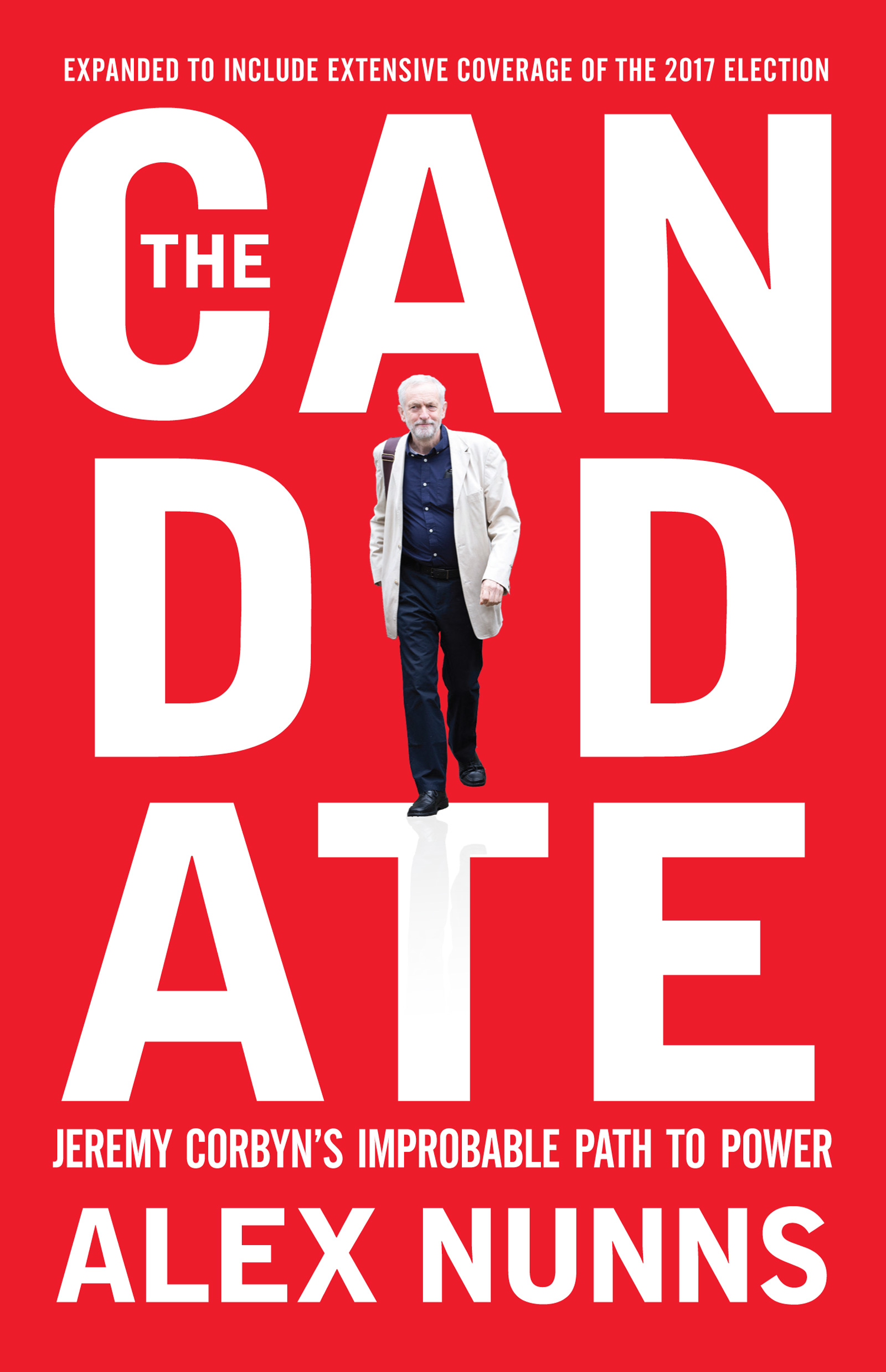

THE CANDIDATE

We all went into this thinking it was going to be the Charge of the Light Brigade.

Clive Lewis MP

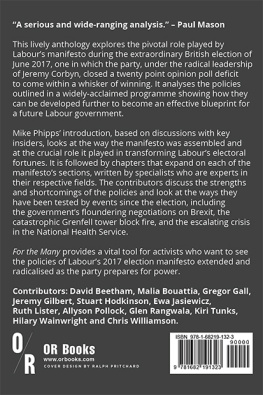

2018 Alex Nunns

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

All rights information:

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

First printing 2016

Second edition 2018

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-94486-961-8 paperback

ISBN 978-1-68219-105-7 e-book

Text design by Under|Over. Typeset by AarkMany Media, Chennai, India.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Politics isnt going back into the box where it was before.

Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Corbyn has a tiny television. In his house in Islington the Labour leader, his wife, and his closest aides have gathered for the release of the exit poll that will give the first indication of the result of the June 2017 general election. They have no idea what is coming; they will find out when they see it on TV like everyone else. But the television, sitting on a pile of books, is so small that Corbyn and his strategy chief Seumas Milne are forced to stand right in front of it, anxiously awaiting the news.

It is approaching 10 p.m., the moment of truth. Corbyn has given each of his companions a sheet of paper and asked them to predict Labours result. His chief of staff, Karie Murphy, is the most optimisticto the amusement of her colleagues she has been talking for weeks about what they will do when were in Number 10. The expectations of the others are lower, tempered by experience and by the Labour Partys internal polling, which points to a Tory landslide.

Merely the fact that there is doubt about the result counts as an achievement for the leadership, however. When the snap election was called on 18 April almost every political pundit had written off Labour. Theresa Mays gamble was about the surest bet any politician could ever place, wrote Jonathan Freedland in the Guardian . By that point Corbyn had been subjected to nearly two years of ridicule and distortion by the vast bulk of the media. He had been undermined and even bullied by his own MPs and other elements within his party. Opinion polls had suggested the Conservatives lead was as big as the entire Labour vote.

There followed one of the most remarkable election campaigns mounted by any party in British history. In the seven weeks of the contest, according to some polls, Labours standing has improved by up to 15 percentage points. But only the official exit poll will reveal if these projected gains have been real.

Big Ben strikes 10 p.m. All eyes are on the small screen. And what were saying is the Conservatives are the largest party, announces presenter David Dimbleby. Note they dont have an overall majority.

There is a sharp intake of breath.

Hung parliament! exclaims Milne.

Four hours later a throng of reporters and cameramen is waiting for Corbyn to arrive at the local sports hall where the count for his constituency is taking place. There has already been a false alarm: the media had rushed forward in response to cheers, only to find the hubbub was for the arrival of the Official Monster Raving Loony Party candidate. But the presence of armed police at the door signals that the entrance of the man of the moment is imminent.

A beaming Corbyn strides into the building to a burst of applause. Even some of the other parties join in. It is an acknowledgement of his remarkable, against-the-odds campaign performance. But it also reflects the dignified way in which he has carried himself throughout the election. As he pushes through the scrum of journalists wielding microphones and cameras, one reporter shouts out: Jeremy, are you the next prime minister? His status has grown immeasurably in just a few hours.

Once all the candidates for the seat of Islington North are assembled on stage, the returning officer reads out the numbers: 4,946 votes for the Liberal Democrat candidate; 6,871 for the Conservative. Then: Jeremy Bernard Corbyn, Labour Party, 40,086. A big cheer goes up. Corbyn raises his eyebrows in surprise, an involuntary smile on his face. It is a thumping result; he has taken 73 per cent of the vote. 10,000 more people have voted for him than in the previous general election.

Its an enormous honour to be elected to represent Islington North for the ninth time and Im very, very honoured and humbled by the size of the vote that has been cast for me as the Labour candidate, Corbyn says in his acceptance speech. Turning to the broader picture, he declares: Politics has changed. Politics isnt going back into the box where it was before People have said theyve had quite enough of austerity politics, theyve had quite enough of cuts in public expenditure and of not giving our young people the chance they deserve People are voting for hope.

Politics had changed. Despite not winning the June 2017 general election, Labour recorded an extraordinary result, experiencing its biggest jump in the popular vote since 1945 and adding seats to its tally in parliament for the first time since 1997. But the numbers reflected something more profound, if less tangible.

The election animated a new spirit. On the night before polling day, Jeremy Corbyn had returned to Islington for the final campaign rally of his marathon tour around the country. The event was being held inside the Union Chapel, but the most remarkable scenes occurred outside. Labours bright red battle bus crept towards the venue through streets packed with well-wishers. Thronging crowds spilled onto the road, blocking a major London thoroughfare. Some climbed trees and even lamp posts to welcome the Labour leader home. But perhaps more noteworthy were the reactions of less dedicated typesthose who came out of pubs with their drinks to join in a chorus of Oh Jeremy Corbyn, the spontaneous election anthem, or people on their way to the tube station who stopped to clap the arrival of the bus. The atmosphere was more like that of a music festival or a dramatic sports final than fuddy-duddy party politics.

This had been no ordinary election campaign. It had signalled a shift in political common sense. Millions of people, especially young people, were no longer satisfied by the narrow menu of options that had been offered up by the political elite for more than three decades. Such a development requires explanation. The story of how the ossified shell of British politics was cracked open goes back to an even more unlikely event two years earlier: the election of Corbyn as Labour leader. Both shock results were expressions of the same underlying phenomenon. The clues were there for those who wished to see them.

1

INTRODUCTION

Weve been through 100 days of the most amazing experience many of us have had in our lives.

Jeremy Corbyn

Wow, says John McDonnell, breaking the silence. Everyone in the room expected Jeremy Corbyn to win, but not by this much. The unelectable left-winger has just taken 59.5 per cent of the vote in a four-horse race.

The candidates and their campaign chiefs have been cooped up on the third floor of Westminsters vast Queen Elizabeth II conference centre for 40 minutes anxiously awaiting advance notice of the result. Deprived of their phones and iPads to prevent the news leaking out, they have been forced to make small talk. After a summer in which the contenders have whiled away countless hours backstage at hustings up and down the country, there is not much more to say. When the gruelling programme of events began, Corbyn was a 200/1 rank outsider. Today, 12 September 2015, he is about to become leader of the Labour Party.

Next page