A Note on the Author

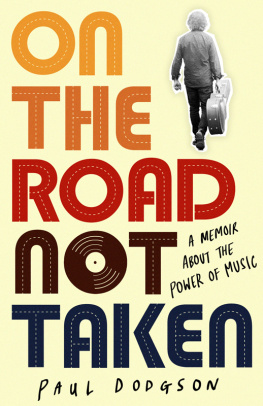

Paul Dodgson is a writer, musician, teacher and radio producer. He has written extensively for theatre, television and radio. On The Road Not Taken is his first book.

For Poppy and Fred

Contents

Introduction

In the year 2000 my father contracted lung cancer. One day I visited him at Guys Hospital in London after he had undergone a major operation. As we sat together by a window and looked out across the city, he began to tell me about an episode of his life I knew nothing about. It was the late 1940s, and he had recently qualified as an engineer with a love of mechanics and a passion for inventing new machines. He spent eighteen months in the city, employed by a Norwegian entrepreneur, designing a fabric printing press they hoped would revolutionise the clothing industry. As he spoke, it was as if his city came to life. I could see the bomb sites, feel the thick London smog, and I sensed his frustration at the machine that never quite worked. And that is when I realised how little I really knew about his life. Dad died soon afterwards and his stories died with him. He had never written them down. That is when I began to write stories from my own life and became interested in learning how other people had written theirs. One thing is certain: this is my story, told from my point of view, so to anyone else involved who sees it differently, I apologise. Most of all I realise this is a story , not a dry record of the facts. This means the past has been edited, significant events left out and others illuminated by research. Real life is often a messy thing that we might wish to be more like a story that adheres to a structure and resolves at the end. One criticism of stories I often hear when writing for radio or television is they should be more real. I suppose, ultimately, a memoir is an amalgamation of the two, creating a coherent story out of the messiness of life.

Writing this book has taught me so much about stories and the power of music. I am not only left with a renewed sense of awe and respect for the musicians who have walked me through the years, but also of how wonderful it is to make music too.

Islands in the Stream, 2013

On a luminous evening in May I take to the road, heading upcountry from Hugh Town to Carnwethers, stopping to watch swallows cut through the air over an abandoned flower field, the birds swooping low over untidy rows of daffodil stalks. The roadside verges are teeming with wildflowers and now the airport has closed for the night there is delicious music in the air, made of soft wind and birdsong. From high on the hill, I look across the ocean toward the silhouette of Bishop Rock Lighthouse, where the sea is sparkling and low sun ignites the clouds. For the last few years Ive been coming to the Isles of Scilly on short teaching assignments and I love this place, twenty-eight miles into the Atlantic and seeming like a world apart. There are friends here, and tonight Im headed for a party to mark two of them going away. Patrick and Lisa have painstakingly restored an old wooden boat and are about to sail off to another life on the mainland.

When I arrive, everyone is in the conservatory on the side of the house, so I let myself in, locate the booze table and open a beer. I am busy catching up when Lisa calls us to order. In Ireland, when we have a party, everyone sings a song. So Ill begin. And she does with an Irish folk song thats unaccompanied, fragile and beautiful; no ornamentation in her voice, just a tune that carries the words, and the words tell a story. Others follow her lead. The owner of a guest house in town picks up a guitar and sings a few songs. They are simple and lovely, each new song a celebration. The music binds us together, turning the partygoers into a little community. It seems the most natural thing in the world until it comes to my turn.

Whatll you sing for us, Paul? says Lisa. There is silence as everyone looks in my direction.

Ill have to let this one pass, I reply. Im sorry but I dont have a song.

It haunts me not to have a song. It haunts me late that night when I walk through the pitch-black lanes to Hugh Town. I think of all the chances to sing and never having done so. I remember, twenty years ago, staying at a hostel in Byron Bay on the east coast of Australia, and walking into a lush, subtropical garden full of backpackers talking, laughing and drinking. In the middle of the garden was a small stage with a PA where travellers could do a turn. I looked on as a young guy wandered on stage, bottle of beer in hand, looking as if he had spent the day surfing and had come straight off the beach. He was slender and unshaven with straggly blond hair and a faded T-shirt. Plugging in a guitar, he sang softly, close up to the microphone and, gradually, everyone in the garden quietened to listen. The sun was setting into dark clouds; there was a hint of sea on the breeze; there were lightning flashes from a distant storm above the hills; his fingers picked the strings; his soft voice carried through warm air. The young singer bound the moment together with his quiet song, so the sunset, the distant storm and all of us in the garden fused into a fragment of time that stands out from all the others.

As I think of it again, walking through the chill night air on Scilly, I remember how I wished, I really wished, I could walk on stage too. Not being able to do so haunted me then like it haunts me tonight. Why cant I? For the last thirteen years I have made part of my living writing music for theatre shows. I have written songs for other people to sing and yet I dont know any mine or anyone elses all the way through. I am fifty-one years old and in the far-distant back of my mind carry the dream of a troubadour life as I have done for the last three decades. And yet I cant even sing at a party. The truth is, and I can barely admit this to myself, I am terrified of singing in public, suffer from stage fright and, worst of all, dont really think I can sing at all.

Next morning when I pull back the curtains and look across the harbour, the haunted feeling is still there, and it stays with me when I take the little plane over the wild Atlantic to Lands End, and on the train all the way up the line to my home in Bristol.

Something has to change.

Puff, the Magic Dragon, 1967

This story really begins long, long ago in the south of England, in a town on the coast of the county of Kent. Today is a bitterly cold Saturday morning in the middle of winter. A lone dog-walker strides along the seafront with a woolly hat on his head, hands in mittens and a shivering dog on a quivering lead; in the High Street an old man pops into the corner shop for his morning paper and tobacco; in the church on the hill the ladies have arrived for the cleaning rota. Up the hill and back a bit is where we live in an avenue of modern houses. We came here when I was a baby and it is the only home I have ever known. On hot summer days we sit in our back garden and breathe the smell drifting over the town from the Mackeson brewery, or a salt sea wind from the coast, and we listen to seagulls shrieking, and steam whistles from the Romney, Hythe & Dymchurch Railway. But today is the middle of winter and my world is about to change.

Come into our kitchen where I am sitting at our yellow Formica-topped table, dipping a spoon into a milky bowl of cornflakes topped with white sugar. Mum is standing at the cooker over a pan of sizzling bacon, when Dad comes in with a scuttle of coke for the boiler. He stamps his feet on the doormat. I am happy and secure here, at the very heart of everything. The radio is on in the background. A song begins to play. I tune out of the kitchen sounds and listen only to the radio. It is as though I am drawn into a parallel world, the world of the song. It is that powerful. The song tells the story of a dragon called Puff and his friend who is a little boy. Soon Puff, the Magic Dragon is the only thing I can hear. The words are carried by a melody that seems sad even before the story takes a sad turn. When the boy in the song grows up and forgets about the dragon, the happiness of the morning ebbs away like the tide going out on the shingle beach at the seafront. I dont know what has happened. How could a morning be turned on its head by a song on the radio? How can a song change the shape of a day?

Next page

![Billy Ray Cyrus - Old Town Road [Remix] Sheet Music](/uploads/posts/book/348571/thumbs/billy-ray-cyrus-old-town-road-remix-sheet-music.jpg)