William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

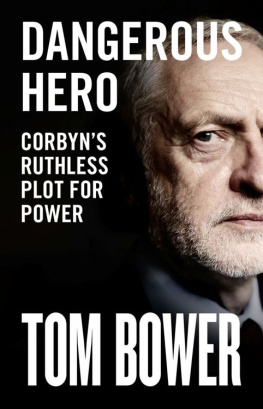

Copyright Tom Bower 2019

Cover image Getty Images

Tom Bower asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publishers have made every effort to credit the copyright holders of the material used in this book. If we have incorrectly credited your copyright material please contact us for correction in future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008299613

Ebook Edition February 2019 ISBN: 9780008299590

Version: 2019-11-11

To Veronica

Contents

Sceptics scoffed at the title of this book, but the turbulence in the Labour Party since its publication in February 2019 has justified the sobriquet attached to Jeremy Corbyn. Contrary to the vote-winning image of an honourable campaigner for a gloriously benevolent society, Corbyns life, as revealed here, is a catalogue of duplicity and dogma. Similarly, John McDonnells career as a virulent Trotskyist poses a warning to Britains honest electors. Over the past months, both men have sought to airbrush their lifelong alliance with tyranny from the public record. This book tears away the disguises they have adopted. Electors should judge them on their footprint. Thirty years after Eastern Europe was liberated from oppression, Britain now stands on the edge of succumbing to a group of Stalinist sympathisers.

Ostensibly, the 2019 election is about Brexit. But in reality, it is a contest between capitalism and communism. A careless vote risks allowing a government led by Marxists to take control of the country by default. And once Corbyn and his trusted associates are in Downing Street there will be little reprieve. The locks will be turned. No Marxist government in history has ever relinquished power democratically.

As students of Lenin, Corbyn and McDonnell entered the general election determined to ignore the fundamental disagreements with many party supporters to promote their lifelong passion to transform Britain into a Marxist state. Echoing Hugo Chvez, their Venezuelan hero, Corbyn and McDonnell offer the most deprived of Britains electorate a bonanza of riches, confiscated from the middle classes. (Britains seriously rich long ago relocated their wealth abroad, far from Corbyns grasp.) Corbyns political manifesto promises that equality of opportunity will be replaced by equality of poverty. His election will hasten the exodus of the countrys wealth creators to more welcoming nations. The aftermath of destroying capitalism is visible in Venezuela hyperinflation and crippling shortages.

Even worse, contrary to Corbyns promises Britain will no longer be a fundamentally decent and tolerant society. Ever since the original publication of this book, the evidence that Labour under Corbyns leadership is anti-Semitic has been irrefutable. As successive Labour MPs resigned in disgust over Corbyns tolerance of their persecutors in their constituencies and in Westminster, Corbyn has shown no shame. With horror, mournful MPs have witnessed the triumph of their persecutors. Chris Williamson, suspended from the party as a suspected anti-Semite, was never expelled. To his victims distress, many traditional Labour MPs meekly collaborated with Corbyn rather than revolt against his racism. Self-interest suffocated the principles so loudly proclaimed by those social democrats formerly the bedrock of the Labour Party. Lenin called them his useful idiots.

Rarely has every individuals vote been more important than in the 2019 general election. The reason is described in this biography of a man who, despite his veneer of virtuousness, is, I believe, a dangerous hero.

The genesis of this book started exactly fifty years ago.

At the end of January 1969, a group of Marxist and Trotskyist students at the London School of Economics led a stormy protest against the schools director, an authoritarian from Southern Rhodesia. He had ordered the staff to close a series of gates inside the building in Aldwych to prevent a students meeting in the schools Old Theatre. In the mle, at about 5 p.m., a caretaker guarding the gates died from a heart attack and the students instantly started a month-long occupation, igniting similar sit-ins across Britains universities.

Throughout that first night of occupation, hundreds of LSE students crowded into the Old Theatre to debate the prospects of a Marxist revolution in Britain. Led by American graduates from Berkeley, California, where the student revolt against the Vietnam War had started five years before, and with speeches from French and German students, battle-scarred from 1968 street fights in Paris and Berlin, LSEs Marxists and Trotskyists (there were many) told us we were the vanguard of a worldwide revolution which would begin with the students, and the workers would follow. We believed it.

Aged twenty-three and from a conservative background, I had completed my law degree at the LSE (the countrys best law faculty at the time), and while studying for the Bar exams was employed on legal research projects at the college. Long before that dramatic night I had concluded that English law protected property rights at the expense of the rights of individuals and real democracy. Surrounded by articulate Marxists studying sociology and government, and going to lectures by Ralph Miliband and other Marxist teachers, I became attracted to their analysis of society. In that era, for anyone interested in politics that was not surprising.

In the wake of the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa in 1960 (I had marched in protest through London with my school friends against apartheid during the early years of that decade) and the anti-Vietnam protests outside the American embassy in Grosvenor Square in 1968 (along with others, I escaped with just some nasty blows from the police), I shared the horror at the dishonesty and disarray of Harold Wilsons Labour government. Added to that, for family reasons I was influenced by events in Germany. In particular I became fascinated by Rudi Dutschke, an erudite Marxist who spoke in graphic terms in Berlin about the long march through the institutions of power to remove the Nazis and their capitalist supporters from ruling post-war Germany. In April 1968 an attempted assassination of Dutschke illustrated the raw battle for power between good and evil raging across Europe and America. (I would meet Dutschke later in Oxford.)

Those days and nights of long debates about politics, the economy and society were decisive for many of us involved in the LSE occupation. After a month it all petered out, but that 1968 generation was marked for life. None of us attained high office in politics, industry or education. Instead, that seminal moment in Britains social history created cynics: men and women who were dissatisfied, curious, nonconformist and determined to expose evil in the world, of whatever type and wherever it might be found.

As Tommy the Red (I became a students spokesman), that month I learned many vital lessons for the journalistic career I embarked on soon after, travelling for a week on a special train with Willy Brandt during his successful election campaign to become Germanys chancellor. I emerged from that train with a unique insight about politicians and statecraft. Not least, that every politician is best judged by his or her closest advisers. Thereafter I spent many years producing BBC TV documentaries in Germany (about the Allied failure to prosecute Nazi war criminals and to de-Nazify post-war Germany) and across the world. Witnessing a myriad of wars, elections, corrupt politicians and shady businessmen cured me of Marxism, but not of my curiosity and innate scepticism.