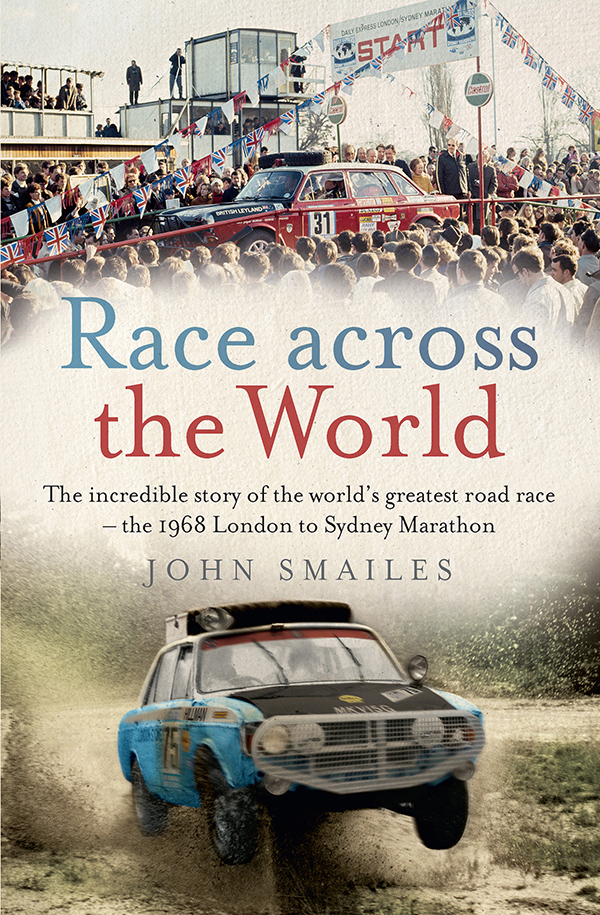

JOHN SMAILES is a journalist, motorsport commentator, publicist and, until recently, proprietor of a specialised communications agency. He co-wrote Climbing the Mountain, the autobiography of Australian motorsport legend Allan Moffat OBE, and the sixtieth anniversary history of the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport. In 1968, as a young staff writer for the Sydney Daily Telegraph, he was assigned to cover and help organise the LondonSydney Marathon. With the Telegraphs motoring writer David McKay he wrote a book on the adventure entitled The Bright Eyes of Danger. Fifty years on Race across the World is its sequel.

First published in 2018

Copyright John Smailes 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 253 3

eISBN 978 1 76063 788 0

Maps courtesy of Daily Express/Express Syndication, UK

Index by Puddingburn

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Luke Causby / Blue Cork

Front cover photos: Getty Images (top); Rootes Group (bottom)

For

Tommy Sopwith, who invented the marathon

Andrew Cowan, Brian Coyle and Colin Malkin and the 97 other crews who set out to race across the world

Jenny, who was there even then

Contents

THE CRASH WAS DELIBERATE.

The small man, grey hair cut short, with eyes so piercing they drill you, was unwavering in his assertion.

The car that hit us was deliberately there. The crash was not normal.

We had met in a cafe in Marseille airport, a happy place decorated in the manner of the sixties.

Jean-Claude Ogier and his wife, Lucette, had driven up from their holiday home at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and Id flown in from the UK on a tight schedule. Theyd brought their nine-year-old granddaughter, Juliette.

Our meeting was to review their part in the greatest road race of modern timesthe 1968 LondonSydney Marathon.

Ninety-eight crews raced across half the world in pursuit of a total prize purse of 22,650a huge sum fifty years ago, equivalent to more than 275,000 or almost $500,000. But it was inconsequential compared to the glory of crossing the line first.

Ogier had almost won it.

Driving with Belgian ace Lucien Bianchi, winner of the Le Mans 24 Hour race only two months before, the Frenchman was in sight of victory. The pair had kept their lightweight Citron DS 21, a real rocket, in touch with the lead all the time. Theyd been third at Bombay and across Australia had kept their head as a firestorm of desperate competition burst out around them. Across 5600 kilometres of the worst roads and tracks Australias rugged outback and alpine regions could throw up, theyd set a cracking, but not attacking, pace.

That tactic had delivered them outright first, but it was tenuous.

At midnight on the last day of competition, after more than 16,000 kilometres, just 12 points separated the top six competitors.

Bianchi and Ogiers gap on the field was only 2 minutes and each minute was worth a point. It was too close to call and there were 694 competitive kilometres remaining.

Bianchi, the lead driver, took the wheel.

He was tempted to go on maximum attack, as he was certain those chasing him would do. But that would be foolhardy. A slip off the road would spell disaster. He had everything to lose, nothing to gain.

But he could also not afford to back off. A last-minute lunge by any of the worlds best long-distance race and rally drivers could eradicate his slim advantage. All he could do was drive the Citron as hard as he knew how, with maybe a miniscule margin for error in reserve. There was sparse light from the waning crescent moon to give texture to the tall trees lining the undulating roller-coaster of a track.

Bianchi, Formula One driver, sports-car ace, rally expert, was masterful that night. Ogier, co-driver and nominal navigator although they had no pace notes, sat in awe as the slightly built, moustachioed professional guidednot flungthe Citron towards the dawn.

When they reached Hindmarsh Station, the last competitive stage on the near 17,000-kilometre journey, they were 11 minutes ahead. Bianchi had massively consolidated his lead.

Behind them the field had broken down, blown up, crashed and changed position, but theyd not caught the Citron. It had been a night of legend, a fitting climax to a glorious adventure. The marathon, conceived in the UK to showcase the ailing British motor industry, had instead humbled the best cars from both that nation and Australia.

A French car was en route to victory.

Just two stages remained, each of around 165 kilometres, one mostly on gravel from Hindmarsh Station up to Nowra near the south coast of New South Wales, and the other on the national highway to the Warwick Farm Grand Prix circuit outside Sydney where the final route card would be stamped. Both were time certain but neither required effort. They were essentially transport stages, capable of being cleared without loss of points, unless, of course, disaster struck. It was the expectation of all the crews that the real marathon had finished at Hindmarsh Station and that they would now cruise to the finish.

Their job was done; their positions were set.

Ogier took over the wheel, and a tired but extremely satisfied Bianchi settled down in the right-hand seat of their left-hand-drive car.

It was early morning, just coming up to 8 a.m., and they had 2 hours 1 minute to cover the distance to the time control outside Nowra, an average speed of less than 80 kilometres per hour. Up through Braidwood in southern New South Wales, the Turpentine Range offered a wonderful, undulating open dirt road. Just 22 kilometres was bitumen; the rest, as they approached the Nowra Road where the control was set on a rickety trestle table under a canvas tent, was loosely graded hard-packed dirt.

Seventeen kilometres back from the control was Tianjara Creek, the last obstacle on the course.

Media from the major newspapers had flown down from Sydney, landed at Nowra and driven in by taxi to shoot the cars splashing through. The afternoon Sun newspaper, a competitor of sponsor and morning paper The Daily Telegraph, was looking to scoop its rival. They were both there, jostling for position. Television crews were on the creek exit. The word had got around. Tianjara Creek was buzzing with spectators.