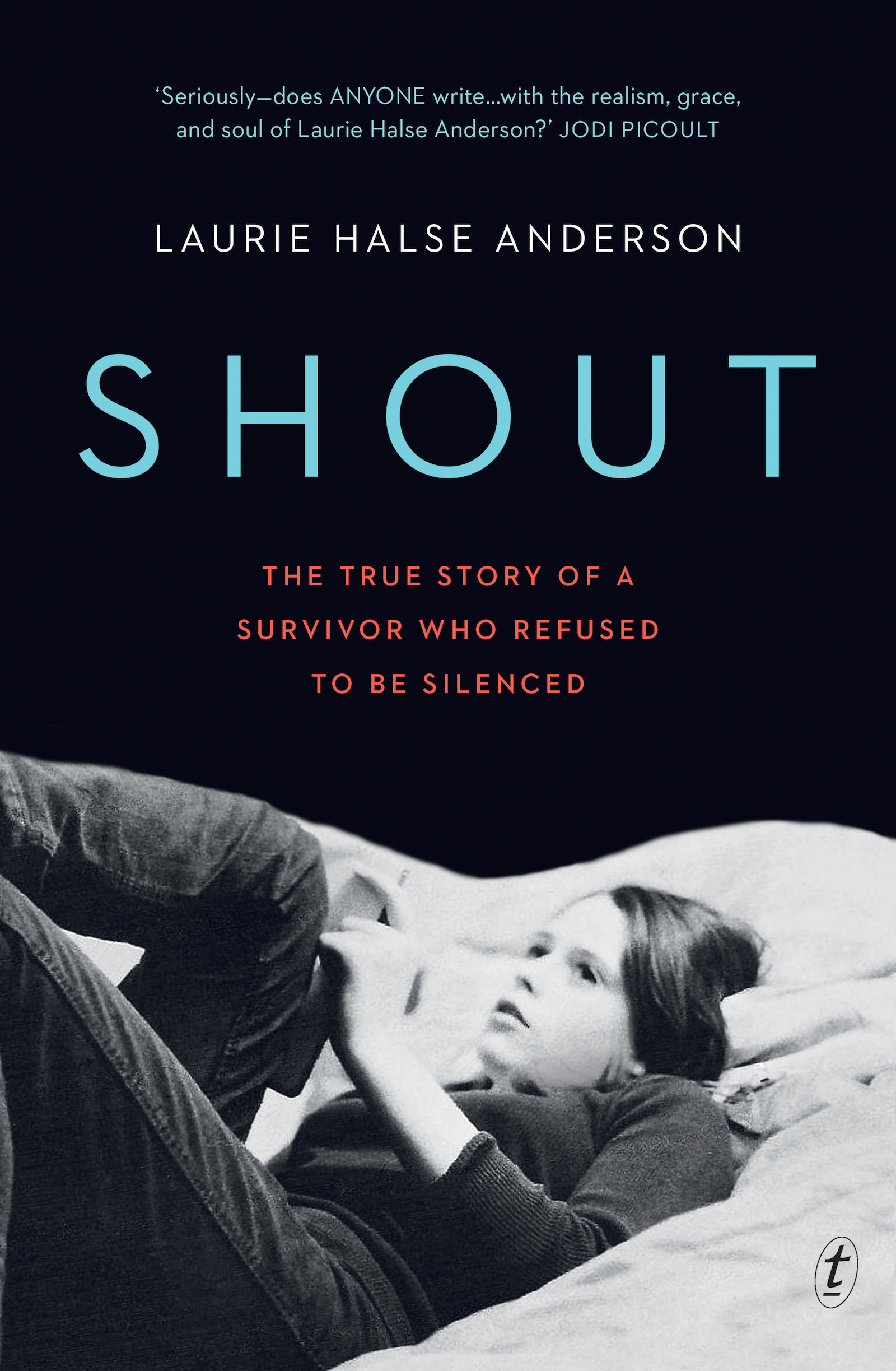

When she was thirteen years old, Laurie Halse Anderson was raped by a boy she trusted.

Twenty-five years later, she published her first novel, Speak, the story of a girl dealing with the trauma of rape, which became a New York Times bestseller and sparked her advocacy and activism for sexual assault survivors.

Now, inspired by the harrowing experiences of so many of her readers and enraged by how little in our culture has changed, she has written a deeply personal account of her own experience and how she turned her pain into art that would go on to help millions of readers the world over.

Searing and soul-searching, Shout is a profound memoir that speaks truth to power in a loud, clear, inspiring voice.

Contents

for the survivors

Finding my courage to speak up twenty-five years after I was raped, writing Speak, and talking with countless survivors of sexual violence made me who I am today.

This book shows how that happened.

Its filled with the accidents, serendipities, bloodlines, tidal waves, sunrises, disasters, passport stamps, criminals, cafeterias, nightmares, fever dreams, readers, portents, and whispers that have shaped me so far.

My father wrote poetry, too. He gave me these guidelines: we must be gentle with the living, but the dead own their truth and are fearless. So Ive written honestly about the challenges my parents faced and how their struggles affected me. The poems that reference people other than me or my family are truth told slant; Ive muddled specific details to protect the identities of survivors.

This is the story of a girl who lost her voice and wrote herself a new one.

this book smells like me woodsmoke salt honey and strawberries sunscreen, libraries failures and sweat green nights in the mountains cold dawns by the sea

this book reeks of my fear of depressions black dogs howling and the ancient shames riding my back, their claws buried deep

this book is yesterdays mud dried on the dance floor the step patterns cautiously submitted for your curious investigation of what I feel like on the inside

When he was eighteen years old, my father saw his buddys head sliced into two pieces, sawn just above the eyebrows by an exploding brake drum, when he was in the middle of telling a joke.

Repairing planes, P-51s, on an air base in England, hungry for a gun, not a wrench, my father pushed an army-issue trunk into his mind and put the picture of his friends last breath at the bottom of it.

Then they sent him to Dachau. Not just him, of course, his whole unit, and not just to Dachau, but to all of the camps because the War was over. But not really.

Daddy didnt talk to me for forty years about what he saw, heard, what he smelled what he did about it; one year of silence for every day of the Flood, one year for every day from Lent until Easter.

The air in Dachau was clouded with the ash from countless bodies, as he breathed it in the agony of the dying infected my father, and all of his friends. They tried to help the suffering, followed orders, took out their rage in criminal ways while their officers turned away. My father filled the trunk in his head with walking corpses who sang to him every night for the rest of his life.

One day Daddy watched a pregnant woman walking slowly down the road near the gates of Dachau he matched his steps to hers, then stopped as she crouched in a ditch and birthed a baby.

My father, a kid on the verge of destruction, half-mad from the violence hed seen desperate to kill, to slaughter, to maim, watched that baby slip into the world between her mommas blood-slicked thighs and it healed him just enough that he wept.

He wrapped the newborn in her mothers apron and helped them both to the Red Cross tent set up for survivors.

Veteran of D/depression, the German war and atrocities a handsome boy married the tall girl who looked like Katharine Hepburn two kids adrift in a city far from home two ships ripped from their moorings.

Mom told me the story when I was in high school, on a night when Daddys drinking drove our family to the edge He had to slap me, she said. It happened before you were born.

The image of my father hitting my mother picassoed in front of me like Sunday sunshine slicing through the church windows, fracturing and rearranging the truth on the floor.

They lived in Boston back then Daddy studying to be a preacher

Mom trying to be a wife. He had to slap me, she repeated. I was screaming, screaming for reasons too many to count.

The full story came out in gingerbread crumbs dropped to show me the way.

After the meltdown, the attack, they had to ride the train home to repair the damage to her face home to the mountains, to their parents to a clucking village of spite, her broken teeth vibrating in bloody sockets, her husband horrified at the war hed declared on his beloved, he turned toward the aisle thinking of escape.

Her backbone crumbling under the weight of her heart, she fixed her eyes on the dark forest just beyond the glass. I wouldnt shut up, she said. He had to.

The lie told to friends was that she fell, clumsy, tumbled down the stairs so many broken teeth, poor thing bad things happen in big cities, you know.

The truth was that the stress of fighting the ghosts in his head broke him that night and as they argued my father didnt just slap my mother. He beat her. But beatings didnt fit in the fairy tales she liked to tell herself so she sugarcoated the story to make it easier to swallow.

The town dentist, a family friend, didnt charge for his labor gently apologized with every tooth. They lived with her parents all summer while her mouth healed, waiting for the false teeth, they tiptoed but they did not touch.

After the stitches came out after she learned to mix tooth powder with water to make the glue that held her mouth together, after five miscarriages, five never-born sons, my parents tried again and created me. He didnt ever hit her again, but she lived in the fear that he would, which had everything to do with her habits of silence.

I said shit in front of the church ladies gathered in our kitchen for coffee and doughnuts, three-year-old me: the potato-shaped, sturdy-legged parrot-tongued echo chamber

I fell down, scraped my knee, and said shit in frustration, the word I had learned from my mother crammed and dammed into the corseted life of a ministers wife where she couldnt say shit if she had a mouthful.

But alone, with me, she could, and did frequently.

That day in the kitchen, as the church ladies eyed my mothers handmade curtains, measuring her skills, I baby-cursed and was snatched from the floor.

Shoving a bar of soap into the mouth of a child was then a common practice, church lady approved, for scrubbing dirty words from the minds of the young, the violence of generational silence brutally handed down.

Ivory grooves deep-carved in the bar by my baby teeth Mommys bruising fingers pinning me against the sink

My sobs captured in bubbles heard only after they popped, after I was jailed in my room and the ladies of the church and my mother sipped bitterness and shared crumbs.

I learned then that words had such power some must never be spoken and was thus robbed of both tongue and the truth.

My mother took me to a pond when I was four years old for swimming lessons. There was a beach, of sorts, littered with pine needles and mothers smoking cigarettes on towels, wearing sweaters and warm socks; summer in the North Country.