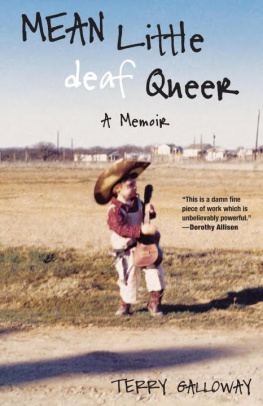

Terry Galloway - Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir

Here you can read online Terry Galloway - Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

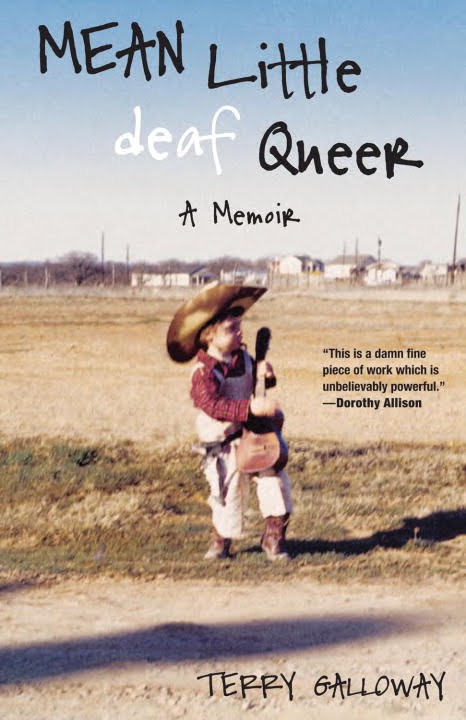

- Book:Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Mean Little deaf Queer

A Memoir

Terry Galloway

Beacon Press

Boston

For my complex and loving family:

Edna, Paul, Gail (Trudy), Tenley, Tim, my two nephews, and my truest of true loves, Donna Marie.

My sister is persistent. She wants to get the story straight, or as straight as she wants it for her own purposes.

Gail Galloway Adams, The Tellers Tale, in The Purchase of Order: Stories

Contents

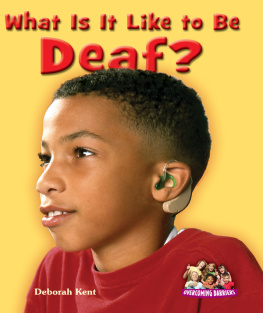

Prologue: Nine

The year I turned nine, months before anyone knew I was going deaf, the voices of everyone I loved had all but disappeared. Their chatter had been like the nattering of birds in the treesa cheerful if sometimes annoying reminder of how alive the world was around me. As their voices lapsed away, I no longer felt sure how any but the most common words sounded, how they ought to be pronounced, and that made me uneasy about opening my mouth. My place in the family that year was to watch, which was how I was learning to listen. Id sit at the kitchen tablewhere most stories of any importance were toldand read lips, piecing together the shapes they formed until they made a kind of sense. Lip readingwhether you know youre doing it or notis a hard, intimate business, and during my ninth year, when the way people sucked or licked their teeth as they were talking took sneaking precedence over the look in their eyes, all that rapt staring at mouths would wring me dry. After every couple of stories, Id turn my gaze away, give myself a breather, and recharge. It took me so much concentrated effort to make sense, much less sentences, out of the lips as they moved, that any and every utterance had to have a payoff. If people were making idle conversation or empty yak about, say, grocery shopping or getting their nails done, Id heave the sigh of the doomed and lean my head against the table, pressing the bridge of my nose against the metal rim hard enough to dig a furrow. Id glance up every now and then to see if the topic had changed to something more interesting, like who had died and what had killed them. If talk was stalled at yellow versus white onions or the rising price of a pedicure, Id get to pitying myself, slaving like a dung beetle over a worthless bit of nothing, and give upput my head back down on the table, close my eyes, and deliberately lose control. The rising, falling mumble of those incomprehensible voices would wash over me until sounds would inexplicably leap from the muttering to shake themselves clear in my mind as words. A name, the time of night, the make of a car, a part of town, a tired old clich. Id string them together as randomly as I caught them, but they still always seemed to be telling me a story. Ruby, two a.m., Ford, east of Hutto, dying of hunger, and Id see the black-eyed Great-Aunt Ruby Id never met gunning her Mustang down the one main street of a hick Texas town en route to love or a Burger King. It soothed my hurt and anger to imagine all those arbitrary words telling me the illicit secrets behind everything I hadnt heard.

Which may be why I now find myself enamored of the memoir. The good ones thrill me every bit as much as the great novels, but its the crappy ones Ive lost my heart to. They make me feel like a rescue dog, sniffing out the dim glimmerings of feelings sincere and raw within a tangled wreckage of inchoate ramblings and obvious lies. Ive been reading a ton of bad ones lately, most of which Ive gotten only halfway through. They are piled up by my bedside and not in the best of shape. Im a passionate reader and the books have suffered for it, their covers wavy from having been dropped in the tub, spines busted from being tossed on the floor, pages folded, creased, coffee-stained, and marked with ink. Red. I feel intensely fond of the whole lot of lousy writing that has found its way to print because I smell in those stinkers a fecund democracy. Every sort of half-coherent loser getting their say. Maybe even mean little deaf queers like me.

As a toddler I was an ardent chatterbox, with such an adult and rapid-fire vocabulary that one of our German neighbors in Stuttgart mistook me for a dwarf. By age seven I was becoming what passes in our family of energetic talkers as taciturn, more like my father, who would sneak away from the kitchen table in the middle of a detailed piece of family gossip my mother and my sister, Trudy, were sharing and flee to the bathroom so he could read the Sunday paper in peace. I never left the table. I just stopped talking. My mother and Trudy never worried about my growing silencetheyd taken it as appreciative. But then they didnt know the reasons behind it. Sounds had started disappearing all around me. I didnt know where to, and I didnt think to asknot then and not the handful of years later when I started having my visions. Or so I liked to call them, although they never clued me in to anything useful or remotely prophetic.

Whatever they were, they were first visited upon me when I was nine and our family had resettled from Berlin, Germany, to Fort Hood, Texas. One hot spring Texas night I was sprawled on the dry grass of our new front yard, gazing up at a spiral of stars, when I suddenly found myself six feet in the air, looking down at myself lying on the grass looking up at those stars. I was a little pissed off by how perfectly cheerful my body seemed without me.

These odd displacements werent exactly a daily occurrence, but that year, they happened often enough to make themselves familiar. Once I went zooming to the ceiling of the school gym as if sucked up by a vacuum. I dangled there looking down on a scene that was small as a dollhouse, everything normal about it. My PE teacher blew herself red on her whistle while my six classmates and I, all of us looking a bit zaftig in our blue shorts and white snap blouses, thundered across the polished wooden floor. No one else seemed aware that while my body was stampeding along with the rest of the herd, I wasnt there at all. Id become a much more delicate presence adrift in the rafters, smiling down on our sweaty race as if it were a mildly amusing bit of low comedy. Decades later in London, where Id gone to perform one of my one-woman shows, I saw something of the same kind of life in miniature in a penny-mechanical shop. A carved wooden man, not much bigger than my own thumb, was sleeping on a perfectly detailed cloth and wooden bed inside his tiny bedroom. He slept there until I dropped in a coin that clicked the switch that set it all in motion. With a ticking noise, the window of his minuscule room flew open and a dream horse, its nostrils and eyes painted to look as wild and flaring as its mane, poked its head through the gap. Up the little man sat, his closed doll eyes snapping wide with alarm as the horse reared and the wooden chair at the foot of the bed tilted and twirled. Watching that nightmare unfold in the little mans shoebox of a room awakened in me the same queasy prickle of enchantment Id felt as a kid, looking down on a play-pretend world.

During that ninth year of my childhood, in my own bed at night, Id hear a babbling in my head, a deep hoarse muttering that almost made sense and filled me with such terror and yearning that, if Id been at all religious, I might have thought it was the voice of God grumbling at me. Even after my visions and voices were exposed for what they were, they still had that power to pin me shivering to my bed. Fearful as they could be, I loved them and held them in awe, believing them to be glimpses of a secret from the beyond that had chosen to reveal itself only to me, special me.

Youd think Id have told someone about all these sinister and miraculous goings-on. And once I did. The day after Id zipped up to the rafters, I told my baby sister, Tenley, that I could leave my body and fly. She was only four at the time but perfectly capable of raising a skeptical eyebrow and suggesting I jump off the top of our carport to prove it. I figured the leap might trick my body into taking flight before it could slam to the ground, so I took the gamble, went barreling off the gravel roof, arms spread like Superboy, and dropped like Wile E. Coyote tied to an anvil. When I hiked myself to my knees, the scorn in Tenleys eyes made me feel silly as hell. For the rest of that year, until they turned menacing, I kept the existence of my visions strictly to myself. I took to thinking of them as fragile wonders, like the locked, forgotten garden in my favorite book. If I didnt keep them private, shield them from idle prying, ridicule, or disbelief, theyd wither into dust, the same way my own secret heart would wither if I ever admitted aloud the longing for other little girls that was growing there.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir»

Look at similar books to Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mean Little deaf Queer: A Memoir and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.