Contents

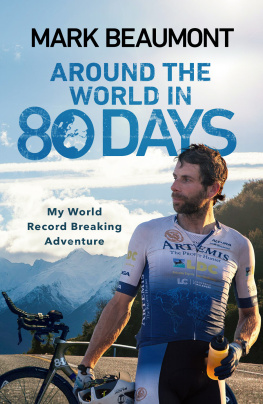

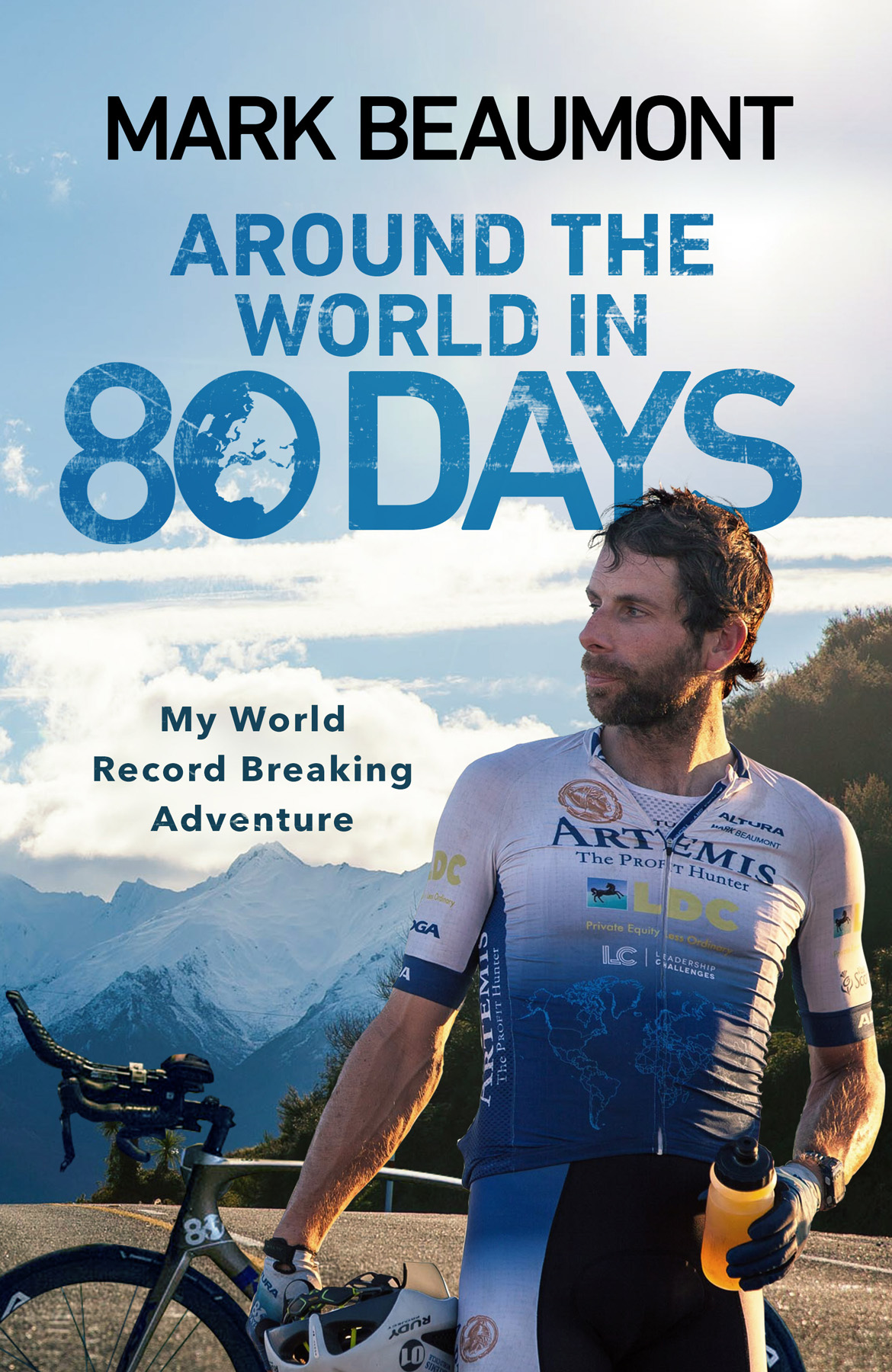

Around the World in 80 Days

My World Record Breaking Adventure

Mark Beaumont

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright Mark Beaumont 2018

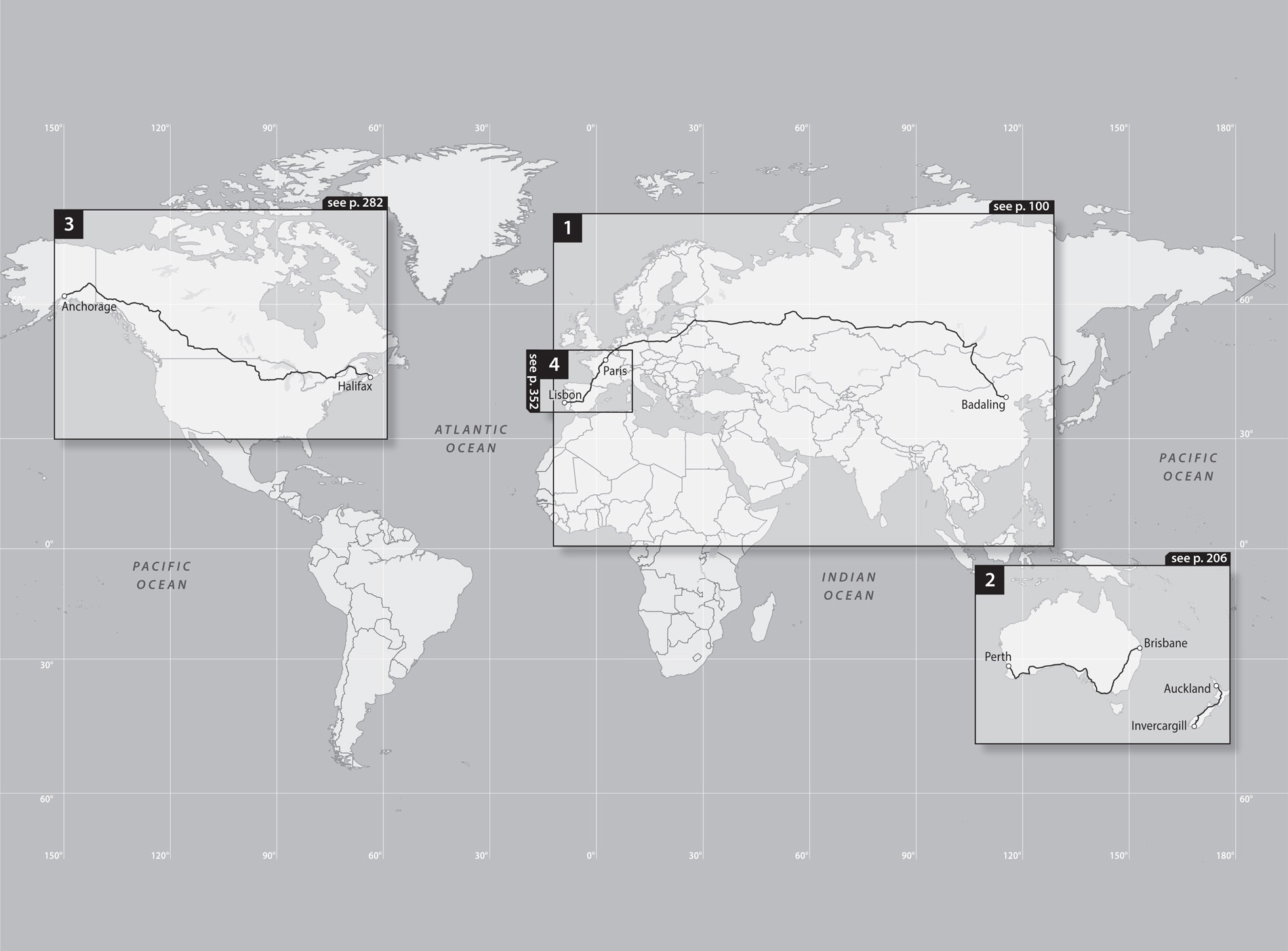

Maps Lovell Johns Ltd

Cover photographs Johnny Swanepoel Design by Richard Shailer/TW

Mark Beaumont has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All photographs Johnny Swanepoel.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Version 1.0 Epub ISBN 9781473559431

ISBN 9780593080412

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

With love to Nicci, Harriet and Willa

Prologue

Id like to think that Jules Verne would have laughed and loved the audacity of someone powering himself around the planet on a bicycle in fewer than eighty days.

The 145-year-old fiction of Around the World in 80 Days has now become a reality in a way Vernes Victorian readership wouldnt have believed possible. But it has to be said that an audience in the first half of 2017 remained hard to convince, even though the plan, on paper, looked simple enough.

To get around the world in 80 days, I needed to average 240 miles a day. Imagine pedalling from the Forth Road Bridge to Liverpool, or London to Plymouth, or more than New York to Boston, every day for two and a half months. To make this sustainable, every single day youd have to be in the saddle for sixteen hours and get about five hours sleep.

My team set about obliterating the previous 18,000-mile circumnavigation world record of 123 days. And we came full circle in a time of 78 days, 14 hours and 40 minutes, working off a plan of seventy-five days riding, three days of flights and two days contingency we just didnt use the entire contingency.

Now that I have written the conclusion on the first page, we can get down to business. Behind the headlines and the hype, and before I have told the story a thousand times, I want to catalogue what this project actually felt like, how glorious but terrifying it was and that was before I turned a single pedal. I also want to acknowledge properly that, like the front man in a band, I get the lions share of the profile and credit for what was actually an amazing team performance.

As I write this prologue, just months after the finish, there is already a sense of inevitability about the 80 Days, as if it were always on the horizon, the next prize to be claimed in endurance cycling. No, it wasnt. People thought it was a crazy ambition. Success only looks inevitable with the privilege of retrospect. There was no reference point for riding this fast, nothing in the history of endurance cycling that people could latch on to and say, Well, if that was possible, this should be possible. I was asking people around me to believe in a massive leap in performance, and that takes a quiet confidence in your ability, a healthy dose of obsession and a bloody good plan.

The romantic notion of record-breaking is that you throw everything at the impossible and figure out what is possible. You figure out physically what you are capable of and mentally how strong you are in the heat of battle. The reality is that after years of planning, we read a plan from a script. That rather mundane description doesnt seem to account for all the rotten luck, including four crashes, serious storms and delays on borders, not to mention the uncertainty of even getting to the start line. Being more objective, we must have had as much good luck as bad luck.

Let me say up front, I will not be cycling around the world a third time. This is the first time in my career I feel like I have nothing to prove to myself in terms of endurance, that the 80 Days was not a stepping stone to whats next. Despite the self-limiting logic of our target, this really does feel like my personal best. I suffered hugely, and my teams commitment to the task was incredible to witness. Furthermore, I would happily mentor anyone who wants to break my record. I am not precious about it in the slightest. In fact, I applaud the audacity of whoever comes next.

Since my return to Paris on 18 September 2017, the reaction from the worlds press and the public has been extraordinary. After living in a performance bubble for months, to stop and appreciate the wider perspective on my teams furious progress, and the interest in it, has been incredible. But why would so many people care how fast I can ride a bicycle around the world? And I am not talking about the cycling press. Why would the Financial Times write five features on this human endeavour, and why would the finale be watched by over 300,000 people on Facebook? Maybe because we are all fascinated by human aspiration, with one eye on the mirror, wondering what we are capable of. Its a perspective on our own personal milestones.

Pedalling the planet in under eighty days makes our world seem both gigantic, when I remember the endurance and suffering, and somewhat smaller than before, when I zoom out to consider the entire race. I certainly hope it is a journey that gives people confidence of their own to be bold, to be disruptive (in a good way), to attempt to redefine what is possible.

Part One

Before the World Began

1

Why the World?

Full circle, back to the bike.

At home in Scotland, the newspapers always refer to me as a cyclist and adventurer, normally in that order. However, for the decade since graduating from Glasgow University with a perfectly useful Economics and Politics degree I have been pedalling for a minority of that time, having spent years rowing boats, exploring the Arctic, climbing mountains, fundraising for charities, working with corporate businesses and being a TV person in numerous guises.

In August 2014, when I first floated the idea with my wife Nicci to come back to life on two wheels, I was in the worst shape of my adult life. The eleven days of sport at the Glasgow Commonwealth Games had just come to a close and I had spent the preceding nine months abroad, following the Queens Baton Relay to sixty-eight nations and territories, telling the inspiring stories of hundreds of competitors for BBC World. Elite and aspiring athletes constantly surrounded us, but for my cameramen, director and me, this was a feat of airport and hotel endurance, red carpets and the corresponding feasting. I did attempt to run 10km in every Commonwealth country, but looking back, this was a two-year sabbatical in my athletic career.