Copyright 2019 by Adrienne Brodeur

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brodeur, Adrienne, author.

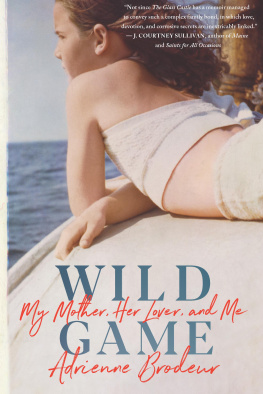

Title: Wild game : my mother, her lover, and me / Adrienne Brodeur.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2019].

Identifiers: LCCN 2019004915 (print) | LCCN 2019013400 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781328519047 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328519030 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358272670 (PA, Canada edition)

Subjects: LCSH : Brodeur, Adrienne. | Brodeur, AdrienneFamily. | Hornblower, Malabar. | Mothers and daughtersUnited StatesBiography. |

Authors, AmericanBiography.

Classification: LCC PS 3602. R 6346 (ebook) | LCC PS 3602. R 6346 Z46 2019 (print)| DDC 813/.6 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019004915

Jacket photograph courtesy of the author

Jacket design by Christopher Moisan

Author photograph Julia Cumes Photography

v1.0919

Gott spricht zu jedem... / God speaks to each of us... from Rilkes Book of Hours: Love Poems to God by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy, translation copyright 1996 by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy. Used by permission of Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

The Uses of Sorrow, from Thirst by Mary Oliver, published by Beacon Press, Boston. Copyright 2004 by Mary Oliver, used herewith by permission of the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency, Inc.

For Tim, Madeleine, and Liam

and in memory of Alan

Authors Note

Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.

GABRIEL GARCA MRQUEZ

In writing this book, Ive endeavored to be as factual as possible, turning to journals, letters, scrapbooks, photo albums, report cards, recipes, articles, and other records of my personal and familial history. But in instances where I could not substantiate a physical or emotional detail, I turned to memory, knowing full well that it is revisionist and that each time we remember something, we alter it slightly, massaging our perspective and layering it with new understanding in order to make meaning in the present.

Wild Game does not pretend to tell the whole storyyears have been compressed into sentences, friends and lovers edited out, details scrubbed. Time has scattered particulars. What follows in these pages are recollections, interpretations, and renderings of moments that shaped my life, all subject to perspective, persuasion, and longing. I am aware that others may recall things differently and have their own versions of events. Ive tried to be careful in telling a story that includes other people who may remember or have experienced things differently.

I have changed the names of everyone in the book except for my parents, Malabar and Paul, and myself.

THE USES OF SORROW

by Mary Oliver

(In my sleep I dreamed this poem)

Someone I loved once gave me

a box full of darkness.

It took me years to understand

that this, too, was a gift.

Prologue

A buried truth , thats all a lie really is.

Cape Cod is a place where buried things surface and disappear again: wooden lobster pots, the vertebrae of humpback whales, chunks of frosted sea glass. One day theres nothing; the next, the cyclical forces of natureerosion, wind, and tideunearth something that has been there all along. A day later, its gone.

A few years ago, my brother discovered the bow of a shipwreck looming from a sandbar. He managed to excavate an ample wedge of hull before the tide came in and thwarted his efforts. The following day, he returned to the same spot at the same tide, but all traces of the ship had vanished. Had he not saved that waterlogged slab of wood, knotted and beautifully gnarled, and left it to dry on his lawn, he might have imagined hed dreamed the whole thing.

Blink, and youll miss your treasure.

Blink again, and youll realize that the truth you thought was safely hidden has materialized, some ungainly part of it revealed under new conditions. We all know the adage that one lie begets the next. Deception takes commitment, vigilance, and a very good memory. To keep the truth buried, you must tend to it.

For years and years, my job was to pile on sandfistfuls, shovelfuls, bucketfuls, whatever the moment necessitatedin an effort to keep my mothers secret buried.

Part I

Oh, what a tangled web we weave.

SIR WALTER SCOTT

One

Ben Souther pushed through the front door of our Cape Cod beach house on a hot July evening in 1980, greeting our family with his customary, enthusiastic How do! In his early sixties at the time, Ben had a full head of thick, white hair and callused hands that broadcast his love of outdoor work. I watched from the hallway as he back-patted my stepfather, Charles Greenwood, with one hand and, with the other, raised high a brown paper grocery bag, its corners softening into damp, dark patches.

Lets see what you can do with these, Malabar, Ben said to my mother, who stood in the entryway beside her husband. He presented her with the seeping package and gave her a peck on the cheek.

My mother took the sack into the kitchen and placed it on the butcher-block counter, where she unfolded the top and peeked inside.

Squab, Ben said proudly, rubbing his hands together. A dozen. Plucked, cleaned, I even took off the heads for you.

Ah. So the wetness was blood.

I glanced at my mother, whose face registered not a trace of revulsion, only delight. She was, no doubt, already doing the math, calculating the temperature and time required to crisp the skin without drying the meat and best coax forward the flavors. My mother came to life in the kitchenit was her stage and she was the star.

Well, I must say, this is quite the hostess gift, Ben, my mother said, laughing, appraising him with a tilt of her chin. She gave him a long look. Malabar was a tough critic. You had to earn her good opinion, a process that could take years and might not happen at all. Ben Souther, I could tell, had gone up a notch.

Bens wife, Lily, followed close behind, bearing a bouquet of flowers from their garden in Plymouth and a bag of wild watercress, freshly picked from the banks of their stream, peppery the way Malabar loved it. About a decade older than my mother, Lily was petite and plain-pretty, with graying brown hair and a lined face that spoke of her New England practicality and utter lack of vanity.

Charles stood on the sidelines smiling broadly. He loved company, delicious meals, and stories from the past, and this weekend with his old friend Ben and Bens wife, Lily, promised an abundance of all. Id known the Southers since I was eight, when my mother married Charles. I knew them in the way that a child knows her parents friends, which is to say not well and with indifference.

I was fourteen.

The cocktail hour, a sacred ritual in our home, commenced immediately. My mother and Charles each started with their usual, a tumbler of bourbon on the rocks, had a second, and then progressed to their favorite aperitif, which they called the power pack: a dry Manhattan with a twist. The Southers followed my parents lead, matching them drink for drink. The four of them meandered and chatted, cocktails in hand, from the living room out to the deck and then, later, across the lawn to the wooden stairs that led down to the beach. There they enjoyed the coastal abundance before them: brackish air, a sky glowing pink with sunset, the ambient sounds of seagulls, boats on moorings, and distant waves.