Contents

Guide

A LSO BY S TEPHEN B UDIANSKY

BIOGRAPHY

Mad Music: Charles Ives, the Nostalgic Rebel

HISTORY

Code Warriors

Blacketts War

Perilous Fight

The Bloody Shirt

Her Majestys Spymaster

Air Power

Battle of Wits

NATURAL HISTORY

The Character of Cats

The Truth About Dogs

The Nature of Horses

If a Lion Could Talk

Natures Keepers

The Covenant of the Wild

FICTION

Murder, by the Book

FOR CHILDREN

The World According to Horses

O LIVER

W ENDELL

H OLMES

A Life in War, Law, and Ideas

STEPHEN BUDIANSKY

Copyright 2019 by Stephen Budiansky

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Maps by Dave Merrill

Book design by Helene Berinsky

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Budiansky, Stephen, author.

Title: Oliver Wendell Holmes : a life in war, law, and ideas / Stephen Budiansky.

Description: New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018054671 | ISBN 9780393634723 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Holmes, Oliver Wendell, Jr., 1841-1935 | JudgesUnited StatesBiography. | United States. Supreme CourtOfficials and employeesBiography.

Classification: LCC KF8745.H6 B83 2019 | DDC 347.73/2634 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018054671

ISBN: 9780393634730 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

CONTENTS

To have doubted ones own first principles is the mark of a civilized man.

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES JR.

O LIVER W ENDELL H OLMES

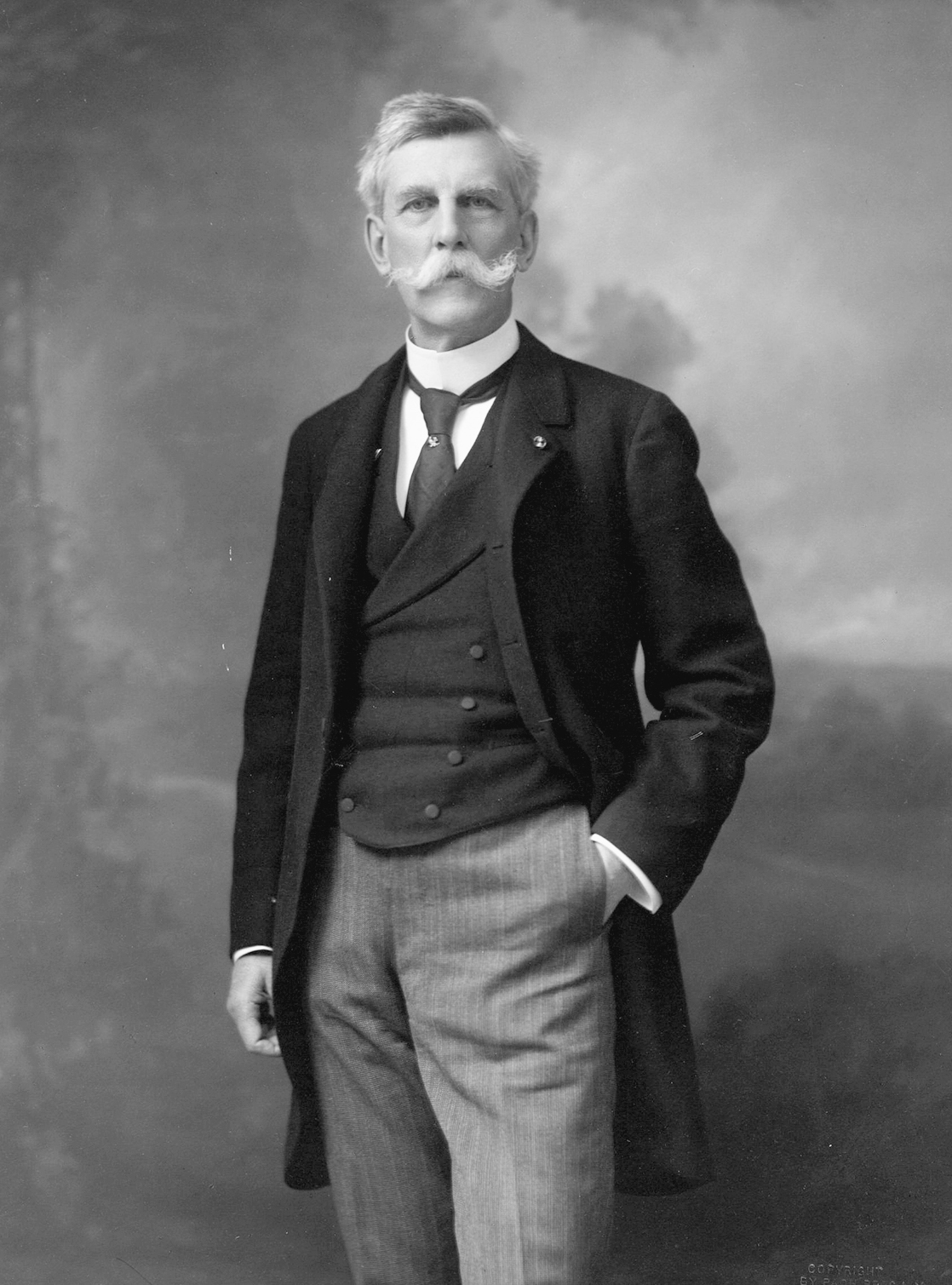

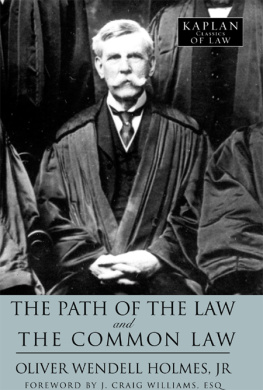

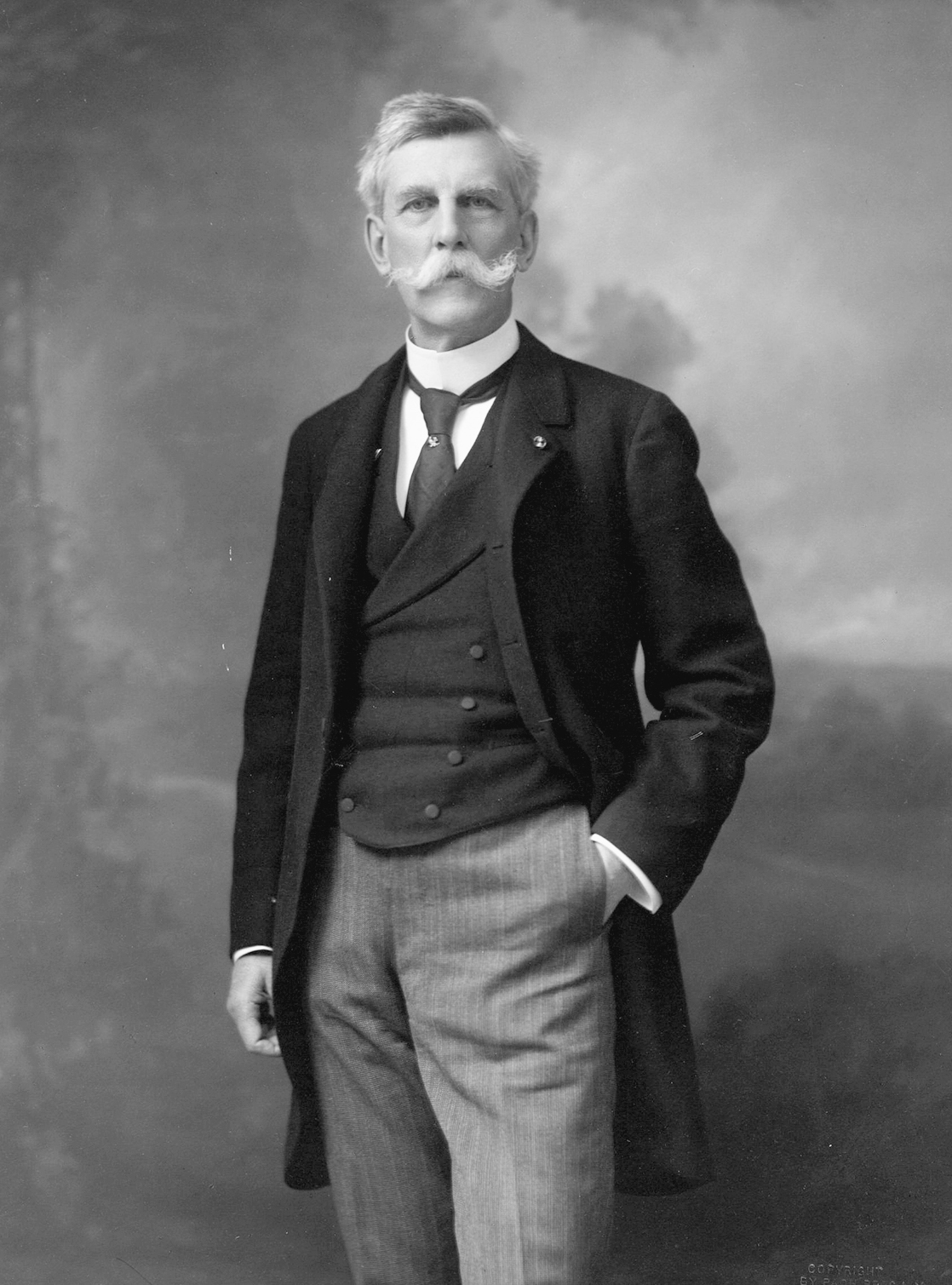

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Washington, 1914

A s he approached his seventy-fifth year in the winter of 1916, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes of the United States Supreme Court was almost as recognizable a sight to tourists wandering the nations capital as the Washington Monument or the Smithsonian Institution.

Every afternoon, when the Court was in session, the justice would walk back from the Capitol to his brownstone at 1720 I Street, just west of the White House. Impeccably dressed in the manner of the perfect Edwardian gentleman, he cut a commanding figure as he briskly strode his daily two miles home: his six-foot-three frame held erect like the soldier he had once been, magnificent white moustaches like a cavalry colonels, always turned out in formal top hat, high wing collar, cutaway coat, and striped trousers purchased from the best shops in London on his frequent visits there.

He reported to friends his facetious relief that he had so far escaped being referred to in any of the newspaper articles about his upcoming birthday as the venerable juristwhich is the sacramental phrase. He was one of those rare men who had actually grown more handsome with age, possessed of a full head of white hair, blue eyes that shone with undiminished intenseness beneath bushy brows, and a beautiful baritone voice that carried the now vanished patrician mid-Atlantic accent that ordinary Americans would become familiar with from Franklin D. Roosevelts fireside chats.

Dean Acheson recalled the arresting impression he made upon him at their first meeting, just after Achesons arrival in Washington to take up his position as Justice Louis D. Brandeiss legal secretary. Possessed of a grandeur and beauty rarely met among men, observed Acheson, his presence entered a room with him as a pervading force.

There were certainly no hints of his slowing down. I... most of the time feel as I did fifty years ago, he told the American diplomat Lewis Einstein, one of his many considerably younger friends, except that I am much happier. He still bounded up the stairs to his study two at a time and still began each day with a bracing cold batha practice he carried on until age eighty-eight, when he finally gave it up in favor of a warm bath at bedtime.

To the young lawyers in Washington for whom he always had time for a jaw, regaling them with a sparkling stream of talk about philosophy, law, and literature, his wit ever at the ready to skewer the pomposities and self-delusions of men, the years vanished altogether. It could never to occur to a younger man that he was not talking to one of his own age, said one acquaintance forty years his junior. Charlie Curtis recalled how as a student at Harvard Law School in 1916 he had been invited to tea with Holmes, and at once found himself so deep in a lively conversation thatto his horror as he replayed the scene in his mind on the way homehe was telling the justice what the law was. Curtis caught himself just as he was about to tap the great man on the knee to emphasize a point.

As oft noted as the justices mental and physical vigor was his extraordinary embodiment of the sweep of history. As a Union officer in the Civil War he had barely escaped death at Balls Bluff and Antietam when musket balls tore through his chest and neck, missing heart, spine, and carotid artery by an eighth of an inch. He had spoken to Grant and shaken hands with Meade at the Battle of Spotsylvania, and seen Lincoln dodge enemy fire at Fort Stevens during Jubal Earlys raid on Washington. As a boy he knew Ralph Waldo Emerson as a family friend and dimly remembered Herman Melville, a summer neighbor, as a rather gruff taciturn man. Traveling Europe after the war, he climbed the Alps with Leslie Stephen, better known to later generations as the father of Virginia Woolf; while in law school he became fast friends with Henry James and his brother William, soon to become, respectively, the novelist and philosopher of their generation. To Holmes they were Harry and Bill. On visits to England he met the young Winston Churchill and the old Anthony Trollope; in Washington, Bertrand Russell stopped by more than once to talk philosophy.

A quiz show in the 1960s posed the question, Which American met, during his lifetime, both John Quincy Adams and Alger Hiss? The answer of course was Holmes, who had met the sixth president of the United Statesanother family friend of his Boston boyhoodwhen he was five years old, and who had employed the future Soviet spy as one of his last law secretaries in 1929.

But it was the Civil War that was his touchstone. I hate to read about those days, he told friends; he had no interest in reliving the wars squalid preliminaries, or the blunders and worse of its battles.

Yet he was keenly alive to the wars lasting meaning for him , the profound way those terrible and ennobling experiences of youth had shaped his life. A drive to Fort Stevens was always part of the program for out-of-town visitors and for each years new secretary. He marked each anniversary of his brushes with death by solemnly drinking a glass of wine to the living and the dead, and never failed, when writing a letter or postcard to a friend around those dates, to note the occasion:

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Washington, 1914

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Washington, 1914