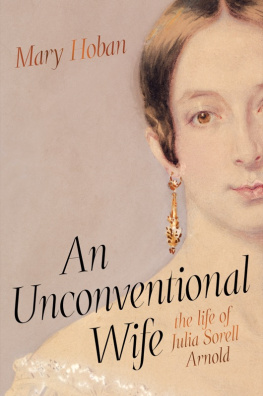

AN UNCONVENTIONAL WIFE

Mary Hoban is a Melbourne-based writer and historian. Her first book was a history of Melbournes celebrated Queen Victoria Market. She has also authored, co-authored, and edited various textbooks, papers, and journal articles in Australian and Asian history and cultural studies. For some years she was employed in the philatelic section of Australia Post as a writer, editor, and researcher for the nations postage stamps, where she wrote and edited books on subjects ranging from Christmas Island to the Antarctic, from royalty to rugby. She holds a graduate diploma in biography and life writing from Monash University and an MA in public history from the University of Technology, Sydney. In 2012 she was awarded the inaugural Hazel Rowley Literary Fellowship to write the biography of Julia Sorell Arnold.

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409 USA

Published by Scribe 2019

Copyright Mary Hoban 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Excerpt from Jimmy and I in Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, translated by Katrina Dodson, 2015 Heirs of Clarice Lispector, 1951, 1955, 1960, 1965, 1978, 2010, 2015. Translation Katrina Dodson, 2015. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.

While care has been taken to trace and acknowledge copyright, we tender apologies for any accidental infringement where copyright has proved untraceable and we welcome information that would redress the situation.

The author acknowledges with gratitude the assistance provided by the Hazel Rowley Literary Fellowship.

9781925713442 (Australian edition)

9781912854387 (UK edition)

9781947534827 (US edition)

9781925693539 (e-book)

CiP records for this title are available from the National Library of Australia and the British Library.

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com

To my mother

Contents

Mama, before she got married, according to Aunt Emilia, was a firecracker, a tempestuous redhead, with thoughts of her own about liberty and equality for women. But then along came Papa, very serious and tall, with thoughts of his own too, about liberty and equality for women. The trouble was in the coinciding subject matter.

CLARICE LISPECTOR, JIMMY AND I (1941)

Introduction

I discovered Julia Sorell Arnold in the pages of her grandsons memoirs. He was the renowned English scientist and first director-general of UNESCO, Sir Julian Sorell Huxley. She is a fleeting presence in his book, but nonetheless a startling one. On a January day in Hobart in 1856, as her husband was being received into the Catholic Church, Julia, a staunch Protestant, collected a basket of stones, walked to the church, and smashed the windows with this protesting ammunition

These words immediately evoked a long-forgotten memory from my childhood when I too threw stones. I had joined a motley group of young Catholic kids making their feelings of rejection palpable as they tossed yonnies, or little stones, onto the roof of the building where the local Brownies were meeting. It was claimed the Brownies wouldnt accept Catholics as members. I dont remember testing the allegation, nor even being particularly interested in being a Brownie, but I did like the idea of testing my arm. No windows were in our sights, though, just the roof, and most of the yonnies didnt even carry that far, but we exorcised our demons and believed the Brownies felt our presence at their meeting.

Strangely, though, it was not the stone throwing that stood out in my memory of that day, nor even the satisfaction it engendered. Instead, it was my mothers unambiguous reprimand, rendered with utter conviction, that young ladies do not throw stones. How then, I thought, could Julia Sorell, a woman at the forefront of her society, a mother of three, have done exactly that? What drove her to behave in such a dramatic, unladylike way? What emotion was inscribed into each of her tossed stones? Was it bigotry, anger, ignorance, or something else despair perhaps? How could such a public and violent demonstration in the middle of the Victorian era be understood?

Her behaviour was too compelling to put aside, but in a world where biography has traditionally focused on quest, on achievement, on destination, how would I ever uncover the life of an ordinary woman whose oblique and private life was determined by whose daughter she was and whose wife or mother or even grandmother she became? Such lives may be the stuff of novels, but they have rarely been deemed worthy of biography. Its all very well for Virginia Woolf to call for the true history of the girl behind the counter rather than the hundred-and-fiftieth life of Napoleon or the seventieth study of Keats, but who apart from Virginia Woolf might be interested in reading it and what publisher would be brave enough to take it on? Only recently, a reviewer of a biography about Betsy Balcombe as a young girl she had shared a house with Napoleon reflected that she was, after all, a fairly insignificant character, one who had no perceptible impact or influence on the great man . Why then, he asked, was there interest in this girl? Why indeed! Seldom are the letters or papers of such people gathered in archives or recorded in newspapers or books. Almost never are their names and deeds etched onto monuments or their portraits hung on gallery walls. This absence is emblematic of a deeper reality about the lives of women, governed as they have been by the routines and rhythms of domestic life and the expectation that they be quiet, never shrill, never loud, certainly never scream or do anything that might shatter glass or disturb the peace.

I was fortunate with my stone-thrower. Julia Sorell was born in Hobart Town in 1826, the granddaughter of Lieutenant-Governor William Sorell of Van Diemens Land and Anthony Fenn Kemp, the so-called father of Tasmania. Whether he gained that name because he had eighteen children or because he was one of the wealthiest and most influential of the early white settlers is unclear. Julias marriage propelled her into one of the most eminent intellectual families of Victorian England. Her father-in-law was the renowned educationalist Thomas Arnold of Rugby School, and her brother-in-law the poet and essayist Matthew Arnold. One of her daughters became a bestselling novelist at the end of the nineteenth century, another became a suffragette and journalist, while another established a school for girls that still exists today. A granddaughter was the author Janet Penrose, who married and worked alongside one of the great historians of their generation, George Macaulay Trevelyan, while two of Julias grandsons, Julian Huxley and his brother, the novelist Aldous Huxley most famous for his dystopian novel Brave New World distinguished themselves in twentieth-century science and literature. Precisely because of these connections, many of Julias letters have been saved, and through these and other documents and biographies relating to the wider Arnold and Sorell families, it is possible to extract her from the covers of married life and to paint a portrait of a woman living through an extraordinary period, when the fields of education, science, politics, industry, feminism, and religion clashed and converged, creating a new landscape and forging profound change.

Next page