Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For my mother, in gratitude for her dark mind and warm heart

it is finally as though that thing of monstrous interest

were happening in the sky

but the sun is setting and prevents you from seeing it

John Ashbery

ALL CRIME ALL THE TIME

Until a few years ago, Oxygen was a cable TV channel that targeted a young, female demographic with forgettable high-drama shows with names like Last Squad Standing and Bad Girls Club . According to network executives, the millennial women they were hoping to capture craved freshness and authenticity, high emotional stakes and optimism. It didnt take long for the executives to figure out that what young women actually wanted was more shows about murder. When the struggling network began airing a dedicated true crime block in 2015, viewership increased by 42 percent. In 2017, the network rebranded and adopted revised programming priorities: all crime, all the time.

Viewership skyrocketed; Oxygen had tapped into something big. For the past few years, as the US murder rate has approached historic lows, stories about murder have become culturally ascendant. The crime minded among us were inundated with content, whether our tastes tended toward high-end HBO documentaries interrogating the justice system or something more like Investigation Discoverys Swamp Murders . (Or, as was often the case, both. True crime tends to scramble traditional high/low categorizations.) Shops popped up on Etsy selling enamel pins of Ted Bundys Volkswagen Beetle and iPhone cases depicting Jeffrey Dahmers face. There were approximately a million new podcasts, and they all had something to investigate .

In 2018, Oxygen hosted its second annual fan conventionCrimeConin Nashvilles Marriott Opryland hotel. The Opryland, as I was proudly told at check-in, was the second-biggest noncasino hotel in the world. You know that American tendency to equate bigness with luxury and plenitude with worth? The Opryland was that, in hotel form. There was lush indoor landscaping and fountains that erupted in elaborately choreographed spurts and infinite snack options you could charge to your room. You could eat a dinner at a steakhouse housed inside a replica of an antebellum mansion. For $10, you could ride a boat down the quarter-mile-long river that flowed through one of the hotels atriums; the water, I was told, included a drop from every river in the world.

The week before CrimeCon, the Opryland had welcomed a group of cement salespeople, and the week after it would host a convention of international-supply-chain managers, but for these three days in May, it was full of young women wearing T-shirts that said things like BASICALLY A DETECTIVE and DNA OR IT DIDNT HAPPEN and IM JUST HERE TO ESTABLISH AN ALIBI .

On day one of CrimeCon, I found a seat in the ballroom among a couple of thousand women and a smattering of men. The sound system blasted cheery pop music as the screens flanking the stage scrolled through a slideshow of crime-related imagesmug shots and yellow police tape and close-ups of alarming, contextless headlines: Man Accused of Stabbing Mother, Deadly Stabbing Suspect Arrested, Four People Shot.

Oxygen shows feature a stable of authoritative crime experts, mostly men with handsome-haggard faces and law enforcement experience. Theyre real people, but they always seem half in character, as if they were playing a beloved but slightly remote and overprotective father on a network drama. There seemed to be at least one of them on every true crime show, these inexplicably sexy cop-dads. One of them, former FBI profiler Jim Clemente, wearing a cowboy hat, strolled out onto the stage to a round of huge cheers. CrimeCon had officially begun.

Crimes are driven by the why , the motive, Clemente said. We need that why to solve most crimes. Because the how and the why gives you the who . We also use motives in daily life. Why eat a sandwich? Because youre hungry. But with crime, sometimes the motives are hidden. Why did she run away? Was it to escape coercive control? Why did he kill her? Was it jealousy? Or was it something more insidious?

And why are you here? Do you love the genre? Do you want to solve a cold case? Clementes voice slowed and deepened; he was transitioning into serious mode. Or you know or knew someone who got murdered? Or you yourself were a victim of a crime? I have a theory. You want to learn so you can protect those you love. Its a very altruistic goal. His voice changed againI had a feeling these tonal shifts would get exhausting over the long weekend. Have fun, he bellowed. And remember: hashtag CrimeCon on your posts!

* * *

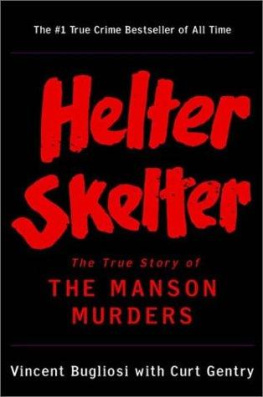

I should have felt at home at CrimeCon. For most of my postadolescent life, Ive periodically sunk into what Ive come to think of as a crime funk. I was the kind of gloomy child who filched her mothers People magazines to read not about the celebrities, but about the killers and kidnappers and suspicious overdoses. As I got older, my appetite for murder stories seemed to depend on how much turbulence was in my own life. The more sad or lost or angry I felt, the more I craved crime. I was a teenager storming with hormones when I pulled Helter Skelter off my parents shelf and gave myself Manson Family nightmares, and a little older and a lot more depressed when I set out to read every single Manson Girl memoir. When I learned that the Columbine killers journals were online, I read those, too.

In my crime funks, the perspectives I identified with shifted depending on what else was going on in my life. Sometimes I saw myself in the detective, the only one smart enough to put the pieces together; sometimes in the innocent victim, at the mercy of sinister forces much bigger than me; sometimes in the crusading defender, righting the wrongs of a flawed and corrupt system; sometimes, even, I saw myself in the killer.

* * *

That the true crime obsessives packing the hallways at CrimeCon were almost all women was, on its surface, perplexing. The vast majority of violent crimes are committed by men. Most murder victims are also male. Homicide detectives and criminal investigators: predominantly male. Attorneys in criminal cases are mostly men. Put simply, the world of violent crime is masculine, at least statistically.

But the consumers of crime stories are decidedly female. Women make up the majority of the readers of true crime books and the listeners of true crime podcasts. Television executives and writers, forensic scientists and activists and exonerees all agree: true crime is a genre that overwhelmingly appeals to women.

Women arent just passively consuming these stories; theyre also participating in them. Start reading through one of the many online sleuthing forums where amateurs speculate about unsolved crimesand sometimes solve themand youll find that most of the posters are women. More than seven in ten students of forensic science, one of the fastest-growing college majors, are women. A few years ago, two undergraduates at the University of Pittsburgh founded a Cold Case Club so they could spend their extracurricular hours investigating murders; the group is, unsurprisingly, dominated by women.

Sometimes womens attraction to true crime is dismissed as trashy and voyeuristic (because women are vapid!). Sometimes it is unquestioningly celebrated as feminist (because if women like something, then it must be feminist!). And some argue that women read about serial killers to avoid becoming victims. This is the most flattering theoryand also, it seemed to me, the most incomplete. By presuming that womens dark thoughts were merely pragmatic, those thoughts are drained of their menace. True crime wasnt something we women at CrimeCon were consuming begrudgingly, for our own good. We found pleasure in these bleak accounts of kidnappings and assaults and torture chambers, and you could tell by how often we fell back on the language of appetite, of bingeing, of obsession. A different, more alarming hypothesis was the one I tended to prefer: perhaps we liked creepy stories because something creepy was in us.

Next page