ALSO BY ROBERT WILSON

Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation

The Explorer King: Adventure, Science, and the Great Diamond HoaxClarence King in the Old West

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2019 by Robert Wilson

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition August 2019

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information, or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Lewelin Polanco

Jacket design by Will Staehle

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wilson, Robert, 1951 February 21 author.

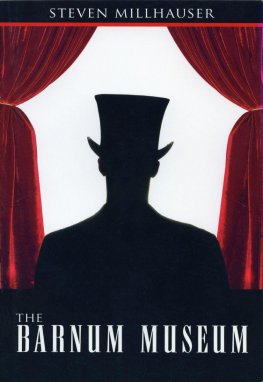

Title: Barnum : an American life / Robert Wilson.

Description: First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. | New York : Simon & Schuster, 2019. | Series: Simon & Schuster nonfiction original hardcover | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019000245| ISBN 9781501118623 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501118715 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781501118722 (ebook)

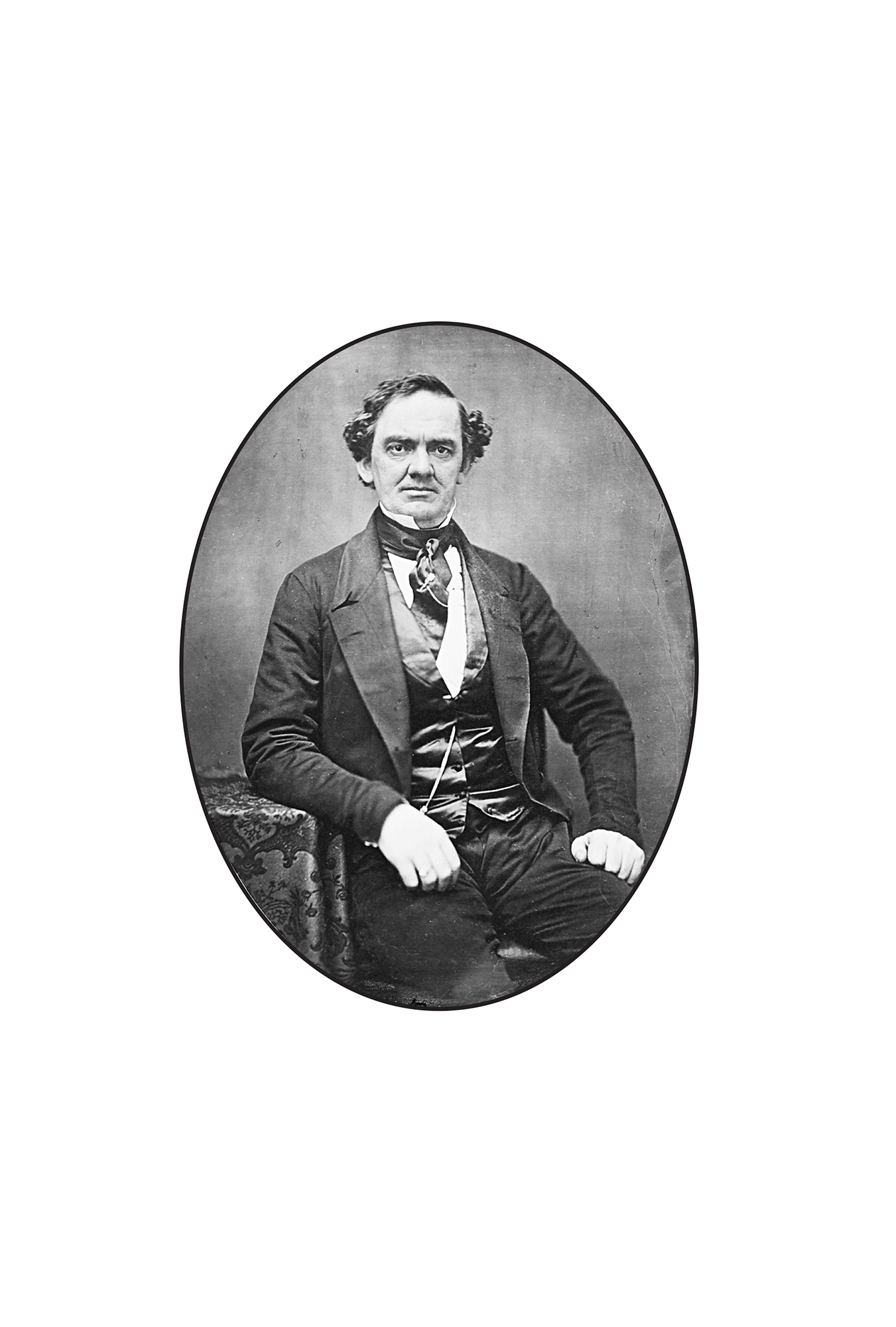

Subjects: LCSH: Barnum, P. T. (Phineas Taylor), 18101891. | Circus ownersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC GV1811.B3 W57 2019 | DDC 791.3092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019000245

ISBN 978-1-5011-1862-3

ISBN 978-1-5011-1872-2 (ebook)

For Martha

and for

Leyli Thea Wilson

and

Lawrence Ritchie Wilson

In Memory of

Mario Pellicciaro

INTRODUCTION

DO YOU KNOW BARNUM?

Adopting Mr. Emersons idea, I should say that Barnum is a representative man. He represents the enterprise and energy of his countrymen in the nineteenth century, as Washington represented their resistance to oppression in the century preceding.

John Delaware Lewis, Across the Atlantic , 1851

I n 1842, the man who would become Americas greatest showman received a visit from a museum owner in Boston who needed his help. Moses Kimball had made his way to P. T. Barnums office in New York City with a box that, he baldly claimed, contained the remains of a mermaid. When the box was opened and the object was unwrapped, what Barnum saw was a shrunken, blackish thing about three feet long that seemed pretty obviously to be the head and torso of a monkey joined to the lower portion of a large fish. Kimball had a story to go with this desiccated corpse, something about its being discovered by sailors in the South Seas, but he had no idea what to do with it. Although the two men had not previously met, their establishments had collaborated on several acts and exhibitions. Barnum had recently acquired a dusty old museum on lower Broadway, dubbed it the American Museum, and dedicated it to natural history, art and artifacts,

While Kimball wondered what could be done with this grotesque specimenso different from the beautiful mythological beings that people had imagined for centuriesBarnum didnt hesitate. He offered to lease the object from Kimball and present it to the public himself. After giving the creature an exotic namethe Fejee Mermaidhe created a bold strategy to conjure up a storm of interest in it.

Within days Barnum was executing a complicated plan to acquire free publicity from the press. He sent letters to friends in cities in the South, all telling a made-up story about a British naturalist who had acquired the mermaid in the Fiji Islands and was stopping in New York on his way to London, where it would be put on display. This naturalist was supposedly passing through the South, and every few days a friend from a different southern city would mail one of Barnums letters, which were written as news reports of local happenings, to a different New York newspaper. While he was whetting the appetite of the press, Barnum had posters made of beautiful, bare-breasted mermaids with long blond curls, implying that this was what the Fejee Mermaid had once looked like. By the time the supposed naturalist reached New York, the press was in a frenzy, and Barnum gave three different newspapers an unsigned report that he had written defending the existence of mermaids, along with an idealized image in woodcut, suitable for printing. Each of the newspapers was promised an exclusive, and it was only when all three published the story on the same Sunday morning that they knew they had been hoodwinked. If the editors were miffed, they didnt show it by withholding coverage of the exhibit. After all, Barnum was a steady advertiser, and this new exhibit would mean new ads each day in their newspapers.

Its safe to say that most people who came to see the Fejee Mermaid and hear the ersatz naturalist talk about it were not taken in. But Barnums early publicity drew huge crowds to the display, and even if they doubted that this shriveled specimen had ever been the lovely, storied creature in the posters, still it was a thing worth seeing and judging for themselves. Whatever the skepticism of his patrons, the showman didnt let up in the weeks that followed. With a steady stream of ads, often warning that the display would soon be leaving for London, augmented by a barrage of pamphlets and posters, he kept the customers coming. When the flow of visitors finally slowed, he sent the Fejee Mermaid out on the road. His plan, which had come to him in an instant when he first saw the specimen, had worked to perfection.

Later in life, Barnum would confess that he was not proud of this exhibit, but even then he could not resist exulting in the success of his publicity scheme. The Fejee Mermaid was characteristic of Barnums exhibitions during his early years; even as a young man he had an unfailing sense of what the public wanted, yet he could be brazenly manipulative and unafraid of controversy. These qualities made him successful as a showman, but they also made it possible for him to push too far. When, for instance, he had put on tour an elderly slave woman who claimed to be the 161-year-old former nursemaid to George Washington, the newspapers and other guardians of public virtue howled, condemning him for exploiting her. At other times, Barnum drew criticism less for his actions than for his attitude. When he published the first version of his autobiography, in 1855, detailing his many humbugs and the riches they had afforded him, some reviewers were disgusted not so much by the original sins but by his seeming pride in admitting to them. He was often seen as a man who would do anything for a buck, and by the time he was middle-aged, the quip Wheres Barnum? was applied to any novelty, discovery, or invention of the day, under the assumption that he would soon show up to add it to his museum collection.

The missteps of Barnums early career would ultimately damage his reputation in a lasting way. Well after his death in 1891, his image in the public mind congealed around another phrase, this one attributed to Barnum himself: Theres a sucker born every minute. The cynical saying implies that he was no better than a huckster, whose chief goal was using fast talk to trick people out of their money while giving them nothing in return. Even to this day, these words serve as shorthand for Barnums philosophy as a showman, but no evidence exists that he ever spoke or wrote them. Whats worse, they utterly misrepresent the man as he really was.

Next page