FURTHER PRAISE FOR Fault Lines

The son of a very wealthy and highly assimilated Jewish woman from Central Europe and a famous English literary intellectual whose homosexuality his wife never allowed herself to admit, David Pryce-Jones, now grown into a distinguished literary intellectual in his own right, has an extraordinary story to tell, and he tells it in endlessly fascinating detail.

N ORMAN P ODHORETZ

former longtime editor of Commentary and author of several memoirs, including Making It and Ex-Friends

One of the most passionate and beguiling books on inheritance since Gosses Father and Son. This is a story of a family of almost unimaginable wealth and privilege, of an extraordinary life lived across literary and political worlds, and of a century backlit by war and trauma. It has a candour, a humour and a fierce intelligence that make it a powerful and remarkable book.

E DMUND DE W AAL

author of The Hare With Amber Eyes

Fault Lines

David Pryce-Jones

Copyright 2015 by David Pryce-Jones

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Criterion Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 602, New York, NY 10003.

First American edition published in 2015 by Criterion Books, an activity of the Foundation for Cultural Review, Inc., a nonprofit, tax exempt corporation.

Criterion Books website: www.newcriterion.com/books

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Pryce-Jones, David, 1936

Fault lines / David Pryce-Jones.

pages; cm

Summary: Born in Vienna in 1936, David Pryce-Jones is the son of the well-known writer and editor of the Times Literary Supplement Alan Pryce-Jones and Therese Poppy Fould-Springer. He grew up in a cosmopolitan mix of industrialists, bankers, soldiers, and playboys on both sides of a family, embodying the fault lines of the title: not quite Jewish and not quite Christian, not quite Austrian and not quite French or English, not quite heterosexual and not quite homosexual, socially conventional but not quite secure. Graduating from Magdalen College, Oxford, David Pryce-Jones served as Literary Editor of the Financial Times and the Spectator, a war correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, and Senior Editor of National Review. Fault Lines a memoir that spans Europe, America, and the Middle East and encompasses figures ranging from Somerset Maugham to Svetlana Stalin to Elie de Rothschild has the storytelling power of Pryce-Joness numerous novels and non-fiction books, and is perceptive and poignant testimony to the fortunes and misfortunes of the present age Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-9859052-9-3 (softcover : acid-free paper)

1. Pryce-Jones, David, 1936 2. Authors, English20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PR 6066. R 88 Z 46 2015

823.914dc23

[B]

2015034142

C ONTENTS

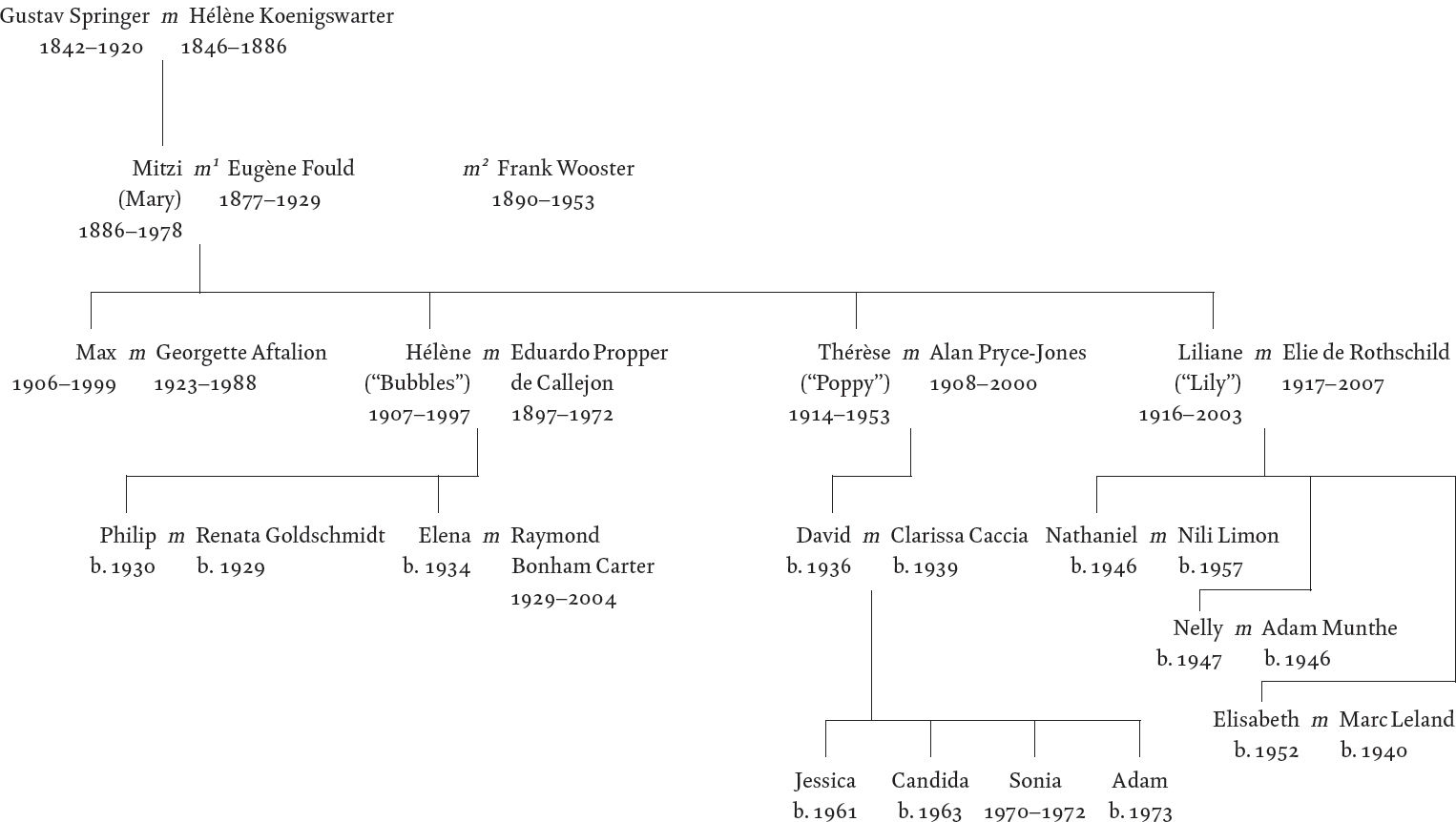

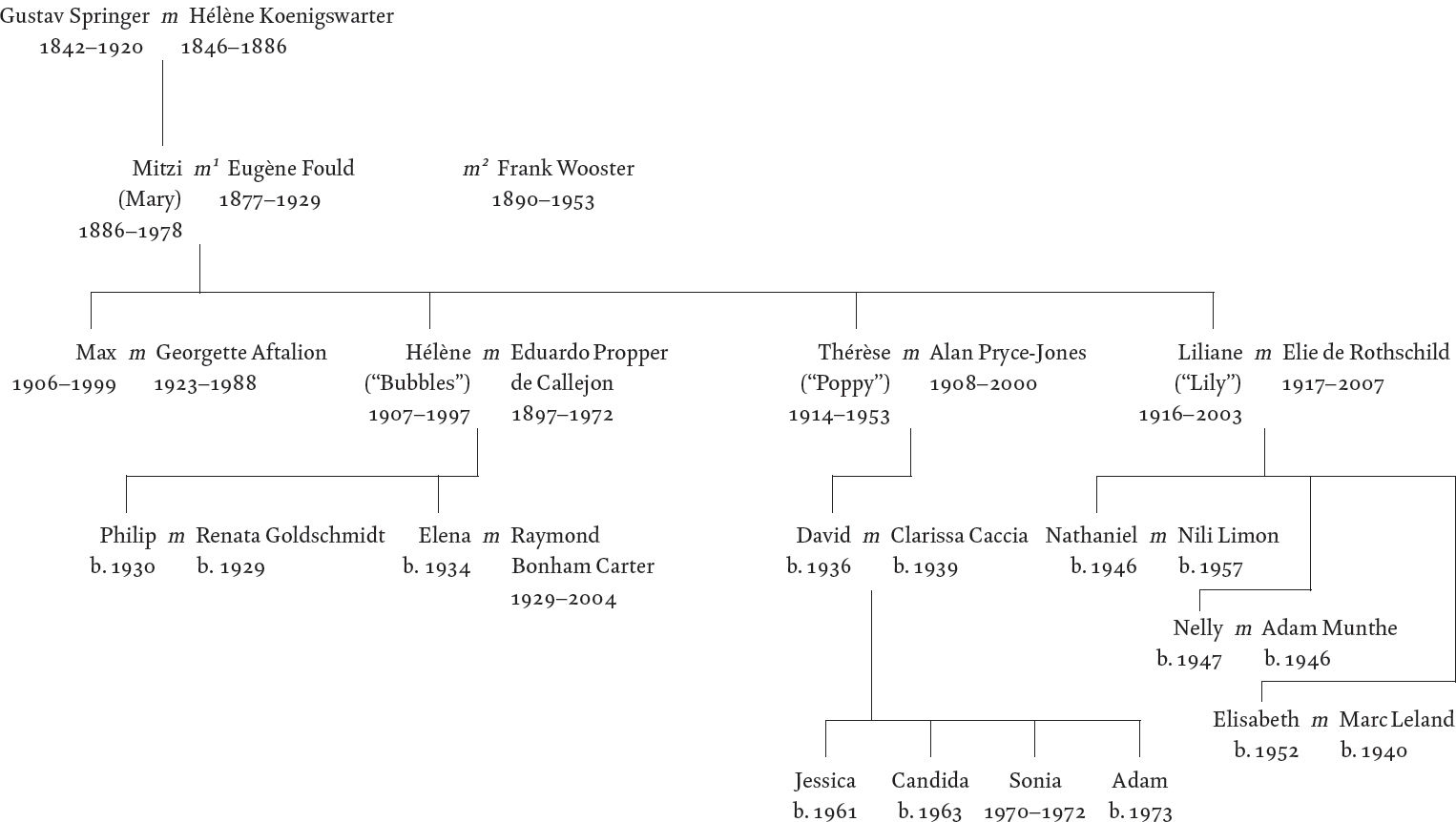

For Jessica, Candida and Adam, and in memory of Sonia

The Fould-Springer Family Tree

O NE

A Moment in Austria

I N THE FIRST DAYS of January 1953 my mother and I arrived in what was then the isolated village of Seefeld in the Tyrol. Aged thirty-seven, she was returning for the first time since before the war to the country in which she had been born and to which she had a sentimental attachment, perhaps deteriorating into some sort of love-hate relationship. Originally called Thrse Fould-Springer, she was Poppy to almost everyone who knew her before and after she made her life in England with Alan, my father. Here we were to stay in the Pension Philipp, newly built, and taking its name from the couple who owned and ran this rather modest venture in a post-war Austria still under Allied occupation and unsure of the future. My mother liked the hard-working Frau Philipp. We were there to have a holiday, and especially to ski, before I went back to Eton. An only child, I was sixteen.

My mothers younger sister Liliane had brought us to Seefeld. She had become familiar with this part of the world because her husband Elie de Rothschild had taken a lease on a shoot belonging to the Saxe-Coburgs. The lodge, a wooden chalet, was at the end of a long and twisty track that reached from the next village of Scharnitz high up into the Karwendel mountains, impassable in winter. Herr Ragg, the head keeper, a stout Father Christmas figure with red cheeks and a white beard, seemed to have survived from Habsburg days. He once corrected Elie for speaking loosely about the Austrian provinces Italy had acquired as spoils after the First War, Sud Tirol, Herr Baron. His younger son, Hubert Ragg, was our guide on the slopes, and slightly too insistent about it. A possible champion, he had lost his nerve in a bad fall while racing, and he wanted to hide it.

Aunty Lily, as she was to me, came with her two small children, my cousins Nathaniel and Nelly, and their nanny Miss Sargent from Norfolk. In Paris they lived in the Avenue Marigny, a house inherited from Elies father and one of the largest in the entire city, round the corner from the President of France in the Elyse. Thanks to Liliane, they also had a house called La Faisanderie on the Fould-Springer familys estate at Royaumont near Chantilly. The ensemble of buildings there is one of the showplaces of France. In the thirteenth century, the abbey had been built for the Cistercians by Saint Louis; the church and much else was pulled down during the French revolution, to leave a refectory, halls, and imposing monastic quarters around a cloister. This was the property of our neighbors, the Gouins, whose daughter Marie-Christine was twenty when she too was with our party in the Pension Philipp, so to speak a lifelong honorary member of our family.

On January 12 Poppy wrote to her mother, Mitzi or Mitz to those who had known her in the first part of her life, and Mary to those who had known her afterwards. My grandmother was then in her flat in Paris just behind the Madeleine within walking distance of the Rothschilds in the Avenue Marigny. French was the language in which these two corresponded, with bits of German and English as decoration. Poppys excuse for not writing sooner was that she had spent two very bad days, feeling sick with pains in her liver and kidneys. Naturally my morale responds, each time I feel better I am filled with hope but I must say that Im beginning to have more than enough of it. If I dont feel much better I may come back sooner to Paris. She proposes more consultations with her Paris specialists whom she names, Drs dAllaines, Mayer, and Camille Dreyfus. The rest of this letter is in quite another mode, cheerfully social, describing the New Years Eve she and Alan had just spent with Harry and Rosie dAvigdor-Goldsmid at Somerhill, their house on the edge of Tonbridge. It was a home from home. Until that year, we had lived in Castle Hill Farm, tenants on their estate. At Fairlawne, a country house a few miles away, lived the racehorse trainer Peter Cazalet, his wife Zara and his son Edward, exactly my age. We visited them. Staying there were Lady Margaret Douglas-Home and two of her children, Fiona and Charlie, two more friends for me. Ctait trs gemtlich Poppy writes in the familiar linguistic mix. She and Alan had completed the upheaval of moving to London and she closes this letter to her mother, what worries me most in all this is Alans agony and exhaustion and I wonder if a radical change and a simpler life might be envisaged.