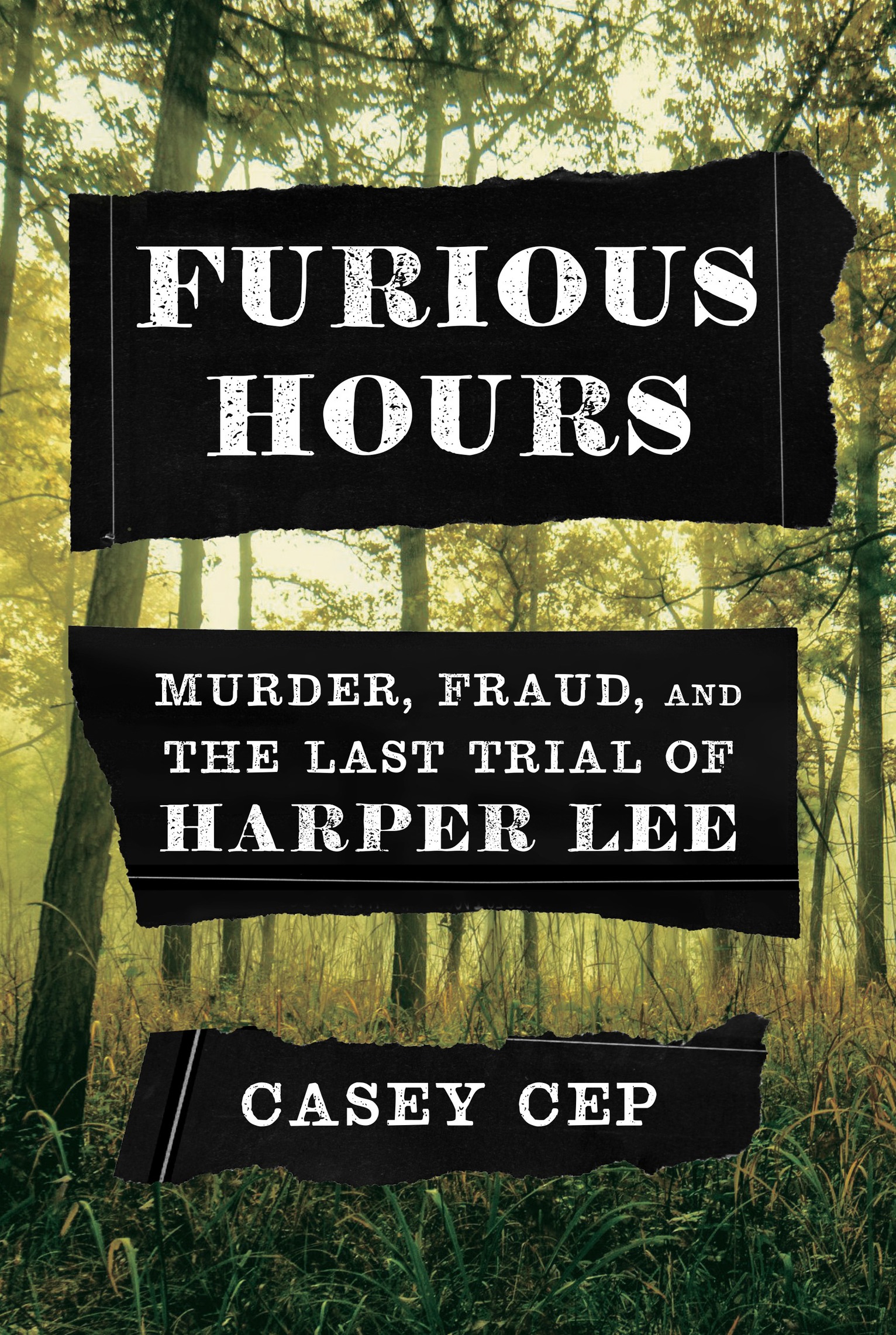

Title: Furious hours : murder, fraud, and the last trial of Harper Lee / Casey Cep.

Description: First Edition. | New York : Knopf, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018043337 | ISBN 9781101947869 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101947876 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Serial murdersAlabama. | MurderInvestigationAlabama. | Trials (Murder)Alabama. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | TRUE CRIME / Murder / Serial Killers. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / South (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV).

Classification: LCC HV6533.A2 C47 2019 | DDC 364.152/32092dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018043337

Ebook ISBN9781101947876

Cover photograph by BJ Ray / Shutterstock; (torn newspaper) by StillFx / Getty Images

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

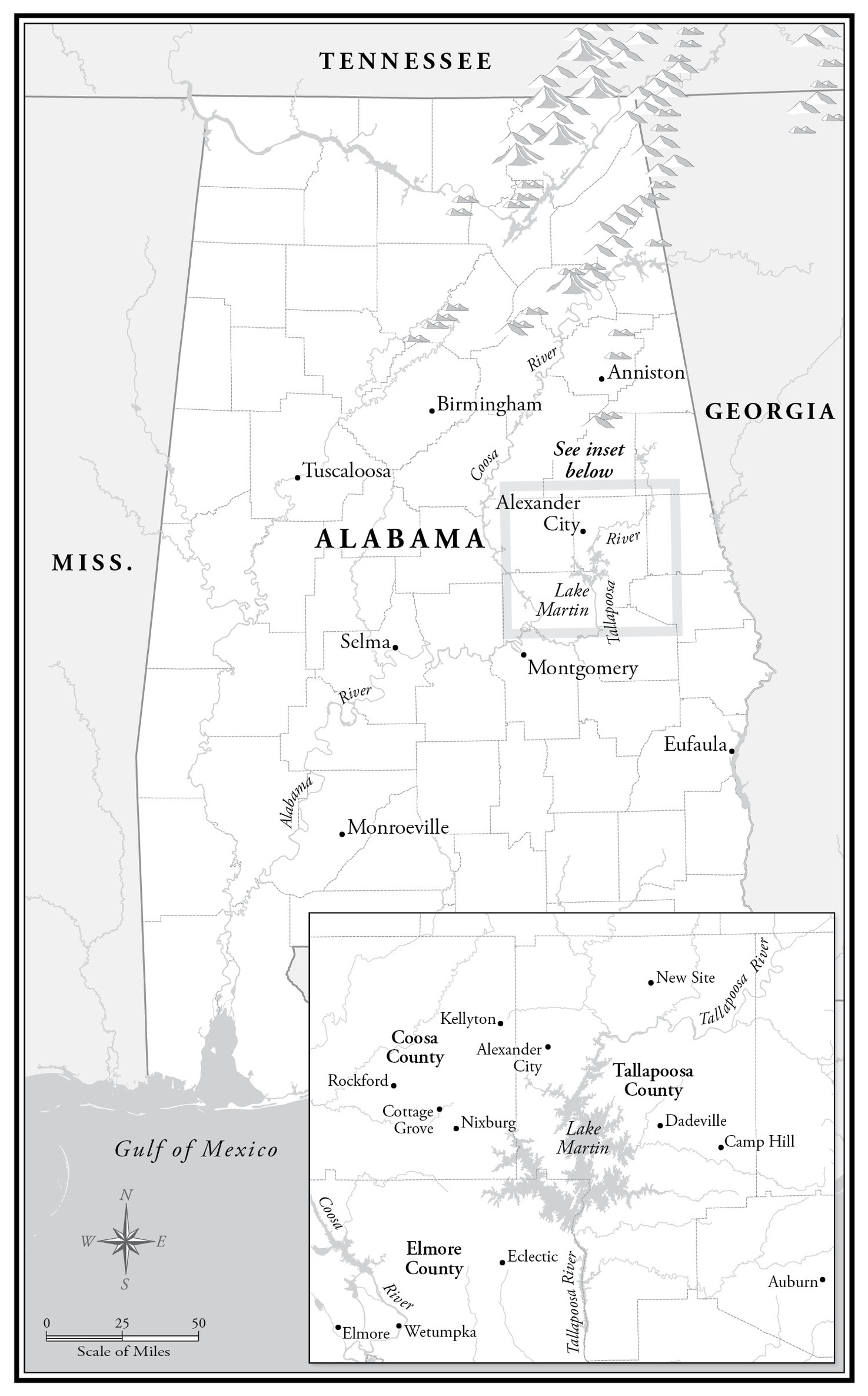

Map by Mapping Specialist, Ltd.

v5.4

ep

For my father and my mother,

who gave me a pocket watch,

then taught me to tell time

and everything else

We are bound by a common anguish.

Harper Lee

| Contents |

| Prologue |

Nobody recognized her. Harper Lee was well known, but not by sight, and if she hadnt introduced herself, its unlikely that anyone in the courtroom would have figured out who she was. Hundreds of people were crowded into the gallery, filling the wooden benches that squeaked whenever someone moved or leaning against the back wall if they hadnt arrived in time for a seat. Late September wasnt late enough for the Alabama heat to have died down, and the air-conditioning in the courthouse wasnt working, so the women waved fans while the mens suits grew damp under their arms and around their collars. The spectators whispered from time to time, and every so often they laughedan uneasy laughter that evaporated whenever the judge quieted them.

The defendant was black, but the lawyers were white, and so were the judge and the jury. The charge was murder in the first degree. Three months before, at the funeral of a sixteen-year-old girl, the man with his legs crossed patiently beside the defense table had pulled a pistol from the inside pocket of his jacket and shot the Reverend Willie Maxwell three times in the head. Three hundred people had seen him do it. Many of them were now at his trial, not to learn why he had killed the Reverendeveryone in three counties knew that, and some were surprised no one had done it soonerbut to understand the disturbing series of deaths that had come before the one theyd witnessed.

One by one, over a period of seven years, six people close to the Reverend had died under circumstances that nearly everyone agreed were suspicious and some deemed supernatural. Through all of the resulting investigations, the Reverend was represented by a lawyer named Tom Radney, whose presence in the courtroom that day wouldnt have been remarkable had he not been there to defend the man who killed his former client. A Kennedy liberal in the Wallace South, Radney was used to making headlines, and this time he would make them far beyond the local Alexander City Outlook. Reporters from the Associated Press and other wire services, along with national magazines and newspapers including Newsweek and The New York Times, had flocked to Alexander City to cover what was already being called the tale of the murderous voodoo preacher and the vigilante who shot him.

One of the reporters, though, wasnt constrained by a daily deadline. Harper Lee lived in Manhattan but still spent some of each year in Monroeville, the town where she was born and raised, only 150 miles away from Alex City. Seventeen years had passed since shed published To Kill a Mockingbird and twelve since shed finished helping her friend Truman Capote report the crime story in Kansas that became In Cold Blood. Now, finally, she was ready to try again. One of the states best trial lawyers was arguing one of the states strangest cases, and the states most famous author was there to write about it. She would spend a year in town investigating the case, and many more turning it into prose. The mystery in the courtroom that day was what would become of the man who shot the Reverend Willie Maxwell. But for decades after the verdict, the mystery was what became of Harper Lees book.

| |

Divide the Waters from the Waters

Enough water, like enough time, can make anything disappear. A hundred years ago, in the place presently occupied by the largest lake in Alabama, there was a region of hills and hollers and hardscrabble communities with a pretty little river running through it. The Tallapoosa River forms where a creek named McClendon meets a creek named Mud, after each of them has trickled down from the Appalachian foothills of Georgia. Until it was dammed into obedience, the Tallapoosa just kept on trickling from there, lazing downward until it met its older, livelier sibling, the Coosa River, near the town of Wetumpka, where together the two streams became the Alabama River, which continued westward and southward until it spilled into Mobile Bay, and from there into the Gulf of Mexico. For 265 miles and millions of years, the Tallapoosa carried on like that, serenely genuflecting its way to the sea.

What put an end to this was power. Mans dominion over the earth might have been given to him in Genesis, but he began acting on it in earnest in the nineteenth century. Steam engines and steel and combustion of all kinds provided the means; manifest destiny provided the motive. Within a few decades, humankind had come to understand nature as its enemy in what the philosopher William James called, approvingly, the moral equivalent of war. This was especially true in the American South, where an actual war had left behind physical and financial devastation and liberated the enslaved men and women who had been the regions economic engine. No longer legally able to subjugate other people, wealthy white southerners turned their attention to nature instead. The untamed world seemed to them at worst like a mortal danger, seething with disease and constantly threatening disaster, and at best like a terrible waste. The numberless trees could be timber, the forests could be farms, the malarial swamps could be drained and turned to solid ground, wolves and bears and other fearsome predators could be throw rugs, taxidermy, and dinner. And as for the rivers, why should they get to play while people had to work? In the words of the president of the Alabama Power Company, Thomas Martin, Every loafing stream is loafing at the public expense.