The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In the past four decades, numerous Holocaust survivors have published their memoirs. Some waited to write until they reached an age at which people, in general, are more prone to reflect on the past. Some wrote because they felt the world was now more attuned to listening to what they had to say about this genocide. Others were urged to do so by their children, if not grandchildren. Since the 1980s so many memoirs have been published that it is easy to forget that this desire to write and record began far earlier.

In fact, Holocaust survivors have been writing their memoirs and giving their testimonies since the very end of the war. By the early 1960s, fifteen years after the end of the Holocaust, there were thousands of survivors memoirs in print. In 1961, when Elie Wiesel sought an American publisher for Night, which had already been published in French, many rejected it because they believed there were too many memoirs in circulation. In his introduction to the French edition of Night, Nobel Prize winner Franois Mauriac acknowledged that Wiesels was one among a myriad of Holocaust memoirs when he wrote, this personal record coming as it does after so many others (emphasis added). Sadly, with the passing of the generation of survivors, that trend is nearing its end.

It is sometimes hard to imagine that these recollections, now much treasured and valued, were once eschewed by historians who preferred documentsdespite the fact that most of these documents were products of the Third Reichto personal accounts. These historians worried that personal memories were not as trustworthy as documents. Todays historians recognize the value of these works, particularly when they are juxtaposed with the documentary and material evidence.

There are, of course, a number of methodological problems entailed in relying on these memoirs and testimonies. They are written ex post facto. Memory is elusive. It is impacted by more contemporary events. An individuals recollection of an event may be colored by how another person who was also present remembered it. A survivor may recount the details of an event in order to stress a particular point, a point whose importance only became evident to her well after the fact. This is true, of course, with any memoir or testimony. We write to make a point. It is particularly true when the memoir deals with a traumatic event. And what could have been more traumatic than the Holocaust?

Moreover, memoirs are the voices of those who survived, not those who did not. It was with good reason that David Boder, one of the first scholars to systematically record survivors accounts of their experiences, entitled his work I Did Not Interview the Dead. He knew that the voices he recorded were of the ones who survived. The voices and recollections of those who were not lucky enough to endure were, in the main, lost to us forever.

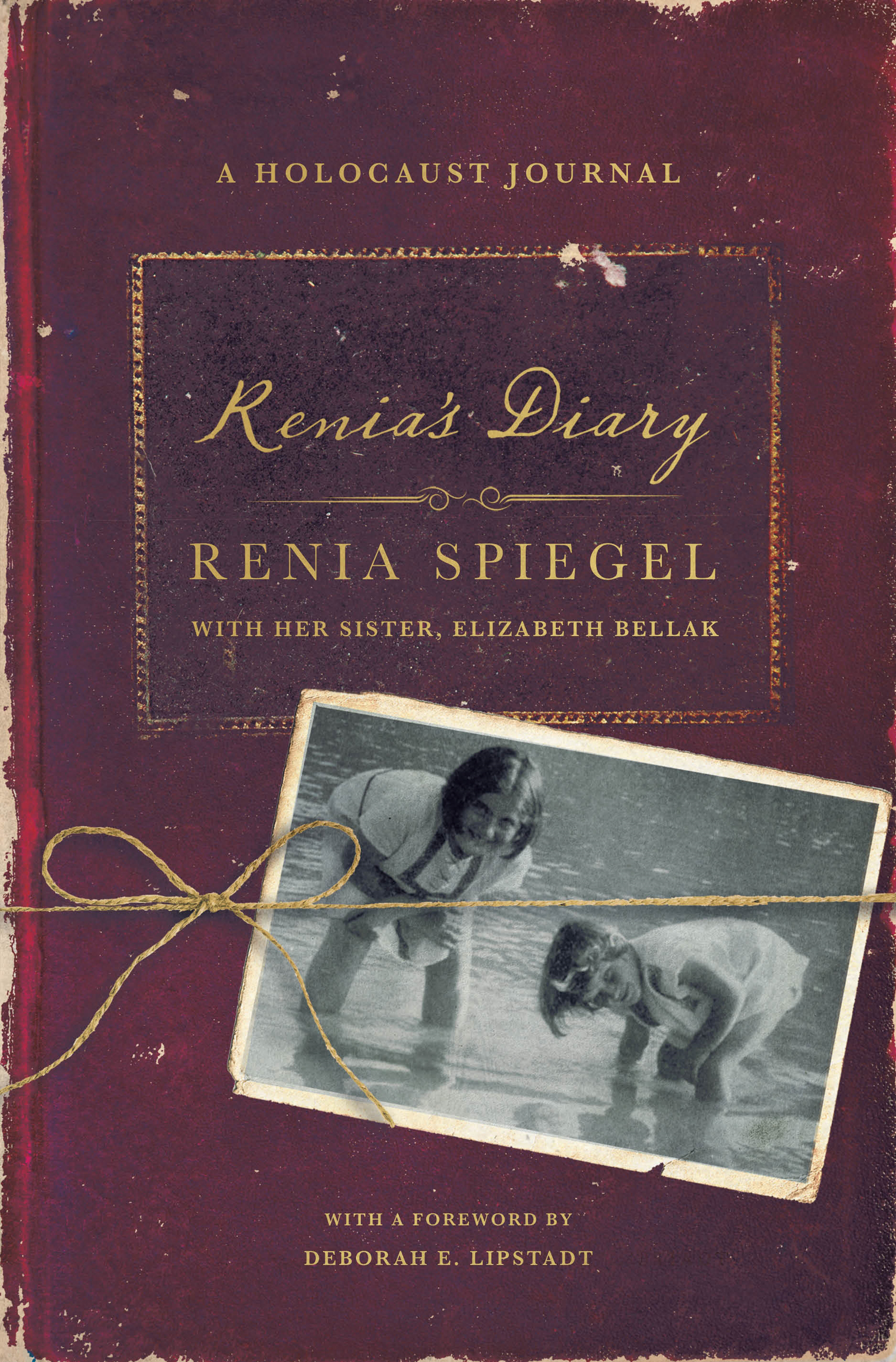

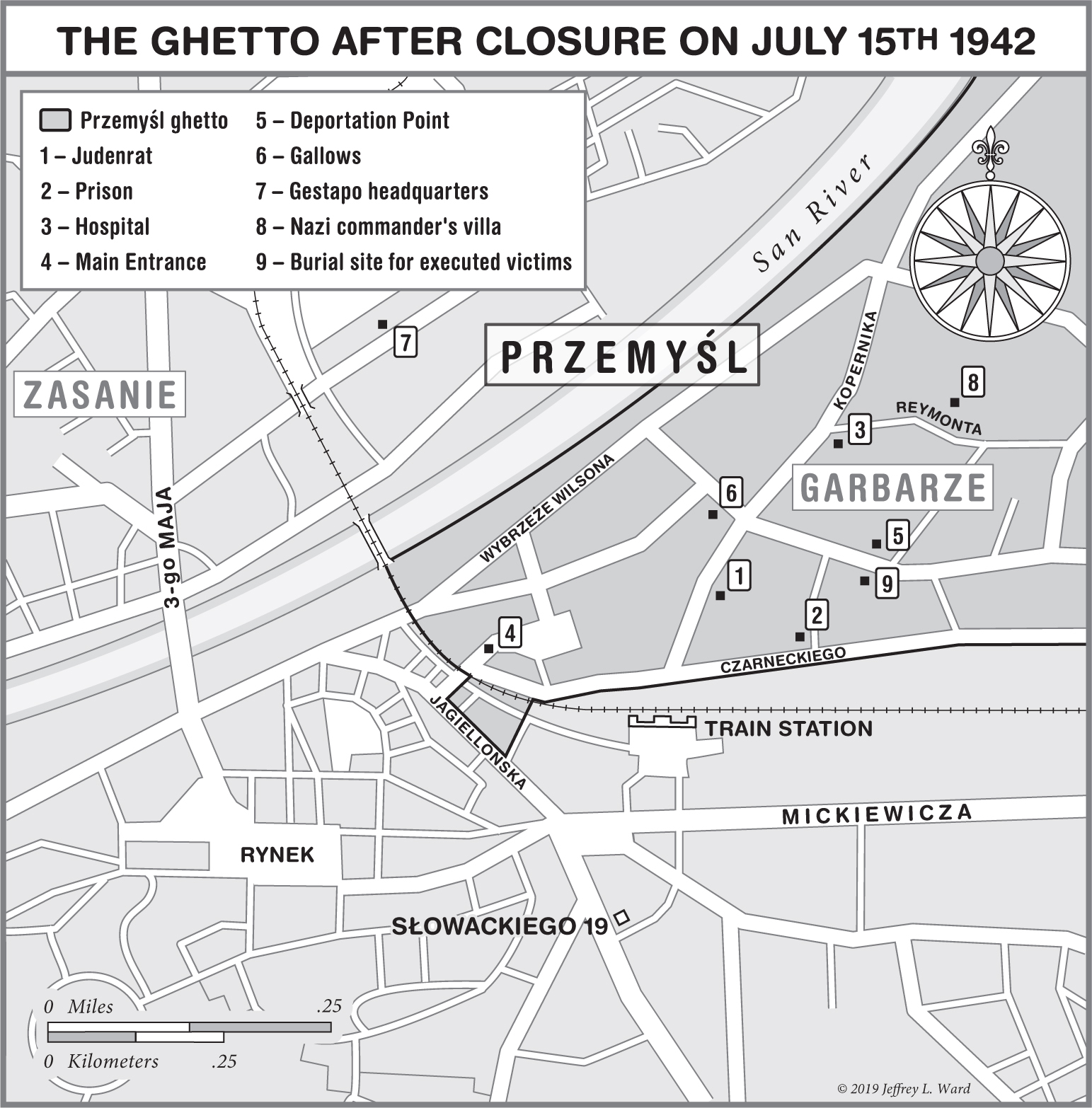

I write in the main because we do have some of the voices of those who perished in the form of diaries such as Renia Spiegels. Diaries are different, not only because they allow us to hear the voices of those who did not survive. They are different from memoirs because they do not pose these methodological challenges. Irrespective of whether they were written by someone who survived or someone who did not, they are fundamentally different from memoirs because they are contemporaneous accounts. Simply put, the author of the memoir knows the end of the story. The diarist does not. The diarist may well be unaware of the bigger picture of what she is experiencing. For example, is the creation of a ghetto in her town part of a broader policy of ghettoization or just something happening where she is? Whereas the person writing after an event may have a sense of how a particular German decree fit into overall Nazi policy, the diarist generally does not. What may seem to be of relatively little importance to the diarist may, in fact, turn out to be of great significance. And conversely, what may seem utterly traumatic to the diarist may pale in comparison to what will follow.

Most important, diaries offer us something that memoirs do not: an emotional immediacy. And it is this immediacy that is so very compelling. I am reminded of Hlne Berr, the Israeli young Parisian woman who kept a diary from 1942 through to the day she and her parents were rounded up in March 1944. Fortuitously, she begins to write but a short time before the decree that all Jews must wear a yellow star. She confides to the diary her struggle with whether to wear it or not. Was wearing it an act of compliance with a hateful regime or did it demonstrate a pride in ones Jewish identity? We read of her reactions to passersbys comments. Some express solidarity and others pity. She reflects on them, not from a distance of many years, but on the day she encountered them. She does notbecause she cannotcontextualize this act as the first step in an array of far worse persecution to come.

In reading Renia Spiegels diary, I was also reminded, as will be many readers, of Anne Franks iconic work. All three of these diariesSpiegels, Franks, and Berrsare filled with the seemingly mundane musings of young girls who are transfixed by first loves and filled with hopes for the future. Renia Spiegels diary is replete with familiar expressions of teenage angstfirst love, first kiss, and jealousies that, in retrospect, may seem meaningless but at the moment seem, at least to Renia, to be momentous. It is also filled with poetry that cannot help but touch the reader.

We who read her writings are possessed of something she did not have: knowledge of the outcome. At the outset of the diary she is distraught that she has been forced to go live with her grandparents and, therefore, has no real home. It makes her so sad that I have to cry. Not having a home will pale in comparison to what is to come. Had she written a memoir she would have known that fact and might have flattened this traumatic moment. She does not do so. In 1940, after the fall of Western Europe, she cries, Im here on my own, without Mama or Daddy, without a home, poked and laughed at. Oh, God, why did such a horrible birthday have to come? Wouldnt it be better to die? I look down from the height of my 16 years and I wonder whether Ill reach the end. Were she writing a memoir, knowing what was in the offing, she might well have overlooked this moment of despondence. She might not have been so distraught when the luxury of fur clothing was taken from the Jews. Yesterday coats, furs, collars, oversleeves, hats, boots were being taken away on the street. And now theres a new regulation that under pain of death it is forbidden to have even a scrap of fur at home.