Create dangerously, for people who read dangerously. This is what Ive always thought it meant to be a writer. Writing, knowing in part that no matter how trivial your words may seem, someday, somewhere, someone may risk his or her life to read them.

When a reader falls in love with a book, it leaves its essence inside him, like radioactive fallout in an arable field, and after that there are certain crops that will no longer grow in him, while other, stranger, more fantastic growths may occasionally be produced.

Salman Rushdie

ON OCTOBER 8, 2016, I sat down and wrote a letter to my father, who had been dead for twelve years. I know the date because I noted in my letter that it was the day after the Washington Post published the lewd conversation between Billy Bush and Donald Trump in which Trump boasted about grabbing womens genitals.

During his lifetime, it was not unusual for me to exchange letters with my father. He first wrote me when I was four, in a diary addressed only to me, which, after his death, I discovered among his letters and diaries. I first wrote to him when I was six, while he was in America studying. I jotted down a few words on scraps of paper torn from my notebook, addressing him as Baba jan, the equivalent of dearest Dad in Persian, and signing off the letter with Babas daughter. We wrote not just when one of us was traveling, but also while we lived in the same countryeven when we lived in the same house.

We wrote each other long letters on important occasions: when I was sent to England at the age of thirteen to continue my studies, or when my father, then the mayor of Tehran, was jailed for political reasons in 1963because he would not obey his archenemies, the prime minister and the minister of the interior. We exchanged letters when he was finally exonerated of all charges, after having spent four years in what was called a temporary jail. We exchanged letters about my first wedding, at the age of eighteen, which he, being in jail, could not attend, and I continued to write from the University of Oklahoma, which I attended along with my first husband. My father was the first person I wrote to about my unhappy marriage and the decision to divorce, and, a few years later, about my second husband, Bijan, and my decision to marry him.

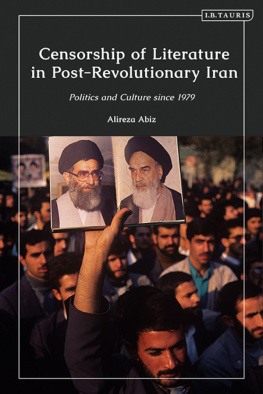

I graduated college and continued on for a PhD, which I completed right after the Islamic Revolution in 1979. I returned to Iran to teach but was expelled from the university for refusing to wear the mandatory veil. My father and I wrote about all of this, of course. We wrote when my daughter, Negar, and my son, Dara, were born. When I migrated back to America in July 1997, we exchanged long faxes in which we discussed everything from the most personal to the political and the intellectual: how lucky it was that my husband and I and our children lived in Washington, DC, the same city where some of my closest friends, and my kind and generous sisters-in-law, lived with their families; how exhilarating it was to watch uncensored movies and read uncensored books; how much I missed him. We wrote about the excitement of my new work, the books we each read, the lessons to be learned from Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Montaigne. He created a list of the great works of Iranian literature for me to pass down to my children so that they will remember Iran, he said. We discussed the books I taught in my classes, as well as Americas evasion of reality and its growing obsession with comfort and entertainment. I wrote to him when I was happy, I wrote to him when I was unhappy, I wrote to him when I was excited, I wrote to him when I was angry or depressed.

On that day in October, I wrote because I was depressed, thinking of the two countries I called home. In Iran, the theocracy was in full force; despite peoples intense dissatisfaction and consistent protests, nothing had changed. The ayatollahs continued to harass, jail, torture, and kill innocent citizens. In America, although vastly different from Iran, the society was fast becoming polarizedtoo much ideology and not enough discoursein some instances reminding me of the Islamic Republic. My father and I had many exchanges about how to deal with our oppressors, with those we call not just adversary but enemy. His imprisonment and those responsible for it were the topic of many conversations over the years, and, later, a revolution and a war made it almost a daily preoccupation.

And now, in America, I returned to the same question, finding it so central to the preservation of democracy. I wrote my father that I felt tongue-tied thinking of Trumps candidacy, not just because of his person but also because of what he represented and revealed about us. I wrote him that in the Trump era we are preoccupied by our enemies, real or manufactured, that most of our actions are reactions to these real or fabricated enemies. I also told father that I missed him: As we say in Persian, your place is empty. His place had never been this empty.

I wrote how, all my life, I felt I had been his number one defender, confidante, friend, and fellow conspirator, despite our times of anger, or feelings of betrayal and bitterness. I said, At times, I was hard on you, in the same hard way I loved you. But now death and distance have brought out the other feelings, the ones I evoke when I return to the happiest moments of my childhood: the storytelling.

Like all loving and intimate relationships, ours had its ups and downs, but there was one aspect of our bond that remained unsullied: the stories he told me each night during my childhood. When my father would sit down to tell me some of my favorite stories, the unexpected joy was like a brief electric shock. I knew instinctively, even when I was very young, that the moment was sacred, I was being offered something precious and rare: the key to a secret world.

He was democratic in choosing the stories. One night he would tell the tales from our epic poet Ferdowsis book Shahnameh (The Book of Kings); the next night, we would travel to France with the Little Prince; the night after that, to England with Alice. Then to Denmark with the Little Match Girl, to Turkey with Mullah Nassreddin, to America with Charlotte and her web, or to Italy with Pinocchio. He brought the whole world into my little room. Time and again as a teenager, and later as a college student, a teacher, a writer, an activist, a mother, I would return to that room to draw upon the strength of those stories.

I left Iran for the first time at the age of thirteen to continue my education in England, and, ever since, books and stories have been my talismans, my portable home, the only home I could rely on, the only home I knew would never betray me, the only home I could never be forced to leave. Reading and writing have protected me through the worst moments of my life, through loneliness, terror, doubt, and anxiety. And they have also given me new eyes with which to see both my homeland and my adopted country.

In Iran, like all totalitarian states, the regime pays too much attention to poets and writers, harassing, jailing, and even killing them. The problem in America is that too little attention is paid to them. They are silenced not by torture and jail but by indifference and negligence. I am reminded of James Baldwins claim that Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind. In the United States, it is mainly we, the people, who are the problem; we who take the existence of challenging literature for granted, or see reading as solely a comfort, seeking out only texts that confirm our presuppositions and prejudices. Perhaps for us, the very idea of change is dangerous, and what we avoid is reading dangerously.