"You know me, Thomas," she said playfully, "if you will only think You may have one guess more." My whole body felt thick and heavy. I could only shake my head, and the horse's bridle rang, silver echoing the singing in my ears. "True Thomas, riddle me this: what is it you sing of nightly and rhyme daily? True love, heroism, glory, sorrow, enchantment...."

But all my rhymes were gone.

She added, "No woman of Earth, nor yet of Heaven."

Her face blurred before me: all the women I had ever had were there in it, all my moments of ecstasy and fulfillmentand they seemed dry next to her promised fulfillment, stale next to her excitement, sad next to her pleasure.

"I am the Queen of Elfland, Thomas."

I pulled her to my mouth, and tasted fruit and flesh undreamed of. She quenched my thirst, and at the same time filled me with hunger I knew would never leave me. For just one moment my mind cleared as I thought, I am lost

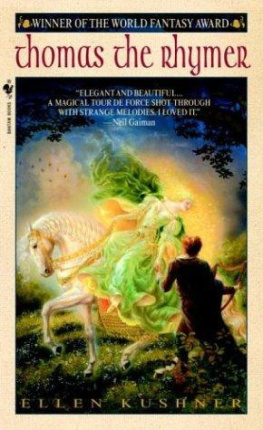

ELLEN KUSHNER

Thomas the Rhymer

VGSF

VGSF is an imprint of Victor Gollancz Ltd 14 Henrietta Street, London WC2E 8QJ

First published in Great Britain 1991 by Victor Gollancz Ltd

First VGSF edition 1992

Copyright 1990 by Ellen Kushner

The right of Ellen Kushner to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 575 05174 4

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

TO THE ONES WHO HAVE GONE BEFORE:

Sir Walter Scott

Belle and Hyman Lupeson

Rose and Boris Kushner

Joy Chute

and the Jews of York, c.e . 1190

PART I

Gavin

Jack Orion was as good a fiddler

As ever fiddled on a string

He could make young women mad

With the tunes his fiddle could sing:

He could fiddle salt from the salt water

Or marble from a marble stone

Or the milk out of a maiden's breast

Though babies she'd got none.

Trad, and A. L. Lloyd (from Child ballad no. 67, "Glasgerion")

Im not a teller of tales, not like the Rhymer. My voice isn't smooth, nor my tongue quick. I know a few tunes, everyone does, but nothing like his: from me you'll never hear songs of gentle maidens fording seven rivers for their false lover so bittersweet as to make the hardest old soldiers weep; nor yet merry ones of rich misers tricked out of their gold, with the twist of a word and a jest so neatly turned that the meanest old uncle that ever pinched a dowry still laughs without offense. Well, if s a power, surely, that music and those words, and I just haven't got it.

Not that I'm sure I'd take it, even if it were offered me. One of Tom's very tales is of Jock of the Knowe, that was coming home from Mellerstain Fair with a long face, for he'd walked all that way with his old shorthorned cow to sell at the fair, but not a man would have her. So here's Jock returning to his goodwife with no money nor goods, and winter coming on. Jock's going on down Mellerstain road with his cow, and he starts in railing at her, in a temper, like: "What wouldn't I give to be quit of you, and good money in my purse?"

Well, just then he sees a cloaked man by the side of the road. And the man says, "Good even to you, Jock of the Knowe. And how's the milk from your shorthorned cow?"

Taking the stranger for some man from the fair, Jock answers, "Why, this cow gives half cream and half honey. And if she gives one bucket at morning, she gives two at evening."

They fall to bargaining over the price of the cow. It seems to Jock that anyone wandering the roads after the fair in search of a cow must be in a hard case, so he's setting the price high. Then the tall stranger says, "Well, silver is silver, but I can offer you something worth twice that, cow and all." And he pulls out a fiddle.

Jock says he can't even play, but the stranger says never mind, this fiddle does the playing for you.

With that Jock sees that this twilight man must be one of Elvenkind. The cow's milk is wanted for some human child they've stolen. Now the fairy gold, if he takes it, could turn to grass and leaves tomorrow. But a magic fiddle's a magic fiddle; wherever you go people will give good money for music. So he says, "I'll take the fiddle."

And, sure enough, when the exchange is made, the fairy takes the cow, and walks right up to the side of the hill, and raps with his staff three times. And the hill opens up, and fairy and cow disappear into it, right into Elfland.

As for Jock with his fiddle, he never knows a day's hungerbut he never knows a day's rest, neither, with folk from one end of the country to the other calling on him for music for dances and weddings and such. His goodwife sees only his money, for he's never at home now. Oh, and every Beltane night, which is Fairies' Holiday, Jock goes to that same hillside and plays, and out come a host of gorgeous folk that are the lords and ladies of Elfland, and they dance to Jock's fiddle all night long, until his arms ache and his fingers are sore.

The way I see it, that's no way to live. He'd have done better to keep the cow.

But, then, I'm a plain man. A crofter, living high in the hills above Leader Water with one wife, many sheep, few neighbors. I don't even see a cow but twice a year at Earl's Market.

I'd never seen anything like the Rhymer before he appeared on our doorstep.

It was one of those dismal autumn nights, with the wind whistling like a mad huntsman calling up the Hounds of Hell, and you know there's rain toward. And sure enough it came, battering at the roof and shutters, and not a little down the chimney so the fire smoked up the place. But there sat my Meg, nice as you please, sewing at a shirt for her niece's eldest down Rutherford way. I was doing a bit of basket - mending, glad that the flock were well penned up already this rough night. Between the rushlight and the fire's glow we could see to work, or maybe it was our fingers rememberi ng the way of it. Lately, light s not as bright as once it was.

Then the dog at my feet. Tray it would be, son of old Belta that was. Tray goes stiff like he's heard something, though my ears caught nothing over the racket of wind and rain. "Soft, there, lad," I say, like you do to a dog that s spooking. "Easy, lad. Silly hound, scared of a bit of weather."

My Meg looks up. "Oh, Gavin," she says, her voice strong against the noise of storm. "Gavin, it's a night for the dead to ride, and no mistake."

She sounded like she was readying to tell one of her tales. Tales go well with dark nights; like the one of that restless spirit, the Lord of Traquair, that rides on stormy nights seeking the wife he murdered in a jealous rage, looking to beg her innocent pardon... but her body's long, long in the mold, and her blessed soul in Heaven. It happened not a day's walk from here, across the river, some years gone by.

"The Wild Hunt rides tonight." Meg's eyes glinted with her eerie tale. "They ride on horses with nostrils like burning coals, chasing the souls of the wicked, that cannot rest for" Then her head came up sharp. And, "Gavin," she says, "there's knocking at the door."

I thought her saying it was still part of the tale. Then I heard it too, a thud too regular for wind and rain.

Tray was growling at my side, his hackles raised. I kept one hand on his head, for there's no telling who might be abroad on such a night: or gypsy, or vagrant, or fiend from Hell. I took light in my other hand, and went and unbarred the door, good Tray by me.