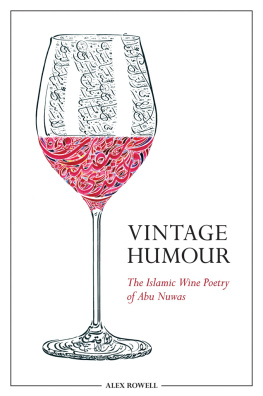

Wherever the Sound Takes You

Also by David Rowell

The Train of Small Mercies

Earlier, briefer versions of In Switzerland Nothing Is Easy, Complicated Rhythms, Going for the One, and Into the Darkness were originally published in the Washington Post Magazine. An earlier version of In Switzerland Nothing Is Easy was also previously published in Best American Travel Writing 2016 under the title Swiss Dream.

Lyrics from Do You Feel Like We Do reprinted with permission from Peter Frampton.

Lyrics from Swiss Lady reprinted with permission from Peter Reber.

Lyrics from Lesser Animal and Murder Blossom reprinted with permission from J. R. Hayes and Relapse Records.

Lyrics from Hokie Karaoke: Are You Just Another Wannabe reprinted with permission from John VanArsdall.

Lyrics from I Wanna Know, Bug, Rise Up and Fight This Shit, Nothing but Time for the Blues, Sell My Soul, Been a Long Time, Sad, Long Time, Chasm, 50 Bones, and Free (Waitin for the Rain) reprinted with permission from Bob Funck.

Lyrics to Free St. and Commercial St. reprinted by permission from Alex Milan.

Lyrics to The Toothbrush reprinted with permission from Erin Fitzpatrick.

WHEREVER THE SOUND TAKES YOU

HEROICS AND HEARTBREAK IN MUSIC MAKING

David Rowell

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47755-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-60893-8 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226608938.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rowell, David, 1958 author.

Title: Wherever the sound takes you : heroics and heartbreak in music making / David Rowell.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029033 | ISBN 9780226477558 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226608938 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: MusiciansAnecdotes. | Rock musiciansAnecdotes. | Musical instrumentsAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC ML385 .R82 2019 | DDC 781.1/7dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029033

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Lynn Medford, who let me follow the beat

All music is beautiful.

BILLY STRAYHORN

SET LIST

The Necessary Equipment

When I was young, I was under the direct influence of two people who were keenly interested in shaping my musical landscape: Bob Funck, who was two years older and lived two doors down, and my brother, John, almost six years older and one bedroom door down. My parents enjoyed music, but their record collection was a modest stack of albums by Perry Como, Doris Day, and Jim Nabors and included The Ballad of the Green Berets and the Partridge Family Christmas album. (My dad also liked bagpipe music.) Those records were played only occasionally on the curio, and mostly my parents were content to hear the music at church every Sundaythe organ, the choir, and the occasional guest trumpeter.

John was the music fanatic in the family. His great passion had formed, as far as anyone could tell, completely organically and was as instinctive as his first steps or first words. John loved show tunes. In his bedroom he sat listening, transfixed, to the original cast recordings of Man from La Mancha, The Sound of Music, and South Pacific. Most days it was as if Rodgers and Hammerstein were renting the room the next door. Its not that I disliked the musicthose classic Broadway anthems are highly tuneful and blithebut for John it was urgent that I develop the same deep reverence he had. He was constantly dragging me into his room and making me listen with him. Or he would trick me into coming in by saying he wanted to show me something, and once I stepped in hed close the door and drop the needle, and the overture from South Pacific would come streaming from his speakers.

There were no albums by rock bands in the house, though John did have a swinging record by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass Band, The Beat of the Brass, whose cover showed Alpert and his group dressed in tuxedos and looking perplexed to find themselves standing in a field of yellow flowers.

While I endured another listening of Im Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair, my friend Bob was starting to discover the progressive side of rock, thanks to his oldest sister, Roberta, the first hippie I ever knew. Bob had access to Robertas ample collection of albums and eight-tracks, including Pink Floyd, Yes, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. (She had painted the cover of Rushs Fly by Nightone of the few rock album covers to feature an intimidating owland hung it on the wall outside her room, which featured a bead curtain for a door.) Bob and I sat in his dim room and listened for hours. There was so much great music to absorb, and for me, the albums liner notes conveyed information far more interesting than what I was learning in school. We discovered, for example, that Robert Plant was the only member of Led Zeppelin who didnt have a credit on Moby Dick and that on Yess triple live album Yessongs, drummer Bill Bruford played on only three of the tracks whereas newcomer Alan White was on all the others. For me, why Richard Nixon was kicked out of office was of minor consequence, but what could have possibly happened to make Bill Bruford leave Yes?

Looking back at that time, that essential education I was getting at his house, Bob told me recently, I felt like I was giving you something important, like I had something to offer, a purpose.

When I entered seventh grade, my school created its first concert band. By that point my love for rock music was in full bloom, but I had never given any thought to actually playing music myself. There was a ukulele in our house that stayed untouched, and a bugle John had picked out with his accumulation of S&H Green Stamps that only I sometimes tried. (The sound I was able to produce was as musical as if Id blown into a chest of drawers.) We had an upright piano, and John took lessons, but to the consternation of my mother I somehow managed to avoid them. Still, I was intrigued enough to show up at the band sign-up table that first week of school. Maybe it was Herb Alpert I was thinking of when I said I wanted to try trumpet. But the band director, a peppy man with a moustache straight out of CBSs Cannon, told me that because I had braces, I wouldnt be able to perform a proper embouchure to play it. I took a few seconds to think about that, then asked, How about the drums? It would be one of the most significant choices I ever made.

I was issued a large plastic suitcase that held a chrome Premier concert snare as well as a small xylophone. I dragged it home and began to bang on my new instruments.

It turned out that I had a natural aptitude for drumming. I loved how the drumstick felt as it bounced against the snare headthat little jolt of friction against my palmand drum rolls came relatively easily. For me, learning to read music was like learning geometry: I displayed no genius for it, but I understood the shapes, the calculation of spaces, and the particular sizes well enough to do the work required. At the end of the year I won the schools first Excellence in Band award, which stunned meand my bandmates. This rare bit of success was far from my areas of expertise, Atari games and

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).