CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people, scattered from the jungles of Ecuador to the skyscrapers of New York, have helped in the writing of this story. The four other widows, Barbara Youderian, Marj Saint, Marilou McCully, and Olive Fleming, when they suddenly found themselves with doubled responsibility, took time to gather their husbands' diaries, letters, and other writings, and were willing to share them. Abe C. Van Der Puy, of the missionary radio station HCJB in Quito, Ecuador, spent many months assembling material for The Reader's Digest article, prepared by Clarence W. Hall, which appeared in the issue of August 1956. I have freely drawn on this material in the expanded version of the story. Cornell Capa, of Magnum Photos, flew to Ecuador for Life magazine within hours after the news of the martyrdom of the missionaries was radioed to the American press. With his perceptive and sensitive pictures, he tells a story which words could not have told. His skillful guidance could not have been bought with money. Life has generously made available the photographs taken for them by Cornell Capa. Jozefa Stuart, of the Magnum research staff, made a special trip to Ecuador for the publishers to collect extensive additional data which I needed in writing the book. Many of the facts on the Auca Indians came from Rachel Saint, sister of the missionary pilot, who learned them from an escaped member of the tribe. Nate Saint's brother Sam played a unique role as adviser and official representative for the five of us widows. Decisions which would have been beyond our ability to make, Sam made, consulting with us by overseas telephone, personal conference, and mail. The hours and the miles of travel he devoted on our behalf cannot be counted. The editors of Harper & Brothers were unstinting in giving of themselves to make this book what it ought to be. Their counsel and encouragement have been invaluable. To all of these people I am deeply grateful. With Barbara, Mad, Marilou, and Olive, I thank God for allowing us to share so intimately in the lives recorded in these pages. And to Him who made them what they were, we repeat the words which our husbands sang a few days before they died:

"We rest on Thee, our Shield and our Defender, Thine is the battle, Thine shall be the praise When passing through the gates of pearly splendor Victors, we rest with Thee through endless days. "

Elisabeth Elliot

Quito, Ecuador

February, 1957

CHAPTER I

"I Dare Not Stay Home"

The Santa Juana is under way. White stars breaking through a high mist. Half moon. The deep burn of phosphorus running in the wake. Long, easy rolling and the push of steady wind."

It was hot in the little cabin of the freighter. Jim Elliot, who was later to become my husband, was writing in the old cloth-covered ledger he used for a diary. It was a night in February, 1952. Pete Fleming, Jim's fellow missionary, sat at a second desk. Jim continued:

"All the thrill of boyhood dreams came on me just now outside, watching the sky die in the sea on every side. I wanted to sail when I was in grammar school, and well remember memorizing the names of the sails from the Merriam-Webster's ponderous dictionary in the library. Now I am actually at sea-as a passenger, of course, but at sea nevertheless-and bound for Ecuador. Strange-or is it?-that childish hopes should be answered in the will of God for this now?

"We left our moorings at the Outer Harbor Dock, San Pedro, California, at 2:06 today. Mom and Dad stood together watching at the pier side. As we slipped away Psalm 60:12 came to mind, and I called back, 'Through our God we shall do valiantly.' They wept some. I do not understand how God has made me. Joy, sheer joy, and thanksgiving fill and encompass me. I can scarcely keep from turning to Pete and saying, 'Brother, this is great!' or 'We never had it so good.' God has done and is doing all I ever desired, much more than I ever asked. Praise, praise to the God of Heaven, and to His Son Jesus. Because He hath said, 'I will never leave thee nor forsake thee,' I may boldly say, I will not fear....' "

Jim Elliot laid down his pen. He was a young man of twenty-five, tall and broad-chested, with thick brown hair and blue-gray eyes. He was bound for Ecuador-the answer to years of prayer for God's guidance concerning his lifework. Some had thought it strange that a young man with his opportunities for success should choose to spend his life in the jungles among primitive people. Jim's answer, found in his diary, had been written a year before:

"My going to Ecuador is God's counsel, as is my leaving Betty, and my refusal to be counseled by all who insist I should stay and stir up the believers in the U.S. And how do I know it is His counsel? 'Yea, my heart instructeth me in the night seasons.' Oh, how good! For I have known my heart is speaking to me for God! ... No visions, no voices, but the counsel of a heart which desires God."

Jim's mood of the moment was felt by Pete. Pete was shorter than Jim with a high forehead and dark wavy hair. The two had learned to understand and appreciate each other long before, and their going to Ecuador together was, to them, one of the "extras" that God threw in. Pete, too, had met with raised eyebrows and polite questions when he made it known that he was going to Ecuador. An M.A. in literature, Pete was expected to become a college professor or Bible teacher. But to throw away his life among ignorant savages-it was thought absurd.

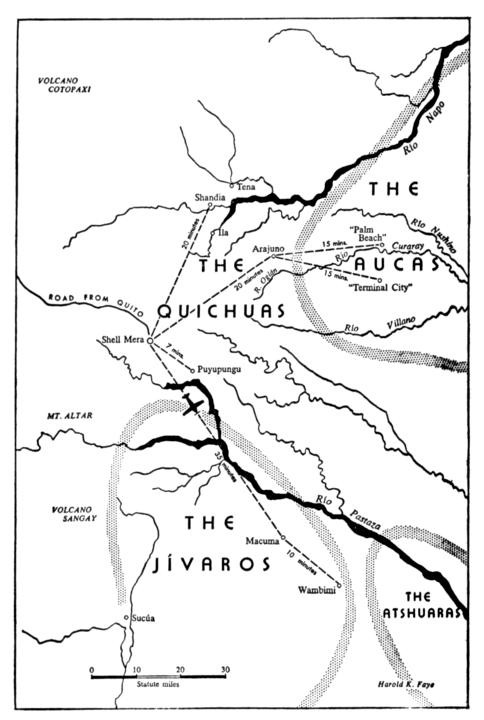

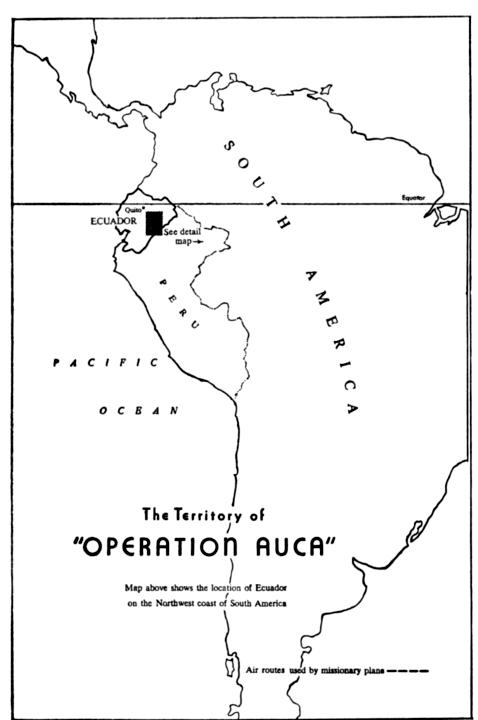

Only a year or two before, the problems of Ecuador, on the northwest bulge of South America, had seemed remote. The two young men had talked with several missionaries who had been there, who described the enormous problems of transportation, education, and development of resources. Missionary work had done much to help the country bridge the cultural span of a millennium between primitive jungles and modern cities. But progress was pitifully slow. Evangelicals had been working among the head-shrinking Jivaros for twenty-five years, among the Quichuas of the high Andes, and among the red-painted Colorados of the western forest. The Cayapas of the northwestern river region had also been reached with the Gospel, and advances were soon to be made into the Cofan tribe of the Colombian border.

But there remained a group of tribes that had consistently repelled every advance made by the white man: the Aucas. They are an isolated, unconquered, seminomadic remnant of age-old jungle Indians. Over the years, information about the Aucas has seeped out of the jungle: through adventurers, through owners of haciendas, through captured Aucas, through missionaries who have spoken with captured Aucas or Aucas who have had to flee from killings within the tribe. Whatever Jim and Pete had been able to learn about them was eagerly recorded, so that by now the very name thrilled their young blood. Would they someday be permitted to have part in winning the Aucas for Christ?