For my family

CONTENTS

I have just escaped a most unpleasant death...

CAPTAIN WILLIAM LANCASTERS SAHARA DIARY

Life at its best is short anyway...

JESSIE KEITH-MILLER

PROLOGUE A TIME LIKE THIS

T he Dade County Courthouse on bustling Flagler Street in downtown Miami was the tallest building in the state of Florida. By some accounts, it was the tallest building south of Baltimore, and the tallest municipal building in the United States. Completed four years earlier, at a cost of more than four million dollars, the twenty-eight-story neoclassical structure, with its gleaming white terra-cotta exterior and distinctive ziggurat roofline, was dazzlingly lighted at night and could be seen, the rumor went, for fifty miles by land and a hundred miles by sea. The courthouse included the requisite courtrooms, judicial chambers, law library, and administrative offices, in addition to serving as Miamis City Hall. It also housed, on its top nine floors, the Miami City Jail.

The date was August 2, 1932. At a quarter past nine in the morning, the celebrated British aviator Captain William Lancaster received a guarded escort from his twenty-second-floor jail cell down to a sixth-floor courtroom to begin his long-awaited trial. Lancaster had spent the summer in captivity, charged with the murder of a Miami writer named Haden Clarke. For months the story had transfixed newspaper readers around the globe. The trial had been moved from the regular circuit courtroom to the larger criminal courtroom to accommodate the crush of expected spectators.

Hours before the court opened, hundreds of people milled about the courtroom, some jammed tightly against the door. Bailiffs could hardly move the throng to allow the forty-three witnesses and one hundred prospective jurors to enter the room. Outside the courthouse, mobs of would-be spectators fought to gain entry to the building. Women of all ages, including many with children, predominated in the crowd. Because of the international interest the case had generated, three noiseless telegraph instruments belonging to the International Press Services had been allowed in the courtroom for the first time in Dade Countys history.

Shortly before 9:30 a.m., Lancasterwearing a light brown suit, gray shirt, and tan tieentered the room in the company of his attorneys, James Carson and James Happy Lathero, both of whom were attired, like true Southern gentlemen, in white suits. Lancaster appeared relaxed, even good-humored. Behind him, a large American flag rippled in the breeze from the open courtroom windows. As he posed for photographs, the flags folds fell across his shoulders. Lancaster laughed. He dropped his lighthearted facade just long enough to ask the news correspondents to send a message to his father in England: Dont worry, everything is all rightBill. When a photographer asked him to smile, he demurred, saying, Its hard to smile at a time like this.

Garnering just as much attention from reporters that day was Mrs. Jessie Keith-Miller, Captain Lancasters longtime flying partner and lover, and one of the pioneering female aviators of the period. At the time of Haden Clarkes death by gunshot, Jessie and the young writer had been romantically involved. Now, at the courthouse, Jessie looked visibly nervous as she stood for the photographers. Her face tense, she stared straight ahead, not even the hint of a smile breaking her tightly compressed lips. The newspapers noted her slim figure, stylish white silk dress, white hat, white shoes with yellow insteps, and flesh-colored stockings.

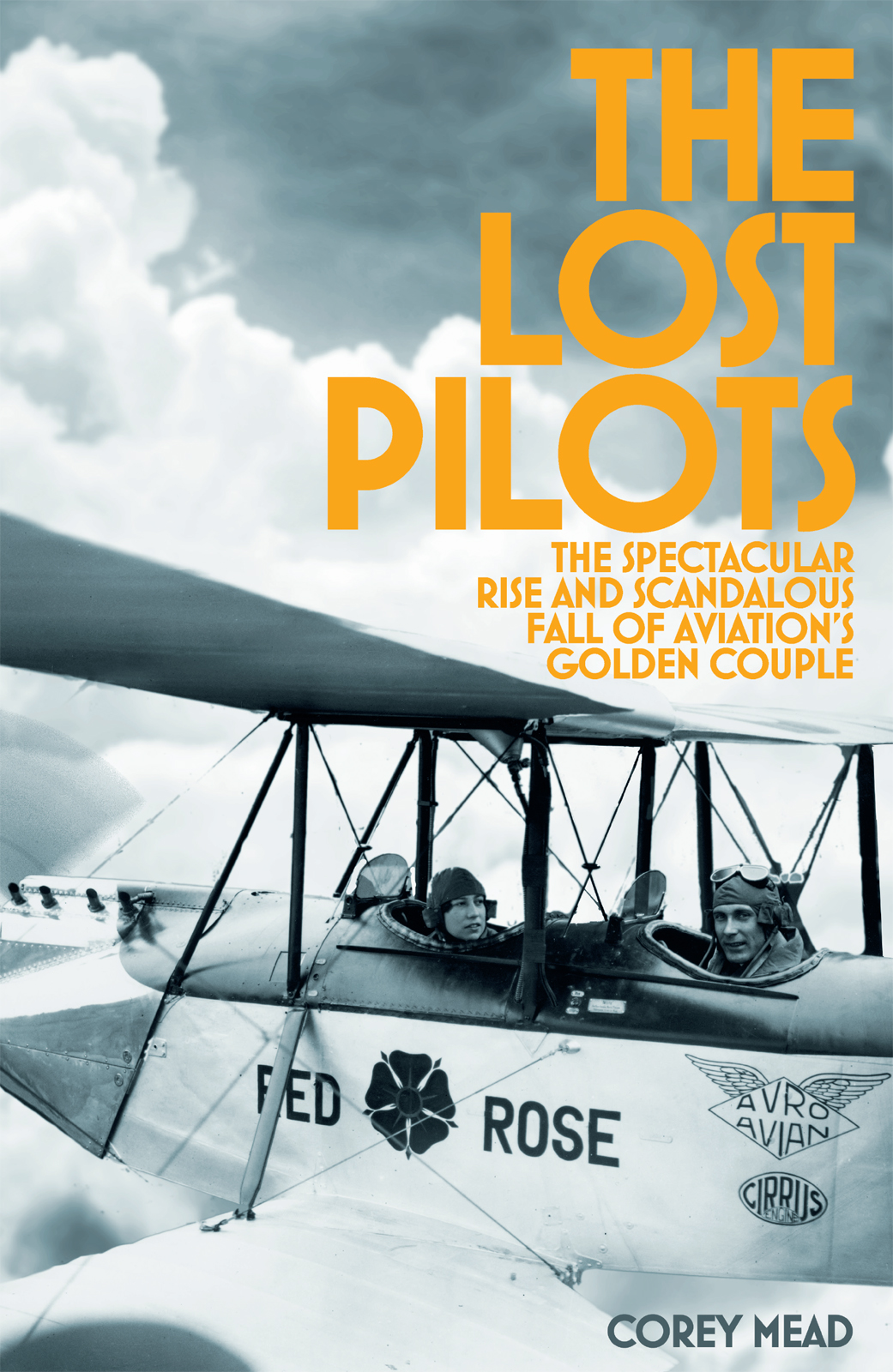

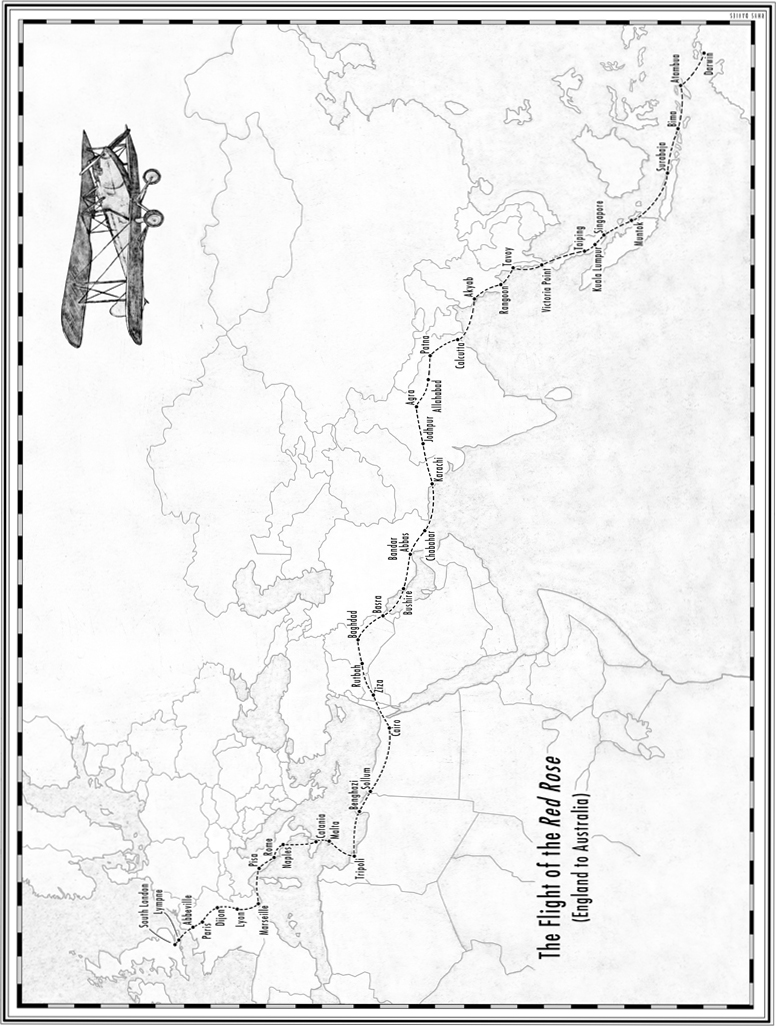

When Bill Lancaster and Jessie Keith-Miller had first met, five years earlier, they were both trapped in unhappy marriages. Over the course of a record-setting six-month flight from England to Australia, they had fallen in love. Fame and adulation had followed, leading them to America, where aviators were the newly crowned heroes of the so-called Golden Age of Aviation. But the Great Depression had dried up their fortunes, and Jessie had found comfort in the arms of another manuntil the tragedy that had led her and Lancaster to a packed Miami courthouse on a sweltering August day. Now one of the most sensational hearings in the history of Florida, as the Miami Herald dubbed it, was about to begin.

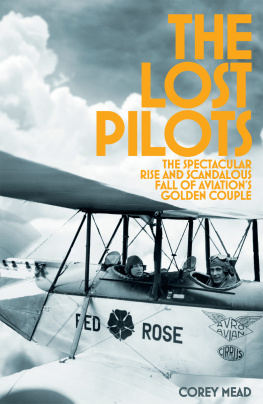

PART I RED ROSE

BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS

O n a muggy June night in 1927, a whirl of music, laughter, and conversation spilled from the open windows of an artists Baker Street studio in London. Paintings crowded the studios walls, but actual furniture was sparse, with only a low sofa, a few scattered cushions, and a single chair in which to sit. The party guests that night didnt care; as they weaved throughout the crowded, cigarette-smoke-filled room, they felt an immutable kinship with the chaos and promise of the blossoming Jazz Age. They were young women in pearls and fashionable dresses, and young men in suits, their jackets abandoned in the heat, eagerly clutching sweating tumblers of gin and tonic. They were the Bright Young Things of London, a pleasure-seeking assortment of wealthy socialites, bohemian artists, and middle-class rule-breakers, who gloried in their own irresponsibility and blissfully debauched fun. But beneath the bright, shiny facade, though they were not eager to admit it, the traumatic shadow of World War I lingered always over their frivolity, adding to it an air of desperation, a last-ditch alcohol-soaked escape from the black dog that trailed in their paths, no matter how privileged their social status and connections.

One of the party guests, a dark-haired, full-lipped twenty-five-year-old Australian woman with sparkling eyes who shared a one-room apartment downstairs, stood entranced at the scene before her, thrilled by the vitality of her newly adopted city. Jessie Keith-Millerjokingly called Chubbie by her friends, a childhood nickname that had evolved into a winking reference to her slender five-foot-one framehad arrived in London only weeks before, leaving behind Australia and a husband to whom she was unhappily married. This was her first London party, and it was filled with the kinds of glamorous, intriguing artists and bohemians who she had dreamed would fill her new life.

With the party in full swing, Jessie followed the partys host, George, around the room. He introduced her to a smattering of acquaintances, before stopping in front of a tall, lean, well-dressed man with a high forehead, thinning brown hair, and a crinkly smile. This is Flying Captain Bill Lancaster, George told Jessie. Hes flying to Australia. That should give you something in commonyou ought to get together.

Lancaster radiated geniality and good cheer, and he was in a chatty mood. In no time at all the handsome pilot was telling Jessie about his plans for an upcoming solo flight to Australia, a feat that had never been attempted with the type of light airplane he intended to fly, one that would weigh significantly less than the heavier variety of plane that previous fliers had employed. (In aviation, the terms heavy and light refer simply to an aircrafts takeoff weight.) Though the idea had been germinating for some time, Lancasters imagination had been newly fired by an event that had electrified the world just one month earlier.

On May 20, 1927, at Roosevelt Field on Long Island, Charles Lindbergh, an unknown U.S. Air Mail pilot, had climbed into his self-designed lightweight aircraft, the