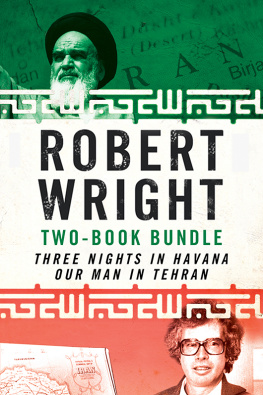

Other Press edition 2011

Copyright 2010 by Robert Wright

First published in Canada in 2010 by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Design revisions for this edition by Simon M. Sullivan

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the following for permission to reproduce photographs:

Ken Taylor, pp. (passport).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Wright, Robert A. (Robert Anthony), 1960

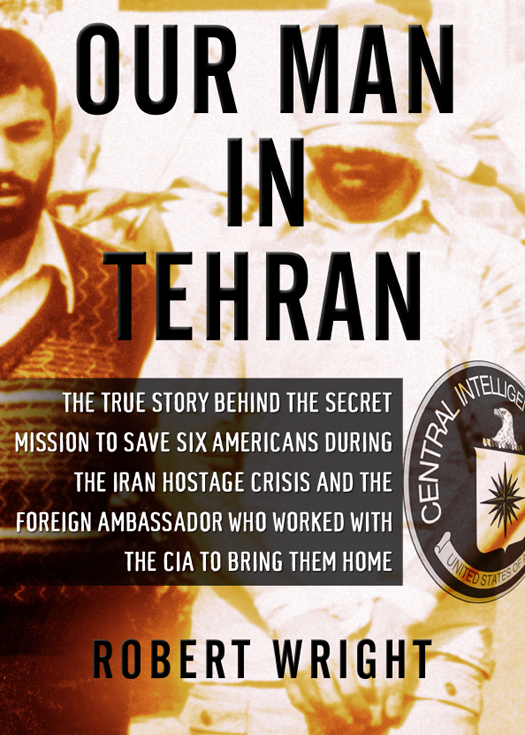

Our man in Tehran : the true story behind the secret mission to save six Americans during the Iran Hostage Crisis and the foreign ambassador who worked with the CIA to bring them home / by Robert Wright.Other Press ed.

p. cm.

First published in Canada in 2010 by HarperCollins Publishers LtdT.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-414-6 1. Iran Hostage Crisis, 1979-1981. 2. Taylor, Kenneth, 1934- 3. DiplomatsUnited States. 4. EscapesIran. 5. Diplomatic and consular service, CanadianIran. 6. Diplomatic and consular service, AmericanIran. 7. United StatesForeign relationsIran. 8. IranForeign relationsUnited States. 9. AmbassadorsCanadaBiography. I. Title.

E183.8.I55W75 2011

955.054dc22 2010020376

v3.1

For Laura, Helena, Anna and Michael

An ambassador is a man of virtue sent abroad to lie for his country.

Henry Wotton, Sr. (15681639)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

O ur Man in Tehran recounts the exploits of Canadas fifth ambassador to Iran, Kenneth D. Taylor, the man who, in January 1980, became the worlds most celebrated diplomat for his role in rescuing six Americans during the Iran hostage crisis.

I first met Ken Taylor in March 2008, in the restaurant of Torontos Park Hyatt hotel. We had agreed to conduct our first interview for this book over breakfast and, in typical fashion, Taylor was punctual, impeccably dressed and full of energy despite having underslept. While we were getting acquainted, sipping coffee and chatting casually about current affairs, a man in his mid-forties approached our table and asked politely if he could interrupt our conversation. He identified himself as an American businessman. He was dining with an older Canadian colleague, he said, who had pointed Taylor out to him and reminded him of the role he had played in rescuing the American diplomats from Tehran. I am no groupie, the man told Taylor, but I just wanted to say thanks. Taylor shook the mans hand warmly, without so much as a hint that this scene had played out hundreds of times over the last three decades.

There is a mystique about Ken Taylor even now. Yet, like the so-called Canadian caper itself, our sense of the man remains one-dimensional, almost a caricature. When the Central Intelligence Agency allowed some of its covert operatives to step out of the shadows in 1997 and take credit for rescuing the six Americans from Tehran, it was easy to believe that the affable ambassador had exaggerated his, and by extension Canadas, contribution. Some Canadians, in the press and even in government, turned on him, branding him an impostor. Others were quietly disillusioned. In spite of Taylors once-ubiquitous presence in North American popular culture, we suddenly realized that he had told us almost nothing about what had actually happened in Tehran. As it turns out, Ambassador Taylor was a master of the black art magicians call legerdemain, or misdirection. For the whole time he was cultivating his public persona as the unassuming hero of Tehran, he was concealing more about what he had actually done there than most of us could have imagined. In piecing together this story for the first time, Our Man in Tehran shines a light on the real Ken Taylor, a man we never really knew.

I first met former secretary of state for external affairs Flora MacDonald several weeks after my introduction to Ken Taylor. She graciously agreed to an interview at her home, a cozy Ottawa apartment that overlooks the Rideau Canal, where she still ice-skates regularly. Her place is filled with the trophies of a life spent in Canadian and international politicsgifts from former heads of state, honorary degrees, various paintings, sculptures and tapestries from around the world. Among Ms. MacDonalds many mementoes is a small, framed watercolor. It shows two Muslim women in full chador (veil and gown) walking down a city sidewalk, small trees in the foreground and mountains rising in the background. The painting is obviously the work of an amateur, out of place among MacDonalds museum-quality treasures. I asked her about it. She told me that the watercolor was painted by American charg daffaires Bruce Laingen during his 444 days of captivity in Iran. This streetscape, she explained, had been his only window on the world for the fifteen months he was imprisoned at the Iranian foreign ministry. Laingen had given MacDonald the painting as a token of his gratitude for her decisive role in rescuing his six American colleagues.

This vignette speaks to the broader pattern I encountered at every stage of my research, of enduring personal attachments forged in cruel circumstances. Ken Taylor and Bruce Laingen have remained good friends since their time in Tehran together, as have retired Canadian diplomat Roger Lucy and two of the Americans he helped to rescue, Mark and Cora Lijek. Flora MacDonalds collaboration with U.S. secretary of state Cyrus Vance cemented a close personal bond that lasted until his death in 2002. Many of the politicians, bureaucrats, diplomats and intelligence officers connected with the hostage crisis express identical sentimentsa profound sense of camaraderie coupled with a deep reservoir of pride in what they accomplished together.

A word on sources. Like many Canadian historians, I have benefited greatly from federal access-to-information and privacy (ATIP) provisions that allow for the opening (declassifying) of archival documents upon request. Our Man in Tehran is largely based on hundreds of newly opened External Affairs cables that moved between Ottawa, Washington, Tehran and other world capitals in the period before, during and after the hostage crisis. Because these cables were written in diplomatic languageterse, declarative sentences, all in capital letters and without articles (the, an)I have reformed them slightly for ease of reading. Articles have been inserted into cable excerpts without the use of square brackets. Thus, MUCH OF PUBLIC REACTION HAS FOCUSED ON SPONSOR OF RESOLUTION becomes Much of the public reaction has focused on the sponsor of the resolution. I have also ignored the diplomatic convention of repeating the word not. Thus, EMBASSY HAS NOT/NOT BEEN AFFECTED becomes The embassy has not been affected. In every other respect, the sources cited in the endnotes conform to established scholarly standards. There is no invented dialogue in this book.

Our Man in Tehran could not have been written without the help of others. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge them here.