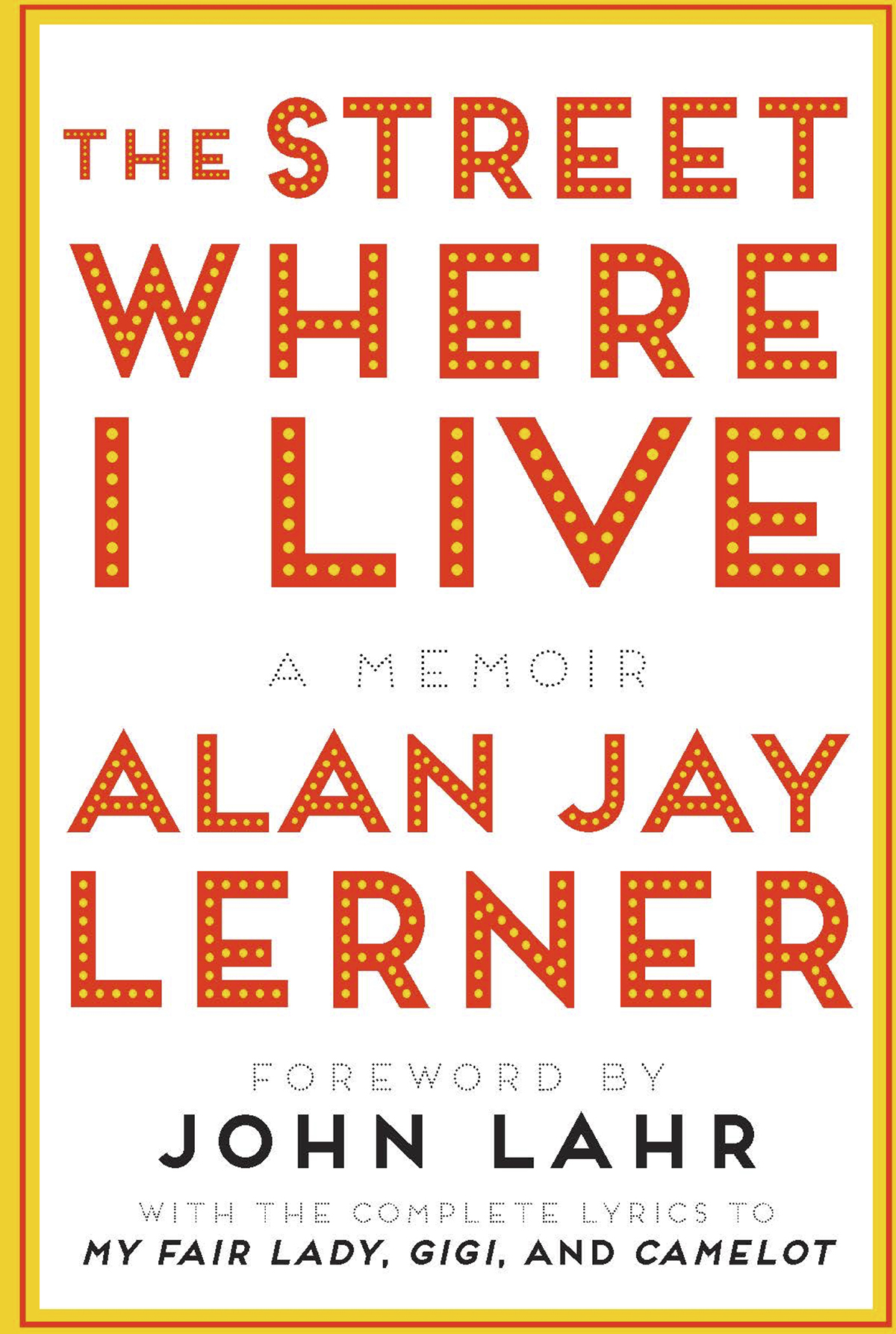

The Street Where I Live

A MEMOIR

ALAN JAY LERNER

Foreword by John Lahr

Copyright 1978 by Alan Jay Lerner

Foreword copyright 2018 by John Lahr

Originally published as a Norton hardcover 1978; published as a paperback 1980, reissued with a new Foreword 2018

My Fair Lady

Copyright 1956 as renewed, by THE ALAN JAY LERNER TESTAMENTARY TRUST and THE FREDERICK LOEWE FOUNDATION

Chappell & Co., Inc., administrator of publishing throughout the world.

International Copyright Secured.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, including public performance for profit

Used by permission of Chappell & Co., Inc.

Gigi

Copyright 1957 & 1958 by Chappell & Co., Inc.

International Copyright Secured.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Used by permission.

Camelot

Copyright 1960 as renewed, by THE ALAN JAY LERNER TESTAMENTARY TRUST and THE FREDERICK LOEWE FOUNDATION

Chappell & Co., Inc., administrator of publishing throughout the world.

International Copyright Secured.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, including public performance for profit

Used by permission of Chappell & Co., Inc.

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Fearn Cutler de Vicq

Cover design by Yang Kim

ISBN 978-1-324-00165-2 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-393-35613-7 (pbk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To Fritz,

without whom this would have been

an address book.

Contents

A lan Jay Lerner described his job this way: I write musicalsevery word spoken or sung from curtain up to curtain down. But Lerners songs, not his stories, are what live after him. In the late 1940s, when Lerner hit his stride as a lyricist, America was enjoying the greatest rise in per-capita income in the history of Western civilization. Between 1945 and 1955, individual wealth nearly tripled. Lerners lyrics were part of the luster of this Golden Age; his witty eloquence made the high times sparkle. In such memorable musicals as Brigadoon , Paint Your Wagon , My Fair Lady , Gigi , and Camelot , Lerner whipped up verbal souffls to accompany the buoyant melodies of Frederick Loewe and put before the American public a glamorous sense of its own well-being. Lerner insisted on joy; he even incarnated it in the happily-ever-aftering of Camelot, an Eden where the climate must be perfect all the year. To our sour age, in which frivolity has been more or less banished, such fantasies may seem antique. But if the fifties and early sixties were the belle poque of American musical theatre, as Lerner claims in his memoir, then he was one of the most radiant belles of the ball.

Lerner was a Park Avenue princeling; he exuded the optimism of his privilege. Although Lerner lived in many deluxe homes through the decadesa Manhattan townhouse, a villa in the South of France, a colonial farmhouse in Rockland Countyhis permanent residence was in the Superbia of his imagination. His father, Joseph, owned a successful chain of womens specialty stores; Lerners emporium was Broadway. He imposed on his lyrics and on his troubled life the shellac of charm. I can never find it in my heart to despise glamour, Lerner said. His particular lyrical line was longing, not loss. As a rule, it is not sadness that brings tears to my eyes but a longing fulfilled, he said. His impeccably crafted lyricsthe title song for On a Clear Day You Can See Forever , for instance, took ninety-one drafts and nearly a year to completemade an exhibition of perfect equipoise.

Lerner grew up his fathers favorite of three boys in a fractious family. My Pappy was rich and my Ma was good-lookin but by the time I was born my father no longer thought so, he writes in his memoir. Their life together was a familiar symphony in three movements: arguing, separating, reuniting. Lerner identified more with his high-rolling father than with his roly-poly mother, Edie, who once slapped him because he looked like her husband. I adored him, Lerner said of his misogynistic old man. (Of Edie, he observed, My mother didnt start really loving me until after the success of Brigadoon .) Lerner regularly accompanied Joseph to boxing matches and, from the age of five, to musicals. (He had been named after the insolent Hearst drama critic Alan Hale.) His obsession with language and its meticulous deployment also began with his father. Joseph dispatched his children to Bedales, the exclusive British boarding school, to acquire proper use of their mother tongue. I never sent him a letter that he did not return to me with notes in the margin suggesting more interesting ways of saying the same sentence, Lerner recalled.

Lerner carried his fathers preoccupations (musicals, language, boxing, philandering) and his high expectations into adult life. In the mid-fifties, Joseph, at the hospital for his fiftieth operation for throat cancer, which had left him unable to speak, scribbled his son a note and pressed it into his hand as he was wheeled into the operating theater. I suppose youre wondering why I want to live? he wrote. Because I want to see what happens to you.

Lerners lyrics were exercises in seduction, a way of recapturing the adoration in Josephs defining gaze. Lerner, who had lost an eye while boxing at Harvard, literally had an eye for the ladies. He was a courtly lover. He married eight times. Alan was a broken man inside, his third wife, the Academy Awardwinning actress Nancy Olson, whose marriage to Lerner spanned his most creative period (195057), told me. The only way he could feel whole was when the eyes of another were on him. Another of his ex-wives quipped, Marriage was Alans way of saying goodbye. The glow of idealization was the intoxication of courtshipalmost like being in love, as Lerner famously admitted in song. About the affairs of his restless heart, his memoir is weasel-worded. The heart may have its reasons of which the reason knows nothing; but reason all too often has no heart, he wrote. Elsewhere, however, he confessed, I wanted the thrill of love, not its disappointments.

Lerner also had trouble being faithful to his collaborator Fritz Loewe, which became an issue between them. When they formed their partnership, in 1942, after a chance meeting at the Lambs Club, Lerner was an eager beaver of twenty-four; Loewe, at forty-one, was a veteran of disappointment. Lerner was fast-talking, fast-thinking, fast-movingin other words, American. Loewe, who was Austrian and whose father had been a star of Viennese operetta, was cultured and sardonic. He had been a child prodigy, had made his solo piano debut with the Berlin Philharmonic at fourteen and, at fifteen, wrote Kathrin (The Girl with the Best Legs in Berlin), the sheet music for which sold two million copies. Perhaps because hed struggled so hard and so long to find a theatrical foothold in America, Loewe was given to loudly proclaiming his genius. (He was the single most conceited man I ever knew, said Andr Previn, who was the musical director of Gigi , and for whom Loewe wrote some of his lushest melodies.)

Next page