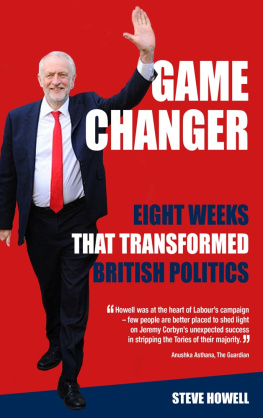

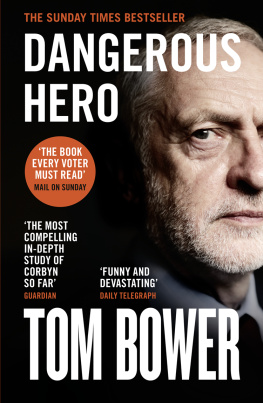

Game Changer

Eight Weeks That Transformed British Politics

Published by Accent Press Ltd 2018

www.accentpress.co.uk

Copyright Steve Howell 2018

The right of Steve Howell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this book, neither the author nor the publisher assumes responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretations of the subject matter herein.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of Accent Press Ltd.

ISBN 9781786155863

eISBN 9781786155870

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For those who died in the Grenfell Tower fire on Wednesday 14 June 2017 and for their families and those who survived, now fighting for justice.

There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolise. There is a failure here that topples all our success.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

1 The Day of Reckoning

Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute.

Shelley, The Masque of Anarchy

It was 9.50pm, Thursday June 8, 2017. In ten minutes, polls would close in one of the most dramatic and unpredictable general elections of modern times. Jeremy Corbyns tightly-knit communications team had assembled on the eighth floor at Southside, Labours head office near Victoria, ready for an all-night media operation. Supplies of biscuits, crisps and chocolate brownies were scattered across the large table we were gathered around. But most of it was untouched. No one was eating even for comfort as we waited for the exit poll. Would Theresa May get her landslide, as some polling companies were still predicting? Or did we dare to believe that Labour had closed the gap? Was it possible that we had come from so far behind to deny the Tories a parliamentary majority and possibly see Jeremy form a government?

Never before in a general election had there been so much variation in the polls. The final batch before Election Day differed by nearly 12 percentage points. Survation was saying the vote shares would be 41 per cent for the Tories and 40 per cent for Labour in polling terms, a dead heat. At the other end of spectrum, BMG Labours own agency was predicting a 46 per cent to 33 per cent Tory victory.

Meetings with BMG before and during the campaign had been grim. They were like a parallel world where all the energy and brightness we were seeing across the country was replaced by gloom and paralysing pessimism. The data was abundant, presented in one doom-laden slide after another, but it was completely at odds with the huge crowds turning out to hear Jeremy speak and the response we were getting on social media. But were we kidding ourselves? Were the rallies preaching to the converted, as some detractors claimed? Was social media an echo chamber or were the millions of views of our material winning hearts and minds? Younger voters were the nub of this conundrum. We knew we had a huge lead among people under 35, but had they registered in large enough numbers and would they turn out on the day?

What we did know was that we could increase the Labour vote substantially from the 30.4 per cent achieved under Ed Miliband in 2015 and yet still lose seats because of the way an expected collapse in the UKIP vote could boost the Tories in some Labour-held constituencies. In order to deny the Tories a majority, we would have to increase the Labour share of the vote to a level not seen since 1997, which some experts had ridiculed us for even thinking possible.

Conventional wisdom has it that you dont shift opinion in a general election campaign by more than two or three percentage points. The gap we had to close, based on the average of the polls immediately prior to May calling the election on April 18, was 16 points. In the first poll after that, YouGov had us a staggering 48 to 24 per cent behind. Even Survation, the pollster that ended up calling it correctly, had us trailing 40 to 29 per cent in its first poll on April 22.

Among those directing the campaign, everyone thought we had done well. But there were different views on how well. The formidable operational head of Jeremys office, Karie Murphy, would not hear talk of anything less than Labour forming a government. Early in the campaign, Jeremy, Jon Trickett, the shadow minister for the cabinet office, and Seumas Milne, the director of strategy and communications in the leaders office, had met the head of the civil service and cabinet secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood, for an initial briefing. With the polls narrowing, Jon, Karie, Seumas and Andrew Fisher, Jeremys policy director, met Sir Jeremy again a week before polling to discuss foreign visits and a possible legislative timetable in the event of Jeremy becoming prime minister. Then Karie and Andrew went back again in the final week to talk about Downing Street staffing and the details of what would happen on the day after the election if Labour was the largest party.

Until the final weekend before polling day, my expectations had been much the same as Karies. I had delayed a trip to California to see my son and his family so that I would be around to help if Jeremy was called upon to form a government. But the Tories had intensified their attacks on us, feeding smears to their friends in the national press and running a shockingly dishonest social media campaign. The day before polling, the Daily Mail ran a front page editorial under the headline Apologists for terror accusing Jeremy, John McDonnell and Diane Abbott of befriending Britains enemies. The Suns offering the same day was another spurious story headlined Jezzas Jihadi comrades. The Telegraph, Times and Express peddled similar attacks.

These slurs and slanders had been relentless throughout the campaign, but it was hard to tell if this final burst exploiting real and raw fears of terrorism after the Manchester and London Bridge attacks would sway some voters at the last minute. I had braced myself for this suppressing our vote, in the way the Sun claimed credit for doing in 1992 with its infamous front page: If Kinnock wins today, will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights.

Like it or not, our post-election planning had to straddle all the scenarios. We had sketched out several possibilities. At the top of the range was a Labour government and the implementation of the Downing Street organogram on Karies desk. At the other extreme was the possibility that the increase in the Labour vote would not be big enough to prevent the loss of some seats, possibly triggering calls for Jeremy to resign. In between there was a hung Parliament, a very narrow Tory majority and something close to the status quo in terms of seats. All our planning anticipated an increase in our vote the question was how big it would be.

As we waited for the exit poll that night, I was numb from exhaustion and beyond even thinking about the different scenarios. The eight weeks of the campaign had been relentless for everyone working inside the national machine. Labour staffers, temporary recruits, and the teams from Jeremy and John McDonnells offices about two hundred of us had spent just about every waking hour focusing on the most extraordinary election battle anyone, even those of us at the upper end of the age range, could remember.

At any one time, some of the communications and events staff would be out on the road, either with Jeremy or as part of the advance team, sent out to recce the next set of visits and rallies. The rest of us were packed into two floors of the characterless concrete and glass Southside building, living mostly on caffeine, adrenalin and far too much sugary stuff from the convenience store across the road.

Next page