Contents

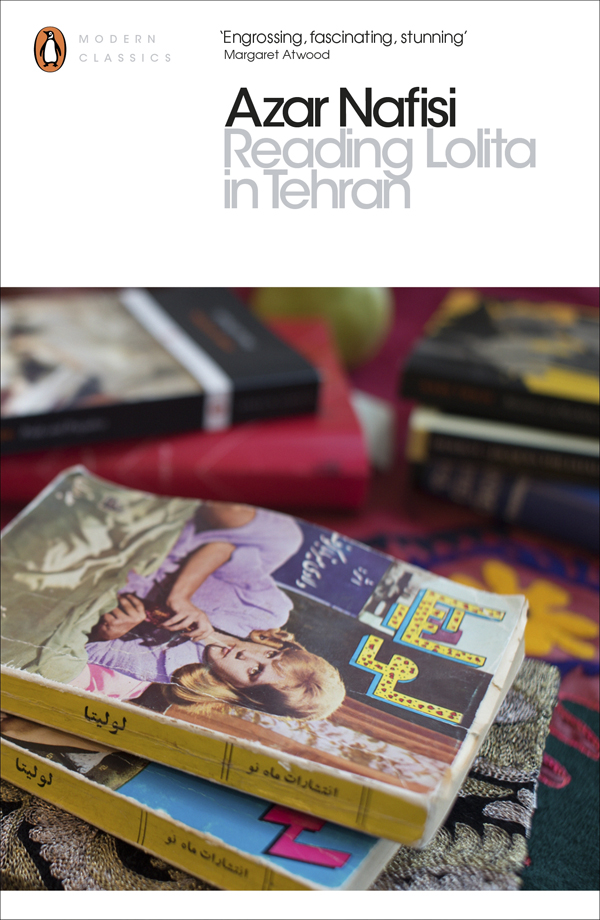

Azar Nafisi

READING LOLITA IN TEHRAN

A Memoir in Books

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in the United States of America by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. 2003

This edition published in Penguin Classics 2015

Copyright Azar Nafisi, 2003

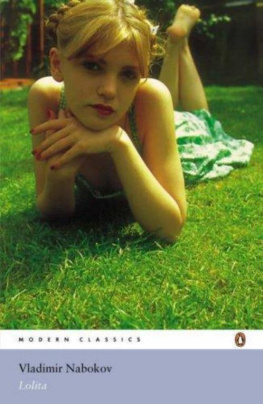

Cover S. J. Staniski

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Estate of Vladimir Nabokov: Extracts from the correspondence of Vra Nabokov. All rights reserved. Reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Vladimir Nabokov.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company and Faber and Faber, Limited: Excerpt from Burnt Norton in FOUR QUARTETS by T. S. Eliot, published in the United Kingdom as part of COLLECTED POEMS 19091962, copyright 1936 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, and copyright renewed 1964 by T. S. Eliot. Rights throughout the United Kingdom are controlled by Faber and Faber, Limited. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company and Faber and Faber, Limited.

Liveright Publishing Corporation: somewhere I have never travelled, gladly beyond, from COMPLETE POEMS: 19041962 by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage, copyright 1931, 1959, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust, copyright 1979 by George James Firmage.

Reprinted by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Random House, Inc.: Seven lines from Letter to Lord Byron from W. H. AUDEN: THE COLLECTED POEMS by W. H. Auden, copyright 1937 by W. H. Auden. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

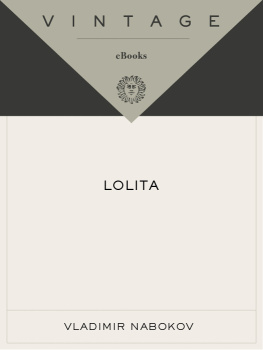

Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc.: Excerpts from LOLITA, by Vladimir Nabokov, copyright 1955 by Vladimir Nabokov. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-141-98261-8

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Azar Nafisi is a visiting professor and the director of the Dialogue Project at the Foreign Policy Institute of Johns Hopkins University. She has taught Western literature at the University of Tehran, the Free Islamic University and the University of Allameh Tabatabai in Iran. In 1981 she was expelled from the University of Tehran after refusing to wear the veil. In 1994 she won a teaching fellowship from Oxford University, and in 1997 she and her family left Iran for America. She has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and The New Republic and has appeared on countless radio and television programs. She lives in Washington, D.C., with her husband and two children.

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

IN MEMORY OF MY MOTHER, NEZHAT NAFISI

FOR MY FATHER, AHMAD NAFISI,

AND MY FAMILY: BIJAN, NEGAR AND DARA NADERI

To whom do we tell what happened on the Earth, for whom do we place everywhere huge Mirrors in the hope that they will be filled up And will stay so?

Czeslaw Milosz, Annalena

Authors Note

Aspects of characters and events in this story have been changed mainly to protect individuals, not just from the eye of the censor but also from those who read such narratives to discover whos who and who did what to whom, thriving on and filling their own emptiness through oth ers secrets. The facts in this story are true insofar as any memory is ever truthful, but I have made every effort to protect friends and students, baptizing them with new names and disguising them perhaps even from themselves, changing and interchanging facets of their lives so that their secrets are safe.

Part I

LOLITA

1

In the fall of 1995, after resigning from my last academic post, I decided to indulge myself and fulfill a dream. I chose seven of my best and most committed students and invited them to come to my home every Thursday morning to discuss literature. They were all womento teach a mixed class in the privacy of my home was too risky, even if we were discussing harmless works of fiction. One persistent male student, although barred from our class, insisted on his rights. So he, Nima, read the assigned material, and on special days he would come to my house to talk about the books we were reading.

I often teasingly reminded my students of Muriel Sparks The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and asked, Which one of you will finally betray me? For I am a pessimist by nature and I was sure at least one would turn against me. Nassrin once responded mischievously, You yourself told us that in the final analysis we are our own betrayers, playing Judas to our own Christ. Manna pointed out that I was no Miss Brodie, and they, well, they were what they were. She reminded me of a warning I was fond of repeating: do not, under any circumstances, belittle a work of fiction by trying to turn it into a carbon copy of real life; what we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth. Yet I suppose that if I were to go against my own recommendation and choose a work of fiction that would most resonate with our lives in the Islamic Republic of Iran, it would not be The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie or even 1984 but perhaps Nabokovs Invitation to a Beheading or better yet, Lolita.

A couple of years after we had begun our Thursday-morning seminars, on the last night I was in Tehran, a few friends and students came to say good-bye and to help me pack. When we had deprived the house of all its items, when the objects had vanished and the colors had faded into eight gray suitcases, like errant genies evaporating into their bottles, my students and I stood against the bare white wall of the dining room and took two photographs.

I have the two photographs in front of me now. In the first there are seven women, standing against a white wall. They are, according to the law of the land, dressed in black robes and head scarves, covered except for the oval of their faces and their hands. In the second photograph the same group, in the same position, stands against the same wall. Only they have taken off their coverings. Splashes of color separate one from the next. Each has become distinct through the color and style of her clothes, the color and the length of her hair; not even the two who are still wearing their head scarves look the same.