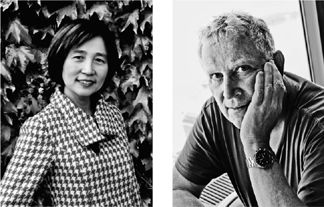

EMILY WU & LARRY ENGELMANN

Feather in the Storm

Emily Wus stories have appeared in both Chinese and American publications. She is one of the featured subjects in the film Up to the Mountain, Down to the Village. She lives with her two children in Cupertino, California.

Larry Engelmann is the author of five previous books, including Daughter of China. His writing has appeared in many publications, including American Heritage, Smithsonian, and the magazines of both the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post. He lives in San Jose, California.

ALSO BY LARRY ENGELMANN

Intemperance

The Goddess and the American Girl

Tears Before the Rain

Daughter of China

They Said That

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, JANUARY 2008

Copyright 2006 by Emily Wu and Larry Engelmann

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2006.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows:

Wu, Emily.

Feather in the storm: a childhood lost in chaos / Emily Wu and Larry Engelmann.

p. cm.

1. ChinaHistoryCultural Revolution, 19661976Personal narratives.

I. Engelmann, Larry. II. Title

DS778.7.W723 2006

951.225dc22 2006041772

[B]

eISBN: 978-0-307-48472-7

Photograph of Emily Wu Anchee Min

Photograph of Larry Engelmann Jane Ling

www.anchorbooks.com

v3.1

For my beloved children

Jasmine and Erik

and for the children lost in the Chaos

and those who loved them

Contents

Weve lived in a time of chaos, when it is impossible to love.

MAO ZEDONG (18931976)

Authors Note

That was a long time ago, but its wrong what they say about the past, Ive learned, about how you can bury it. Because the past claws its way out.

KHALED HOSSEINI, The Kite Runner (2003)

Feather in the Storm is my story and the story of my family. It is also the story of millions of children like me whose stories have never been told. We had the misfortune to be born and raised in a time of revolutionary upheaval, brutality, and inhumanity. Only recently, after returning to China several times to visit the towns and villages where I was raised, and interviewing my aunts and uncles and my dearest childhood friend, Qin Xiaolan, was I able to write about those times.

The conversations recorded here from my youth may be qualified with the phrase to the best of our memory when the conversation involved more than one individual. Certain events, such as the visit to my father, were retold to me by both my mother and father and the precise words and facts were theirs. Their personal memories informed my own memory. Some conversations, such as those with the Sun children, I can still clearly hear in my mind, as they pounded on the school door and threatened me, and I remember the sound of their feet as they pursued me. As I grew older and attended school, made home visits, lived in the countryside, and formed close friendships, I did not have to go back as far to remember what was said, how it was said, and what my reaction and response was.

This is, therefore, a work of nonfiction, though some names have been changed to protect the identity of an individual or a family. I researched with others the events described here. I went back to the places where I had lived. I read and reread lengthy diaries and journals I had kept. I talked to my old friends and detractors who still lived in China. I opened doors to rooms I had not entered in decades. I went inside. I sat, thought and remembered. I heard again the voices I heard there when I was a girl. I heard the laughter and the cries. I remembered the things I describeevents, people, places, sounds and smells. Like anyone recalling distant events in faraway places, my memories are personal, and the words I remember may vary from what someone else remembers. But like everyone who passes through a long, traumatic series of events, I remember those events more accurately than if my childhood days had been uneventful. This is what I still see and hear when I close my eyes and those times descend on me again.

Over the years I have come to believe in the basic goodness of people and the fundamental dignity and strength of humanity. But there was a time in my life when such a belief was impossible. Ironically, that was when I was most vulnerable, most innocent, and most in need of compassion. Those were the years of my childhooda childhood that was lost too soon.

I survived the years of revolutionary chaos in China. Millions did not. Many of those who did not survive were children. And many of those children were my friends. We were all innocent and often unseen victims of a dark and indecent time.

It is my hope that this memoir may serve as a reminder and a memorial to all of the children who were lost in the Chaos and to all of those who, even though they survived, were robbed of their birthrightinnocence and happiness. Perhaps in telling my story, I can help assure that other children will never be forced to relive it.

Emily Wu

Cupertino, California

PROLOGUE

Visitors

When I was a small boy, my grandmother told me about a distant uncle who was living in China during the Cultural Revolution. He promised to send a picture of himself to his relatives in America. If conditions were good, he said, he would be standing. If they were bad, he would be sitting. In the photo he sent us, my grandmother whispered, he was lying down.

DAVID HENRY HWANG (1997)

The concentration camp is six miles from the train station. There is no public transportation. Visitors must walk to the camp. The woman carrying me shifts me to her side, asks if Im comfortable, and sets out on the last leg of our journey. She stops to rest. There are no benches, no trees, no grass, not even weeds. All around us is a dull, parched, lifeless landscape under a withering and unforgiving sun. It is Saturday, June 3, 1961. My third birthday. I am on my way to meet my father for the first time.

We pass several places not far from the road where the earth is ruffled with rows of low mounds. A wooden stake with a number scratched on it protrudes from each mound. These are graves of the prisonersmen, women and children. The government does not want prisoners to waste time burying the dead. Relatives are summoned to dig the graves and to collect the belongings of the deceased. People pass us. They are like shadows carrying shovels and small sacks, moving slowly to and from the camp. They glance up with sad, hollow eyes.

After an hour we are only halfway to the camp. The woman stops and puts me down. She looks into the distance and wonders if she can make it before the brief visiting period is over.

An old man approaches on a horse-drawn cart. He wears drab rags and a frayed cap. His skin is dark and leathery from the sun. Hes toothless, and his face is shrunken and small. The cart is piled high with straw. The horse is skin and bones and moves as if each step is its last. The woman moves to the middle of the road and waves for the man to stop. He draws back on the reins, pauses and looks at us impatiently but says nothing.